Arunachal Tawang residents protest against unfulfilled promises Hundreds of residents on July 22 marched through the streets of Tawang, the home district of newly elected CM Pema Khandu, in protest against non-fulfillment of their demand for jobs to kith and kins of two anti-dam activists killed in police firing on May 2. During the protest march they also led a signature campaign against large dams planned in Tawang, where the predominantly Buddhist Monpa tribe feared that many of the proposed hydro-power projects would damage sacred Buddhist sites in the district. At least 13 large hydro-power projects have been planned in the district, which shares border with China’s Tibet region. On June 21 the Lamas-led Save Mon Region Federation had issued six-point charter of demand to the state government for fulfillment in 30 days. Arunachal comprises a fragile, rich parcel of wildlife and ecosystem, among the richest ecosystems in India. But planning & building of hydro projects has been and will cause irreversible environmental damage. Perhaps it’s time for an aggressive freeze on all the un-built projects and an evaluation of other models of energy. Mr Prema Khandu must consider why Arunachal should become India’s mitochondria-the country’s energy provider, while losing its own enormous wealth. But contrary to this new while addressing a press conference, the new CM, on July 18 said that the govt would find ways to tap the petroleum resources & harness the hydropower potential which could be a money spinner for the state. On the 2000Mw Lower Subanisiri HEP at Gerukamukh, Mr Khandu has emphatically said he would discuss the issue with the Assam govt as well as the Centre for a solution. He said that in all the hydropower projects the affected people should be taken into confidence by both the executing agencies as well as the state govt. The new CM elected from Tawang, seeing the hydropower projects as money spinner does not sound very encouraging. Let us see how far he actually goes to take people into confidence as promised by him.

Tag: brahmaputra

Bhatiyali: The Eternal Song of the River

ओ रे माँझी, ओ रे माँझी

मेरे साजन हैं उस पार, मैं मन मार , हूँ इस पार

ओ मेरे माँझी अब की बार ले चल पार, ले चल पार

Everything about this song: its words, its music, its picturisation and Sachin Deo (SD) Burman’s evocative voice mesmerizes me (I’m one of many others, I’m sure). I loved this song’s connect with rivers and used to repeat it over and over, till my (visibly exasperated) husband told me, “But did you not know? Rivers have influenced SD’s music a lot. He has talked about his lone ramblings on the Gumti in Tripura, listening to folk music based on rivers many times”. I did not know that. Continue reading “Bhatiyali: The Eternal Song of the River”

Rivers in the News during 2014

Above: The beautiful Lohit River, Arunachal Pradesh Photo: Arati Kumar Rao (http://riverdiaries.tumblr.com/)

Know our rivers: A beginners guide to river classification

Who has not seen a river? And who has then, not been moved by a fierce emotion? The common man sees its life granting blessed form, the government or CWC engineer sees in it as a potential dam project, the hydropower developers a site for hydro project, a farmer his crop vitality, fisher folk, boatspeople and river bed cultivators a source of livelihood, the industry & urban water utilities view it as their personal waste basket, the real estate developer as a potential land grab site, a sand miner as a source of sand and the distraught villager his lifeline. In earlier days, film makers used to see it as site for filming some memorable songs, but these days even that has become a rarity.[1]

Rivers truly are a complex entity that invoke varied emotions and responses!

A river shifts in colour, shape, size, flow pattern of water, silt, nutrients and biota, in fact all its variables seem to change with time and space. The perceptions differ as one moves from mountains to plains to the deltas. The same stream displays a wide variance of characteristics that depend upon the land it flows through and the micro climate along its banks. Rivers many a times seem to mirror the local flavour of the land they flow through. Or is it the local flavour that changes with river flow? Clearly both are interdependent.

Today, as we talk of rivers, their rejuvenation and try to figure out their ecological flow and their health quotient , a good beginning to understand the existing rivers would be their classification modules. What defines a river? Which factors are used for their classification? How do we actually classify our rivers?

As far as the first of these questions is concerned, none of the official agencies have tried to define a river!

Possiby, the first post independence classification of river basins was attempted in 1949 by precuser institute of current Central Water Commission (CWC). Since then various organisations have followed their own methodology and criteria for basin classification and arrived at different numbers.

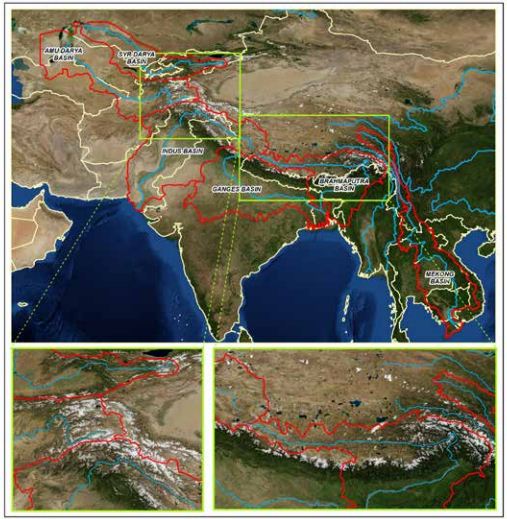

NIH (National Institute of Hydrology), Roorkee organises our 7 major rivers, that is the Brahmaputra (apparently this includes the Ganga and the Meghna), Godavri, Krishna & Mahanadi (that flow into the Bay of Bengal), and the Indus, Narmada & Tapi (which drain into the Arabian Sea) , along with their tributaries to make up the entire river system in our country.[2] This is clearly problematic and chaotic, since it leaves out vast areas of the country and the rivers that flow through them.

A quick look at the classification based on these 3 aspects –origin, topography and the basin they form.

- Based on Origin or Source

Depending on the origin or where they begin their journey from, there are the Himalayan (perennial) rivers that rise from the Himalayas and the Peninsular rivers that originate from the Indian plateau. The Himalayan rivers include the Ganga, the Indus and the Brahmaputra river systems along with their tributaries, which are fed throughout the year by melting ice and rainfall. They are swift, have great erosion capacity and carry huge amounts of silt & sand. They meander along the flat land, create large fertile flood plains in their wake and their banks are dotted by major towns and cities.

The peninsular rivers, on the other hand are more or less dependent on rain. These are gentler in their flow, follow a relatively straighter path, have comparatively less gradient and include Narmada, Tapi, Godavari, Krishna, Cauveri and Mahanadi rivers, among many others.

- Based on topography

The Himalayan Rivers flow throughout the year, are prone to flooding and include Indus and the Ganga-Brahmaputra-Meghna.

The Deccan Rivers include the Narmada and Tapi rivers that flow westwards into the Arabian Sea, and the Brahmani, Mahanadi, Godavari, Krishna, Pennar & Cauvery that fall into the Bay of Bengal.

The Coastal Rivers are comparatively small in size and numerous in number, with nearly 600 flowing on the west coast itself.

Rivers of the Inland Drainage Basin are centered in western Rajasthan, parts of Kutch in Gujarat and mostly disappear before they reach the sea as the rainfall here is scarce. Some of them drain into salt lakes or simply get lost in the vast desert sands.

Island Rivers Rivers of our islands: A&N islands & Lakshadip group of islands

- Based on basin formed

On the basis of the basin formed, our rivers are distributed into 7 river systems. The Indus River System originates in Kailash range in Tibet, and includes Zanskar, Shyok, Nubra ,Hunza (in Kashmir) along with Jhelum, Chenab, Ravi, Beas and Sutlej as its principal tributaries. In the Brahmaputra River System, it was earlier assumed that the Mansarovar lake is the source of the Brahmaputra river, however, now it is confirmed that Angsi Glacier is the main source (see: See: http://www.thehindu.com/news/international/china-maps-brahmaputra-indus/article2384885.ece). Most of the course of the river lies outside the country. In India it flows through Arunachal Pradesh and Assam, where it is joined by several tributaries. For more information on this river, see: https://sandrp.wordpress.com/2013/07/17/brahmaputra-the-beautiful-river-or-the-battleground/.

The Narmada River System comprises of the Narmada River that represents the traditional boundary between North & South India and which empties into the Arabian Sea in Bharuch district of Gujarat. Tapi river of the Tapi River System rises in the eastern Satpura Range of Madhya Pradesh and then empties into the Gulf of Cambay of the Arabian Sea, Gujarat. Its major tributaries are Purna, Girna , Panzara , Waghur , Bori and Aner rivers.

Also called the Vriddh (Old) Ganga or the Dakshin (South) Ganga, Godavari of the Godavari River System, originates at Trambakeshwar, Maharashtra and empties into the Bay of Bengal. Summers find the river dry, while monsoons widen the river course. Its major tributaries include Indravati, Pranahita, Manjira, Bindusara and Sabari rivers.

The Krishna River System includes Krishna river, one of the longest rivers of the country,that originates at Mahabaleswar, Maharashtra, and meets the sea in the Bay of Bengal at Hamasaladeevi, Andhra Pradesh. Tungabhadra River, formed by Tunga and Bhadra rivers, is one of its principal tributary. Others are Koyna, Bhima, Mallaprabha, Ghataprabha, Yerla, Warna, Dindi, Musi and Dudhganga rivers.

The Kaveri River System has the Kaveri (or Cauvery) river whose source is Talakaveri in the Western Ghats and it flows into the Bay of Bengal. It has many tributaries including Shimsha, Hemavati, Arkavathy, Kapila, Honnuhole, Lakshmana Tirtha, Kabini, Lokapavani, Bhavani, Noyyal and Amaravati. The Mahanadi of the Mahanadi River System, a river of eastern India rises in the Satpura Range and flows east into the Bay of Bengal.

Broader definition: Catchment area size

River basins are widely recognized as a practical hydrological unit. And these can also be grouped, based on the size of their catchment areas (CA). This easy to understand river system classification divides them into the following categories as tabulated below:

| River basin | CA in sq km | No. of river basins | CA in million sq. Km | % area | % Run off | % population |

| Major river basin | CA > 20,000 | 14 | 2.58 | 83 | 85 | 80 |

| Medium | 20,000<CA<2,000 | 44 | 0.24 | 8 | 7 | 20 |

| Minor (Coastal areas) | CA< 2,000 | Many | 0.20 | 9 | 8 | |

| Desert rivers | Flow is uncertain & most lost in desert | – | 0.1 | – |

Major river basins include the perennial Himalayan rivers- Indus, Ganga & Brahmaputra, the 7 river systems of central India, the Sabarmati, the Mahi, Narmada & Tapi on the west coast and the Subarnekha, Brahmani & the Mahanadi on the east coast and the 4 river basins of Godavri, Krishna, Pennar and Cauvery, which takes the total to 14. The medium river basins include 23 east flowing rivers such as Baitarni, Matai & Palar. A few important west flowing rivers are Shetrunji, Bhadra, Vaitarna & Kalinadi. The minor river basins include the numerous, but essentially small streams that flow in the coastal areas. In the East coast, the land width between the sea and the mountains is about 100 km, while in the West coast, it ranges between 10 to 40 km. The desert rivers flow for a distance and then disappear in the desert of Rajasthan or Rann of Kutch, generally without meeting the sea.[3]

A need for details

Under India-WRIS (Water Resources Information System) project too, the river basin has been taken as the basic hydrological unit, but the country has been divided into 6 water resource regions, 25 basins and 101 sub basins, which are an extension of the earlier 20 basins delineated by CWC, as detailed in the ‘River basin Atlas of India’. [4] The details of the individual catchment area of these 20 river basins is tabulated here:

| S No | River Basin | CA (Sq. Km) | Major river | River Length, km |

| 1 | Indus (Upto border) | 321289 | Indus(India) | 1114 |

| 2 | Ganga- Brahmaputra-Meghna | |||

| a | Ganga | 861452 | Ganga | 2525 |

| b | Brahmaputra | 194413 | Brahmaputra (India) | 916 |

| c | Barak & others | 41723 | Barak | 564 |

| 3 | Godavari | 312812 | Godavari | 1465 |

| 4 | Krishna | 258948 | Krishna | 1400 |

| 5 | Cauvery | 81155 | Cauvery | 800 |

| 6 | Subernarekha | 29169 | Subernarekha | 395 |

| Burhabalang | 164 | |||

| 7 | Brahmani & Baitarni | 51822 | Brahmani | 799 |

| Baitarni | 355 | |||

| 8 | Mahanadi | 141589 | Mahanadi | 851 |

| 9 | Pennar | 55213 | Pennar | 597 |

| 10 | Mahi | 34842 | Mahi | 583 |

| 11 | Sabarmati | 21674 | Sabarmati | 371 |

| 12 | Narmada | 98796 | Narmada | 1312 |

| 13 | Tapi | 65145 | Tapi | 724 |

| 14 | West flowing rivers from Tapi to Tadri | 55940 | Many independent rivers | |

| 15 | West flowing rivers from Tadri to Kanyakumari | 56177 | ||

| 16 | East flowing rivers Between Mahanadi & pennar | 86643 | ||

| 17 | East flowing rivers Between Pennar & Kanyakumari | 100139 | ||

| 18 | W flowing rivers of Kutch & Saurashtra includes Luni | 321851 | Luni | 511 |

| 19 | Area of inland drainage in Rajasthan | 60269 | Many independent rivers | |

| 20 | Minor rivers draining into Myanmar & Bangladesh | 36202 | Many independent rivers | |

Note: 1. River Length is only for the main stem of the river, does not include tributaries, etc.

- Area of inland drainage in Rajasthan is not given in this reference, it has been arrived at by inference.

- Indus basin is constibuted by six main rivers: Sutlej, Beas, Ravi, Chenab, Jhelum and Indus itself. Some tributaries of this system form independent catchment in India (e.g. Tawi river in Chenab basin) as these confluence with the main river only in downstream of the border.

Of course these methods only classify rivers based on their physical & geographical attributes, their drainage area, river length, volume of water carried and tributary details. For a detailed study of a river, what is also needed is its ecological assessment. The methods for river classification may be varied and still evolving, but this information is fundamental to better understand and map the rivers that criss cross across the country.

And definitely a first step to try and understand our rivers!

Sabita Kaushal, SANDRP (sabikaushal06@gmail.com)

END NOTES:

[1] This blog is part of a series of blogs we plan to put up in view of the India Rivers Week being held during Nov 24-27, 2014, see for details: https://sandrp.wordpress.com/2014/10/15/press-release-india-rivers-week-from-24-27-nov-2014-first-irw-event-to-be-held-in-delhi/

[2] Rivers of India: National Institute of Hydrology, Roorkee

http://www.nih.ernet.in/rbis/india_information/rivers.htm#Peninsular

[3] India’s Water Wealth: KL Rao, Orient Longman, 1975

[4] River basin atlas of India, 2012: A report by Central Water Commission and Indian Space Research Organisation: http://www.indiawaterportal.org/articles/river-basin-atlas-india-report-central-water-commission-and-indian-space-research

Himalayas cannot take this Hydro onslaught

MESSAGE ON WORLD ENVIRONMENT DAY 2014:

SAVE HIMALAYAS FROM THIS HYDRO ONSLAUGHT!

It is close to a year after the worst ever Himalayan flood disaster that Uttarakhand or possibly the entire Indian Himalayas experienced in June 2013[1]. While there is no doubt that the trigger for this disaster was the untimely and unseasonal rain, the way in which this rain translated into a massive disaster had a lot to do with how we have been treating the Himalayas in recent years and today. It’s a pity that we still do not have a comprehensive report of this biggest tragedy to tell us what happened during this period, who played what role and what lessons we can learn from this experience.

One of the relatively positive steps in the aftermath of the disaster came from the Supreme Court of India, when on Aug 13, 2013, a bench of the apex court directed Union Ministry of Environment and Forests (MoEF)[2] to set up a committee to investigate into the role of under-construction and completed hydropower projects. One would have expected our regulatory system to automatically initiate such investigations, which alas is not the case. Knowing this, some us wrote to MoEF on July 20, 2013[3], to exactly do such an investigation, but again MoEF played deaf and blind to such letters.

The SC mandated committee was set up through an MoEF order dated Oct 16 2013[4] and MoEF submitted the report on April 16, 2014.

The committee report, signed by 11 members[5], makes it clear that construction and operation of hydropower projects played a significant role in the disaster. The committee has made detailed recommendations, which includes recommendation to drop at least 23 hydropower projects, to change parameters of some others. The committee also recommended how the post disaster rehabilitation should happen, today we have no policy or regulation about it. While the Supreme Court of India is looking into the recommendations of the committee, the MoEF, instead of setting up a credible body to ensure timely and proper implementation of recommendations of the committee has asked the Court to appoint another committee on the flimsy ground that CWC-CEA have submitted a separate report advocating more hydropower projects! The functioning of the MoEF continues to strengthen the impression that it is working like a lobby for projects rather than an independent environmental regulator. We hope the apex court see through this.

Let us turn our attention to hydropower projects in Himalayas[6]. Indian Himalayas (Himachal Pradesh, Uttarakhand[7], Jammu & Kashmir, Sikkim, Arunachal Pradesh and rest of North East) already has operating large hydropower capacity of 17561 MW. This capacity has leaped by 68% in last decade, the growth rate of National Hydro capacity was much lower at 40%. If you look at Central Electricity Authority’s (CEA is Government of India’s premier technical organisation in power sector) list of under construction hydropower projects in India, you will find that 90% of projects and 95% of under construction capacity is from the Himalayan region. Already 14210 MW hydropower capacity is under construction. In fact CEA has now planned to add unbelievable 65000 MW capacity in 10 years (2017 to 2027) between 13th and 14th Five Year Plans.

Meanwhile, the Expert Appraisal Committee of Union Ministry of Environment and Forests on River Valley Projects has been clearing projects at a break-neck speed with almost zero rejection rate. Between April 2007 and Dec 2013[8], this committee recommended final environment clearance to 18030.5 MW capacity, most of which has not entered the implementation stage. Moreover, this committee has recommended 1st stage Environment clearance (what is technically called Terms of Reference Clearance) for a capacity of unimaginable 57702 MW in the same period. This is indicative of the onslaught of hydropower projects which we are likely to see in the coming years. Here again an overwhelming majority of these cleared projects are in Himalayan region.

Source: SANDRP

What does all this mean for the Himalayas, the people, the rivers, the forests, the biodiversity rich area? We have not even fully studied the biodiversity of the area. The Himalayas is also very landslide prone, flood prone, geologically fragile and seismically active area. It is also the water tower of much of India (& Asia). We could be putting that water security also at risk, increasing the flood risks for the plains. The Uttarakhand disaster and changing climate have added new unknowns to this equation.

We all know how poor are our project-specific and river basin-wise cumulative social and environmental impact assessments. We know how compromised and flawed our appraisals and regulations are. We know how non-existent is our compliance system. The increasing judicial interventions are indicators of these failures. But court orders cannot replace institutions or make our governance more democratic or accountable. The polity needs to fundamentally change, and we are still far away from that change.

The government that is likely to take over post 2014 parliamentary elections has an opportunity to start afresh, but available indicators do not provide such hope. While UPA’s failure is visible in what happened before, during and after the Uttarakhand disaster, the main political opposition that is predicted to take over has not shown any different approach. In fact NDA’s prime ministerial candidate has said that North East India is the heaven for hydropower development. He seems to have no idea about the brewing anger over such projects in Assam and other North Eastern states. That anger is manifest most clearly in the fact that India’s largest capacity under-construction hydropower project, namely the 2000 MW Lower Subansiri HEP has remained stalled for the last 29 months after spending over Rs 5000 crores. The NDA’s PM candidate also has Inter Linking of Rivers (ILR) on agenda. Perhaps we have forgotten as to why the NDA lost the 2004 Parliamentary elections. The arrogant and mindless pursuit of projects like ILR and launching of 50 000 MW hydropower campaign by the then NDA government had played a role in sowing the seeds of people’s anger with that government.

In this context we also need to understand what benefits these hydropower projects are actually providing, as against what the promises and propaganda are telling us. In fact our analysis shows that the benefits are far below the claims and impacts and costs are far higher than the projections. The disaster shows that hydropower projects are also at huge risk in these regions. Due to the June 2013 flood disaster large no of hydropower projects were damaged and generation from the large hydro projects alone dropped by 3730 million units. In monetary terms this would mean just the generation loss at Rs 1119 crores assuming conservative tariff of Rs 3 per unit. The loss in subsequent year and from small hydro would be additional.

It is nobody’s case that no hydropower projects be built in Himalayas or that no roads, townships, tourism and other infrastructure be built in the Himalayan states. But we need to study the impact of these massive interventions (along with all other available options in a participatory way) in what is already a hugely vulnerable area, made worse by what we have done so far in these regions and what climate change is threatening to unleash. In such a situation, such onslaught of hydropower projects on Himalayas is likely to be an invitation to even greater disasters across the Himalayas. Himalayas cannot sustain this onslaught.

It is in this context, that the ongoing Supreme Court case on Uttarakhand provides a glimmer of hope. It is not just hydropower projects or other infrastructure projects in Uttarakhand, or for that matter in other Himalayan states that will need to take guidance from the outcome of this case, but it could provide guidance for all kinds of interventions all across Indian Himalayas. Our Himalayan neighbors can also learn from this process. Let us end on that hopeful note here!

Himanshu Thakkar (ht.sandrp@gmail.com)

END NOTES:

[1] For SANDRP blogs on Uttarakhand disaster of June 2013, see: https://sandrp.wordpress.com/?s=Uttarakhand

[2] For details of Supreme Court order, see: https://sandrp.wordpress.com/2013/08/14/uttarakhand-flood-disaster-supreme-courts-directions-on-uttarakhand-hydropower-projects/

[3] https://sandrp.wordpress.com/2013/07/20/uttarakhand-disaster-moef-should-suspect-clearances-to-hydropower-projects-and-institute-enquiry-in-the-role-of-heps/

[4] For Details of MoEF order, see: https://sandrp.wordpress.com/2013/10/20/expert-committee-following-sc-order-of-13-aug-13-on-uttarakhand-needs-full-mandate-and-trimming-down/

[5] https://sandrp.wordpress.com/2014/04/29/report-of-expert-committee-on-uttarakhand-flood-disaster-role-of-heps-welcome-recommendations/

[6] https://sandrp.wordpress.com/2014/05/06/massive-hydropower-capacity-being-developed-by-india-himalayas-cannot-take-this-onslought/

[7] https://sandrp.wordpress.com/2013/07/10/uttarakhand-existing-under-construction-and-proposed-hydropower-projects-how-do-they-add-to-the-disaster-potential-in-uttarakhand/

[8] For details of projects cleared during April 2007 to Dec 2012, see: https://sandrp.in/env_governance/TOR_and_EC_Clearance_status_all_India_Overview_Feb2013.pdf and https://sandrp.in/env_governance/EAC_meetings_Decisions_All_India_Apr_2007_to_Dec_2012.pdf

[9] An edited version of this published in June 2014 issue of CIVIL SOCIETY: http://www.civilsocietyonline.com/pages/Details.aspx?551

Matmora (Assam) Geo-tube Embankment on Brahmaputra: State Glorifies, but No End to Peoples’ Sufferings after Three Years of Construction

The state of Assam in the northeastern India annually bears the brunt of floods and where embankment construction and repairing seems like permanent affair. Displacement of people living on the banks of rivers due to river bank erosion is another major issue here. The braiding and meandering river Brahmaputra and its tributaries continue to erode the banks rapidly. The Brahmaputra is well known for the rate in which it erodes. Among the places in the path of the river where the brunt of erosion has been felt severely include the following:

– Rohmoria and Dibrugarh town in Dibrugarh district,

– Matmora in Dhakukhana subdivsion of Lakhimpur district,

– Majuli and Nimati Ghat in Jorhat district,

– Lahorighat in Morigaon district and

– Palashbari and Gumi in Kamrup district.

SANDRP recently traveled to Matmora and Nimati ghat, two of these areas.

Bearing the Brunt of Erosion Silently Once a large village now only the name Matmora remains. Locals show us towards the middle of the river, to indicate where the village used to be. The rate of erosion is such that the Brahmaputra dyke from Sissikalghar to Tekeliphuta (popularly known as Sissi-Tekeliphuta dyke/embankment) takes the shape of a bow for nearly five kilometers at this place. From 2010, Matmora became very significant in the embankment history of India since country’s first embankment using geo-textile technology was constructed here. This was constructed at the bow shaped eroded line using geotextiles tubes. These tubes were filled up using water and sand from the banks of the river. This five kilometer embankment became a part of the Brahmaputra dyke from Sissikalghar to Tekeliphuta which is 13.9 km long. For the state government and Water Resources Department (WRD) of Assam, Matmora geotube embankment is a story of success of preventing floods and erosion. But what we saw in Matmora presents a different picture.

At Nimati Ghat, the river Brahmaputra is eroding its banks ferociously and people are intimidated by the river. A local person whose village used to be nearly two kilometers from the present bank line, told me, “Nothing can stop Baba Brahmaputra from claiming what he wants”. At Nimati Ghat, the Water Resources Department (WRD) is doing anti erosion work using geo-bags.

Funding for Embankments in Assam The total length of embankments in Assam is 4448 km as stated in a debate in the Legislative Assembly of Assam in 1998. Even though the present length of embankments is not known, it is very clear that the state of Assam continues to construct of newer embankments. In a recent analysis by SANDRP, it was found that the funds continue to increase for construction of embankments in the state. In five years from January 2009 to December 2013, the Advisory Committee in the Union Ministry of Water Resources for consideration of techno-economic viability of Irrigation, Flood Control and Multi-Purpose Project Proposals (TAC in short) had given clearance to projects worth Rs 1762.72 crores. A detailed list of these sanctioned projects can be found in Annexure 1 below.

Has Geo-tube been helpful for the people Between January 2009 to December 2013, the Brahmaputra dyke from Sissikalghar to Tekeliphuta, was considered twice by the TAC. The committee in its 95th meeting on 20th January 2009 accepted the project titled “Raising and Strengthening to Brahmaputra dyke from Sissikalghar to Tekeliphuta including closing of breach by retirement and anti-erosion measures (to protect Majuli and Dhakukhana areas against flood devastation by the Brahmaputra, Lakhimpur district, Assam). The estimated cost of this project was Rs 142.42 crore and its project proposal envisaged – (i) Raising and strengthening of embankment for a length of 13.9 km, (ii) Construction of retirement bund with geo-textile tubes of length 5000 m. (iii) Construction of 2700 m long pilot channel.

Protection work of the same dyke was considered in the 117th meeting held on 21st March 2013 under the proposal for “Protection of Brahmaputra dyke from Sissikalghar to Tekeliphuta at different reaches from Lotasur to Tekeliphuta from the erosion of river Brahmaputra Assam.” The estimated cost of this project was Rs 155.87 crore. According to the minutes of 117th TAC meeting, the scheme envisaged “restoration of existing embankment in a length of 15300m at upstream and downstream of existing geo-tube dyke, Sand filled mattress in a length of 15604 m at river side slope, geo-tube apron length of 7204 m and Reinforced concrete porcupines as pro-siltation device at different reaches to prevent floods and erosion in Dhakukhana Civil sub-division of Lakhimpur district and Majuli sub-division of Jorhat district.” In the same minutes,while referring to the previous project proposal of 95th meeting the minutes stated that, it “was taken up primarily for closure of breach in the existing embankment including raising of embankment around the breach area only. The proposed works in the present scheme were in the same river reach and these would be required to protect the bank from further erosion and provide flood protection.”

This clearly shows that the geo-tube embankment in Matmora cannot be called a success. Government documents which showed that major part of the Brahmaputra dyke from Sissikalghar to Tekeliphuta remained vulnerable even after the construction of the geo-tube embankment. In fact submitting a proposal for the whole Sissi-Tekeliphuta embankment at first and later saying that the money was spent in constructing a smaller part of the embankment also raise questions. The time gap between the two proposals also raises questions. If the whole money from first proposal was to be spent in constructing only a part of the embankment, why was it not stated clearly in the first proposal? In fact, this was not stated in the first proposal and second proposal reflects that the first project failed to achieve the objectives. If the first proposal was indeed only for part of the embankment, why the proposal to strengthen the larger part of the embankment took 5 years to appear before the committee? The latter proposal also did not mention about the breach which swept away a large part of the Sissi-Tekeliphuta embankment from Jonmichuk to Amgiri Tapit under Sissikalghar and Jorkata village panchayat. According to the local people this breach occurred in the morning hours of 25th June 2012. The photo below shows the breach happened at the Jonmichuk end.

Jonminchuk area is nearly 15 km upstream of the geotube embankment in Matmora and part of the Sissi-Tekeliphuta embankment. A new embankment of nearly four kilometer long is being constructed at this place but the remnants of the old embankment still exist. The embankment was breached for nearly 3 kms and the water which entered the fields during that time could no longer go out and a large lake has been formed at this place, see the photo. It was surprising to see people living in the patches of the old embankment.

In the downstream, right from the point where the geo-tube embankment ends, the condition of the Sissi-Tekeliphuta embankment is pathetic. There were cracks in the embankment and water seepage has almost shattered the embankment. The embankment was in need of urgent repairs.

Besides, one does not have to travel far to find erosion in the downstream of the geo-tube embankment. After travelling, less than three kilometers from the end point of the geo-tube embankment, rapid erosion was observed at the place where the Matmora and Tekeliphuta ghats join, due to low water level. This joint ghat is more than a kilometer from the toe line of Sissi-Tekeliphuta embankment but seeing the rapidity of the erosion the locals opine that the river would reach the toe of the embankment within this monsoon. It was difficult to believe that the river can erode so fast, until a young man pointed towards a black line in the middle of the river and said that that area which now seemed to be char/sand bar used to be his village three years back. He with his family now live beside the embankment. In this ghat we also witnessed that spurs constructed from the embankment inside the river, mainly to divert the flow of water, have been eroded as well.

It is also important to note that protection of Majuli from floods was one of the main aims of the geo-tube embankment project, but there were reports of devastating floods affecting Majuli in 2012 & 2013.

After geo-tube comes geo bags With the construction of geo-tube embankments being hailed as a success by the state government, construction of embankments using geo-bags followed. Geo-bags are smaller than geo-tubes and come at a cheaper cost. Embankments on many rivers were constructed using geo-bags which were also used for erosion protection. But effectiveness of the geo-bags as protective measure to flood and erosion, still remains disputed. A news report titled “ADB, river engineers differ on geo-bags” published in Assam Tribune on 9th September 2010 reported about the difference of opinion among the water resource engineers of Assam and powerful lobby of the Asian Development Bank (ADB) for the use of geo-bags to resist Brahmaputra erosion in Palasbari-Gumi and Dibrugarh. Referring to the engineers the news report stated “They have alleged that the ADB provided 23,000 geo-bags for an experiment. They were dumped in the month of September 2009 at a 150-metre-long selected erosion-prone reach at Gumi for testing their efficacy. But, a diving observation made in the month of December 2009, suggested that the bags were not launched uniformly in a single layer as it was claimed. They were found lying in a haphazard manner in staggered heaps with gaps in between and the total distance they covered was only about 8 metres, against the claimed and required 35 metres…..The ADB then carried out another diving observation at Gumi in May last (2010) and found no bag at the site. The State WRD did not get any feedback from the ADB on this issue.”

Nimati Ghat was the other place which SANDRP visited to find out the effectiveness of geo-bags. The work of piling up the geo-bags for erosion protection was going on when SANDRP visited the area in the second week of April 2014. The bags which were used previously for the same purpose were seen to be mostly lying in water in shattered condition. Locals told us that majority of the bags are now under water. In the eroded bank line, these geo-bags were lying without any order and in a way suggesting how the river has dealt or to say played with these jumbo bags. In this bank line, there was a stretch of nearly five meters where the river has eroded more than the other parts. At this stretch none of the geo-bags were to be seen.

There were also contradictions regarding when the present erosion protection work at Nimati ghat had started. Some of the shopkeepers of the ghat said that the work of putting up geo-bags started in February 2014. But according to the contractor in charge of the work, the work started in November 2013. Construction or repairing of embankment just few months before the advent of monsoons is one of the constant criticisms, leveled against the Water Resources department of the state and in Nimati too we heard the same complaint.

Is Geo-tube really a ‘permanent solution’ to floods? In the present discourse of floods in Assam this has become a very significant question. The local people have been fed with various information about geo-tube and most of which are wrong. The life of embankment constructed using geo-tube is of 100 years, we were told by the locals when we travelled to the upstream areas of Matmora geo-tube. This is absolutely not true. In fact, for Prof Chandan Mahanta of IIT Guwahati the scouring[1] done by the river Brahmaputra will be the major cause of concern for geo-tube embankments in the long run.

The geo-tube embankment has already faced threat of scouring right after its construction in the monsoons of 2011. It was on the morning of 14th July, 2011 when two of the apron tubes at the tail of the embankment, were launched due to increase force of water. The apron tubes were laid at the toe of the geo-tube embankment and with the increased force of water scoured at the bottom by the embankment toe line. WRD engineers flung into action and immediate repairing work was taken up at the site. According to WRD engineers this had happened because the trees which were left outside the embankment had obstructed and increased the force of water and they were immediately cut down. Concrete porcupines were also thrown into the water. Asomiya Pratidin, a regional newspaper reported this on that day but thereafter no report on this could be found. The incident was almost forgotten. When we visited the geo-tube embankment, it was observed that along the toe-line of the embankment a scour line runs for substantial length of the embankment. This clearly shows that scouring by the river has increased in this area. The news report published in Assam Tribune [2]also points out a significant problem associated with geo-bags – “The lobby is mounting pressure for use of geo-bags in the form of bank revetment. Bank revetment is generally not adopted in Brahmaputra because of many reasons. Most important of them is – it produces a permanent deep channel along the existing riverbank.”

On the issue of lobbying behind geo-tube, an interesting perspective was provided by activist-researcher Keshoba Krishna Chatradhara who coordinates ‘Peoples’ Movement for Subansiri and Brahmaputra Valley (PMSBV)’. He opines that the construction of geo-tube embankment in Matmora was an experiment, done to see whether such embankments can withstand the flood and erosion of Brahmaputra. The reason for choosing Matmora first and not other severe erosion affected places like Dibrugarh or Rohmoria, was because even if the embankment fails it won’t be as significant loss for the state compared to those places. Dibrugarh is one of the most important towns of upper Assam with a glorious history whereas Rohmoria became important for the state when Oil India Limited found oil deposits in Khagorijan[3]. Infact several local people and activists also opined that the Sissi-Tekeliphuta embankment which is on the north bank of the river was cut several times, to save the areas in the upstream south bank, mainly the Dibrugarh town. They said that in the past, before the geo-tube embankment came, whenever there was any news of water rising in Dibrugarh, there would soon be a breach in Sissi-tekeliphuta embankment. In fact considering these breaches in the larger Sissi-tekeliphuta embankment, Mr. Chatradhara opined that even if the geo-tube embankment survives the flood, erosion and breaches in future, it might become a small island in midst of a submerged land as there will surely be breaches in the rest of the Sissi-Tekeliphuta embankment.

ADB loan for Geo-textile Embankments in Assam After the construction of the geo-tube embankment at Matmora, the state government is leaving no stone unturned to make it sound like a glorious success. But it is surprising to know that, even before the Matmora embankment was commissioned in December 2010, the state government have filed proposal for two more embankment project where geo-textile would be used for construction and got it cleared. The two subprojects of Assam Integrated Flood River Bank Erosion Risk Management Project (AIFRERM) in Dibrugarh and Palashbari were cleared in the 106th meeting of TAC held on 16th September 2010. It is important to note that for the total AIFRERM project ADB is giving a loan of $56.9 million. The cost of Dibrugarh and Palashbari subprojects are Rs 61.33 crore and Rs 129.49 crore respectively. But these investments have been cleared without even doing a post-construction impact assessment of Matmora geo-textile embankment. The Palashbari subproject also included erosion protection for Gumi area through the use of geo-bags but the Assam Tribune report quoted above already mentioned about how geo-bags scheme has failed in that area.

It is important to note here that, the first geo-tube embankment has been constructed only three years back and it would be premature to give any verdict of success, on the contrary there are many signs of failure. But the state government of Assam and the Assam Water Resources department are claiming it as success without really any credible basis and than have used that self certification to go on building more embankments using geo-textile and in several occasions these plans have failed. They first should have done a detailed impact assessment of the embankment at Matmora before going on building more embankments of the same nature.

It seems the Assam government, ADB and CWC are pushing these projects to deflect attention from the failure of embankments in flood management. Such attempts won’t succeed, but it is possibly a ploy to prolong the use of embankments as a flood management technique.

Parag Jyoti Saikia (meandering1800@gmail.com)

Annexure 1

Flood and Erosion Projects approved for Assam – 2009 to 2013

| TAC meeting no & date | Project | Appr. year | River/ Basin | L of Emba. (m) | Original (revised) Cost-CrRs | Benefitting area (Ha) | Decision |

| 95th -20.01.2009 | Protection of Sialmari Area from the erosion of Brahmputra | 2002 | Brahmaputra | NA | 14.29 (25.73) | NA | Accepted |

| Protection of Bhojaikhati, Doligaon and Ulubari area from the erosion | 2002 | Brahmaputra | NA | 14.52 (27.92) | NA | Accepted | |

| Raising & strengthening Brahmputra Dyke from from Sissikalghar to Tekeliphuta including closing of breach by retirement and anti erosion measures | New | Brahmaputra | NA | 142.42 | NA | Accepted | |

| 96th -16.02.2009 | Flood protection of Majuli Island from Flood and Erosion Ph-II & III | New | Brahmaputra | NA | 115.03 | NA | Accepted |

| Restoration of Dibang & Lohit rivers to their original courses at Dholla Hattiguli | New | Brahmaputra | NA | 23.32 (53.11) | NA | Accepted partly & suggested that proposal of coffer dam, pilot channel, etc. to be put up for expert opinion | |

| 101st -30.11.2009 | Raising and strengthening to Puthimari embankment | New | Brahmaputra | NA | 30.23 | 15000 | Accepted |

| Anti Erosion measures to protect Brahmputra Dyke on left bank | New | Brahmaputra | NA | 27.97 | 5000 | Accepted | |

| Protection of Gakhirkhitee & adjoining areas from erosion | New | Brahmaputra | NA | 19.06 | 20,000 | Accepted | |

| 102 -28.1.’10 | Emergent measures for protection of Rohmoria in Dibrugarh District | New | Brahmaputra | NA | 59.91 | 18,000 | Accepted |

| 106th -16.09.2010 | Raising and strengthening of tributary dyke along both banks of Kopili River | New | Kopilli/ Brahmputra | NA | 110.72 | NA | Accepted |

| Assam Integrated Flood River Bank Erosion Risk Management Project | New | Brahmaputra | NA | 61.33 | NA | Accepted | |

| Assam Integrated Flood River Bank Erosion Risk Management Project | New | Brahmaputra | NA | 129.49 | NA | Accepted | |

| 110th – 20.07.2011 | Protection of Majuli from Flood and Erosion Ph II & III | 2011 | Brahmaputra | 115.03 | Accepted | ||

| Restoration fo rivers Dibang & Lohit to their original courses at Dholla Hatighuli | 2011 | Brahmaputra | 54.43 | Accepted | |||

| 111th – 17.08.2011 | Protection of Biswanath Panpur including areas of upstream Silamari and Far downstream Bhumuraguri to Borgaon against erosion | New | Brahmaputra | 167.09 | Accepted | ||

| 117 – 21.3.’13 | Protecion of Sissi-Tekeliphuta dyke from erosion – Lotasur to Tekeliphuta | New | Brahmaputra | 153000 m | 155.87 | 153000 m | Accepted |

| 118th – 30.07.2013 | Flood management of Dikrong along with river training works on both banks embankment | New | Dikrong/Brahmaputra | 105.96 | Accepted | ||

| Flood management of Ranganadi along with river training works on both bank embankments | New | Ranganadi/Brahmaputra | 361.42 | Accepted |

[1] Scour can be termed as a specific form of the more general term erosion. In case of geo-tube embankments Scour is the removal of sediment from the bottom of the geo-tubes. Scour, caused by swiftly moving water, can scoop out scour holes, compromising the integrity of a structure.

[2] ADB, river engineers differ on geo-bags – http://www.assamtribune.com/scripts/detailsnew.asp?id=jun2410/at08

[3] See ‘Rohmoria’s Challenge: Natural Disasters, Popular Protests and State Apathy’ published in Economic and Political Weekly, Vol XLVI NO 2, Janurary 8, 2011.

Media Hype Vs Reality: India-China Water Information Sharing MoU of Oct 2013

It was pretty surprising to see the front page headline in The Times of India on Oct 24, 2013[i], claiming that an India China “MoU on Dams Among Nine Deals Signed”. The Hindu headline[ii] (p 12) claimed, “China will be more transparent on trans-border river projects”. Indian Express story[iii] (on page 1-2) claimed, “The recognition of lower riparian rights is a unique gesture, because China has refused to put this down on paper with any other neighbouring country”. It should be added that the news stories on this subject in the Economic Times and the Hindustan Times took the MoU in more matter of fact way.

Source: SANDRP

Additional information for second half of May However, the actual language of the Memorandum of Understanding on “strengthening cooperation on trans-border rivers” available on website of Press Information Bureau[v] and Ministry of External affairs[vi] gives a very different picture. There is no mention of dams, river projects or lower riparian or rights there. One additional feature of the agreement is that the current hydrological data (Water Level, Discharge and Rainfall) in respect of three stations, namely, Nugesha, Yangcun and Nuxia located on river Yaluzangbu/Brahmaputra from 1st June to 15th October every year[vii] will now be extended to May 15th to Oct 15th with effect from 2014. While this is certainly a step forward since the monsoon in North East India sets in May and also in view of the accelerated melting of glaciers in changing climate, it should not lead to the kind of hype some of the newspapers created around the river information MoU. Moreover, it should be remembered that India pays for the information that it gets from China and what Indian government does with that information is not even known since it is not even available in public domain. How this information is thus used is a big state secret!

![Three stations on Yarlung Zangbo - Nugesha, Yangcun and Nuxia (the green spots in the map represent these station)[iv]](https://sandrp.in/wp-content/uploads/2013/10/three-stations-on-on-yarlung-zangbo.jpg?w=663)

(the green spots in the map represent these station)[iv]

Over-Optimistic reading of the MoU? The specific feature of the new MoU about which media seemed excited read as follows: “The two sides agreed to further strengthen cooperation on trans-border rivers, cooperate through the existing Expert Level Mechanism (for detailed chronology of ELM formation, meetings and earlier MoUs on Sutlej and Brahmaputra, see annexure below) on provision of flood-season hydrological data and emergency management, and exchange views on other issues of mutual interest.” The key words of this fifth the last clause of the MoU were seen as “exchange views on other issues of mutual interest”, providing India an opportunity to raise concerns about the Chinese hydropower projects and dams on shared rivers. However, the clause only talks about exchange of views and there is no compulsion for China to share its views, leave aside share information about the Chinese projects in advance or otherwise. On the face of it, the hype from this clause misplaced.

This was read with first clause: “The two sides recognized that trans-border rivers and related natural resources and the environment are assets of immense value to the socio-economic development of all riparian countries.” Here “riparian countries” clearly includes lower riparian. But to suggest that this clause on its own or read with clause 5 mentioned above provides hope that China will include the concerns of the lower riparian in Chinese projects on shared rivers seems slightly stretched. The clause only recognises the asset value of rivers and related natural resources and environment for all basin countries and it is doubtful if it can be used to interpret that Chinese will or should take care of the concerns of lower riparian.

Thus the rather optimistic interpretation does not seem to emanate from the actual wording of the MoU, but the rather over optimistic interpretation by the Indian interlocutors, possibly including the Indian ambassador to China, who has been quoted on this aspect.

Real Achievement: GOI recognises value of Rivers! What is most interesting though is that Indian government has actually signed a Memorandum that recognises that “rivers and related natural resources and the environment are assets of immense value to the socio-economic development”. This is absolutely amazing and joyful development for rivers. Since there is nothing in the laws, policies, programs, projects and practices of Indian government that says that rivers are of any value. Now that Indian government has actually signed an MoU agreeing to such a value, there is sudden hope for rivers, it seems. Only lurking doubt, though is the word “trans-border” before rivers! We hope the Government of India applies this clause to all rivers, not just trans-border rivers, though we know from past that this hope is one a rather thin ice!!

SANDRP

Annexure:

1. Formation and Meetings of Expert Level Mechanism (ELM) on Trans-border Rivers

| 20-23 Nov, 2006 | During the visit of the President of People’s Republic of China to India in November 20-23, 2006, it was agreed to set up an Expert-Level Mechanism to discuss interaction and cooperation on provision of flood season hydrological data, emergency management and other issues of trans-border rivers between the two countries. Accordingly, the two sides set up the Joint Expert Level Mechanism(ELM) on Trans-border Rivers. The Expert Group from Indian side is led by Joint Secretary level officers. Seven meetings of ELM have been held so far. |

| 19-21 Sept, 2007 | In the 1st meeting of ELM the issues related to bilateral cooperation for exchange of hydrological information were discussed. |

| 10-12 April, 2008 | In the 2nd meeting of ELM work regulations of the ELM were agreed upon and signed. It was agreed that the ELM shall meet once every year, alternatively in India and China. |

| 21–25 April, 2009 | The 3rd meeting was focused on helping in understanding of each other’s position for smooth transmission of flood season hydrological data. |

| 26-29 April, 2010 | In the 4th meeting the implementation plan on provision of hydrological information on Yaluzangbu/Brahmaputra River in flood season was signed. |

| 19-22 April, 2011 | In the 5th meeting the Implementation Plan in respect to the MoU on Sutlej was signed. |

| 17-20 July, 2012 | The 6th meeting of ELM was held at New Delhi where both the countries reached at several important understandings and a significant one of those understandings is – “The two sides recognized that trans-border rivers and related natural resources and the environment are assets of immense value to the socio-economic development of all riparian countries.” |

| 14-18 May, 2013 | In the 7th meeting held at Beijing, China where in the draft MoU and Implementation Plan on Brahmaputra river was finalized. |

2. MoUs on Hydrological Data Sharing on River Brahmaputra / Yaluzangbu

| 2002 | Government of India and China signed a MoU for provision of hydrological information on Yaluzangbu/Brahmaputra River in flood season by China to India. In accordance with the provisions contained in the MoU, the Chinese side provided hydrological information (Water Level, Discharge and Rainfall) in respect of three stations, namely, Nugesha, Yangcun and Nuxia located on river Yaluzangbu/Brahmaputra (see the map above) from 1st June to 15th October every year, which was utilized in the formulation of flood forecasts by the Central Water Commission. This MoU expired in 2007. |

| 2008 | On 5th June, India signed a new MoU with China on provision of hydrological information of the Brahmaputra /Yaluzangbu river in flood season by China to India with a validity of five years. This was done during the visit of the External Affairs Minister of India to Beijing from June 4-7. Under this China had provided the hydrological data of the three stations for the monsoon season from 2010 onward. |

| 2013 | During the visit of Chinese Premier Li Kegiang to India the MoU of 2008 has been extended till 5th June 2018. |

3. MoUs on Hydrological Data Sharing on River Satluj / Langquin Zangbu

| 2005 | A MoU was signed during the visit of the Chinese Premier to India in April for supply of hydrological information in respect of River Satluj (Langquin Zangbu) in flood season. Chinese side provided hydrological information in respect of their Tsada station on river Satluj (Langquin Zangbu in Chinese, see the map above). |

| Aug 2010 | In order to supply flood season hydrological information on River Sutlej a new MoU was agreed in August 2010 |

| Dec 2010 | On 16 Dec 2010, during the visit of Prime Minister of China to India a new MoU was signed to provide hydrological information of Sutlej/Langquin Zangbo River in flood season by China to India with a validity of five years. |

| April 2011 | During the 5th ELM meeting held in April, 2011 an MoU on Sutlej containing the Implementation Plan with technical details of provision of hydrological information, data transmission method and cost settlement etc. was signed in Beijing. The hydrological information during the flood season has been received in terms of the signed implementation plan. |

Annexure compiled by Parag Jyoti Saikia

Post Script: Further reading: http://www.thethirdpole.net/2015/11/06/tibet-dams-hold-back-silt-not-water

END NOTES:

[i] http://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/india/India-China-seal-border-pact-talk-Pak-based-terror/articleshow/24619614.cms

[ii] http://www.thehindu.com/todays-paper/tp-national/china-will-be-more-transparent-on-transborder-river-projects/article5266620.ece

Subansiri Basin Study – Another Chapter of Environment Subversion in Northeast

The Study The study has been done by IRG Systems South Asia Private Limited (http://www.irgssa.com/, a subsidiary of US based IRG Systems) and http://www.eqmsindia.com/[i]. It is supposed to be a Cumulative Impact Assessment of 19 HEPs planned in the basin, out of which PFRs of 7 are available, DPR of two, and one of which, the 2000 MW Subansiri Lower HEP is under construction.

The Study The study has been done by IRG Systems South Asia Private Limited (http://www.irgssa.com/, a subsidiary of US based IRG Systems) and http://www.eqmsindia.com/[i]. It is supposed to be a Cumulative Impact Assessment of 19 HEPs planned in the basin, out of which PFRs of 7 are available, DPR of two, and one of which, the 2000 MW Subansiri Lower HEP is under construction.

Subversion of Environment Governance in the Subansiri basin While looking at this basin study, the subversion of environment governance in Subansiri basin this very millennia should be kept in mind. A glimpse of it is provided in Annexure 1. In fact, one of the key conditions of environmental clearance to the 2000 MW Lower Subansiri HEP was that no more projects will be taken up in the basin upstream of the Lower Subansiri HEP, which essentially would mean no more projects in the basin, since LSHEP is close to the confluence of the Subansiri River with Brahmaputra River. That condition was also part of the Supreme Court order in 2004. The need for a carrying capacity study was also stressed in the National Board of Wild Life discussions. We still do not have one. In a sense, the Subansiri basin is seeing the consequences of that subversion.

Source: https://sandrp.in/basin_maps/Subansiri_River_Basin.pdf

Information in public domain not known to consultants The report does not even state that Middle Subansiri dam have also been recommended TOR in 41st EAC meeting in Sept 2010. This project will require 3180 ha of land, including 1333 Ha forest land, and 2867 ha area under submergence. Even about Upper Subansiri, the consultants do not know the area of forest land required (2170 ha). So the consultants have not used even the information available in public domain in EAC meetings.

Study based on flawed and incomplete Lohit Basin Study The Study claims that it is based on Lohit Basin Study done by WAPCOS. Lohit Basin Study is an extremely flawed attempt and does not assess cumulative impacts of the cascade projects. Civil society has written about this to the EAC and the EAC itself has considered the study twice (53rd and 65th EAC Meetings), and has not accepted the study, but has raised several doubts. Any study based on a flawed model like Lohit Basin Study should not be acceptable.

Source: http://cooperfreeman.blogspot.in/2012/12/the-wild-east-epic.html

No mention of Social impacts Major limitation of the study has been absolutely no discussion on the severe social impacts due to cumulative forest felling, flux of population, submergence, livelihoods like riparian farming and fishing, etc. Though this has been pointed out by the TAC in its meeting and field visit, the report does not reflect this.

Some key Impacts Some of the impacts highlighted by the study based on incomplete information about HEPs are:

Þ The length of the river Subansiri is 375 km up to its outfall in the Brahamaputra River. Approximately 212.51 km total length of Subansiri will be affected due to only 8 of the proposed 19 HEPs in Subansiri River basin.

Þ Total area brought under submergence for dam and other project requirements is approx. 10, 032 ha of eight proposed HEPs. The extent of loss of forest in rest of the 9 projects is not available.

Þ 62 species belonging to Mammals (out of 105 reported species), 50 Aves (out of 175 reported species) and 2 amphibians (out of 6 reported species) in Subansiri Basin are listed in Schedules of Wildlife Protection Act, 1972 (as amended till date).

Þ 99 species belonging to Mammals (out of 105 reported species), 57 species belonging to Aves (out of 175 reported species), 1 Reptilian (out of 19 reported species), 2 Amphibians (out of 6 reported species), 28 fishes (out of 32 reported species), 25 species belonging to Odonata of Insecta fauna group (out of 28 reported species) are reported to be assessed as per IUCN’s threatened categories.

Even this incomplete and partial list of impacts should give an idea of the massive impacts that are in store for the basin.

Cumulative impacts NOT ASSESSED Specifically, some of the cumulative impacts that the report has not assessed at all or not adequately include:

1. Cumulative impact of blasting of so many tunnels on various aspects as also blasting for other project components.

2. Cumulative impact of mining of various materials required for the projects (sand, boulders, coarse and fine granules, etc.)

3. Cumulative impact of muck dumping into rivers (the normal practice of project developers) and also of also muck dumping done properly, if at all.

Source: Lovely Arunachal

4. Changes in sedimentation at various points within project, at various points within a day, season, year, over the years and cumulatively across the basin and impacts thereof.

5. Cumulative impact on aquatic and terrestrial flora and fauna across the basin due to all the proposed projects.

6. Cumulative impact of the projects on disaster potential in the river basin, due to construction and also operation at various stages, say on landslides, flash floods, etc.

7. Cumulative dam safety issue due to cascade of projects.

8. Cumulative change in flood characteristics of the river due to so many projects.

9. Cumulative impacts due to peaking power generation due to so many projects.

10. Cumulative sociological impact of so many projects on local communities and society.

11. Cumulative impact on hydrological flows, at various points within project, at various points within a day, season, year, over the years and cumulatively across the basin and impacts thereof. This will include impacts on various hydrological elements including springs, tributaries, groundwater aquifers, etc. This will include accessing documents to see what the situation BEFORE project and would be after. The report has failed to do ALL THIS.

12. Impact of silt laden water into the river channel downstream from the dam, and how this gets accumulated across the non-monsoon months and what happens to it. This again needs to be assessed singly and cumulatively for all projects.

13. Impact of release of silt free water into the river downstream from the power house and impact thereof on the geo morphology, erosion, stability of structures etc, singly and cumulatively.

14. Impact on Green House Gas emissions, project wise and cumulatively. No attempt is made for this.

15. Impact of differential water flow downstream from power house in non-monsoon months, with sudden release of heavy flows during peaking/ power generation hours and no releases during other times.

16. Cumulative impact of all the project components (dam, tunnels, blasting, power house, muck dumping, mining, road building, township building, deforestation, transmission lines, etc.,) for a project and then adding for various projects. Same should also be done for the periods during construction, operation and decommissioning phases of the projects.

17. Cumulative impact of deforestation due to various projects.

18. Cumulative impact of non compliance of the environment norms, laws, Environment clearance and forest clearance conditions and environment management plans. Such an assessment should also have analysed the quality of EIA report done for the Subansiri Lower hydropower project.

Wrong, misleading statements in Report There are a very large number of wrong and misleading statements in the report. Below we have given some, along with comment on each of them, this list is only for illustrative purposes.

| Sr No |

Statement in CIA |

Comment |

| 1 | “During the monsoon period there will be significant discharge in Brahmaputra River. The peaking discharge of these hydroelectric projects which are quite less in comparison to Brahmaputra discharge will hardly have any impact on Brahmaputra.” | This is a misleading statement. It also needs to be assessed what will be the impact on specific stretches of Subansiri river. Secondly, the projects are not likely to operate in peaking mode in monsoon. |

| 2 | “However, some impact in form of flow regulation can be expected during the non-monsoon peaking from these projects.” | This is not correct statement as the impact of non-monsoon peaking is likely to be of many different kinds, besides “flow regulation” as the document describes. |

| 3 | “Further, during the non-monsoon period the peaking discharge release of the projects in upper reaches of Subansiri basin will be utilized by the project at lower reaches of the basin and net peaking discharge from the lower most project of the basin in general will be the governing one for any impact study.” | This is again wrong. What about the impact of such peaking on rivers between the projects? |

| 4 | “The construction of the proposed cascade development of HEPs in Subansiri basin will reduce water flow, especially during dry months, in the intervening stretch between the Head Race Tunnel (HRT) site and the discharge point of Tail Race Tunnel (TRT).” | This statement seems to indicate that the consultants have poor knowledge or understanding of the functioning of the hydropower projects. HRT is not one location, it is a length. So it does not make sense to say “between HRT and the discharge point of TRT”. |

| 5 | “For mature fish, upstream migration would not be feasible. This is going to be the major adverse impact of the project. Therefore, provision of fish ladder can be made in the proposed dams.” | This is simplistic statement without considering the height of the various dams (124 m high Nalo HEP dam, 237 m high Upper Subansiri HEP dam, 222 m high Middle Subansiri HEP dam), feasibility of fish ladders what can be optimum design, for which fish species, etc. |

| 6 | “…water release in lean season for fishes may be kept between 10-15% for migration and sustaining ecological functions except Hiya and Nyepin HEP. Therefore, it is suggested that the minimum 20% water flow in lean season may be maintained at Hiya and Nyepin HEP for fish migration.” | This conclusion seems unfounded, the water release suggested is even lower than the minimum norms that EAC of MoEF follows. |

Viability not assessed The report concludes: “The next steps include overall assessment of the impacts on account of hydropower development in the basin, which will be described in draft final report.”

One of the key objective of the Cumulative Impact assessment is to assess how many of the planned projects are viable considering the impacts, hydrology, geology, forests, biodiversity, carrying capacity and society. The consultants have not even applied their mind to key objective in this study. They seem to assume that all the proposed projects can and should come up and are all viable. It seems the consultant has not understood the basic objectives of CIA. The least the consultant could have said is that further projects should not be taken up for consideration till all the information is available and full and proper Cumulative impact assessment is done.

The consultants have also not looked at the need for free flowing stretches of rivers between the projects.

Section on Environmental Flows (Chapter 4 and 9): The section on Environmental flows is one of the weakest and most problematic sections of the report, despite the fact that the Executive summary talks about it as being one of the most crucial aspects.

The study does not use any globally accepted methodology for calculating eflows, but uses HEC RAS model, without any justification. The study has not been able to do even a literature review of methodologies of eflows used in India and concludes that “No information/criteria are available for India regarding requirement of minimum flow from various angles such as ecology, environment, human needs such as washing and bathing, fisheries etc.”

This is unacceptable as EAC itself has been recommending Building Block Methodology for calculating eflows which has been used (very faultily, but nonetheless) by basin studies even like Lohit, on which this study is supposedly based. EAC has also been following certain norms about E flow stipulations. CWC itself has said that minimum 20% flow is required in all seasons in all rivers. BK Chaturvedi committee has recently stipulated 50% e-flows in lean season and 30% in monsoon on daily changing basis.

The assumption of the study in its chapter on Environmental Flows that ‘most critical reach is till the time first tributary meets the river” is completely wrong. The study should concentrate at releasing optimum eflows from the barrage, without considering tributary contribution as an excuse.

First step of any robust eflows exercise is to set objectives. But the study does not even refer to this and generates huge tables for water depths, flow velocity, etc., for releases ranging from 10% lean season flow to 100% lean season flow.

After this extensive analysis without any objective setting, the study, without any justification (the justification for snow trout used is extremely flawed. Trouts migrate twice in a year and when they migrate in post monsoon months, the depth and velocity needed is much higher than the recommended 10% lean season flow) recommends “In view of the above-said modeling results, water release in lean season for fishes maybe kept between 10-15% for migration and sustaining ecological functions except Hiya and Nyepin HEP. Therefore, it is suggested that the minimum 20-25% water flow in lean season may be maintained at all HEP for fish migration and ecological balance.”

The study does not recommend any monsoon flows. Neither does it study impact of hydro peaking on downstream ecosystems.

Shockingly, the study does not even stick with this 20-25% lean season flow recommendation (20-25% of what? Average lean season flow? Three consecutive leanest months? The study does not explain this). In fact in Chapter 9 on Environmental Flows, the final recommendation is: “Therefore, it is suggested that the minimum 20-25% water flow in lean season may be maintained at Hiya and Nyepin HEP or all other locations for fish migration.” (emphasis added)

So it is unclear if the study recommends 20-25% lean season flows or 10-15% lean season flows. This is a very flawed approach to a critical topic like eflows.

The study keeps mentioning ‘minimum flows’ nomenclature, which shows the flawed understanding of the consultants about e-flows.

The entire eflows section has to be reworked, objectives have to be set, methodology like Building Block Methodology has to be used with wide participation, including from Assam. Such exercises have been performed in the past and members of the current EAC like Dr. K.D. Joshi from CIFRI have been a part of this. In this case, EAC cannot accept flawed eflows studies like this. (DR. K D. Joshi has been a part of a study done by WWF to arrive at eflows through BBM methodology for Ganga in Allahabad during Kumbh: Environmental Flows for Kumbh 2013 at Triveni Sangam, Allahabad and has been a co author of this report)

Source: http://www.flickr.com/photos/8355947@N05/7501485268/

Mockery of rich Subansiri Fisheries Subansiri has some of the richest riverine fisheries in India. The river has over 171 fish species, including some species new to science, and forms an important component of livelihood and nutritional security in the downstream stretches in Assam.

But the study makes a mockery of this saying that the livelihoods dependence on fisheries is negligible. The entire Chapter on Fisheries needs to be reworked to include impacts on fisheries in the downstream upto Majuli Islands in Assam at least.

No mention of National Aquatic Animal! Subansiri is one of the only tributaries of Brahmaputra with a resident population of the endangered Gangetic Dolphin, which is also the National aquatic animal of India (Baruah et al, 2012, Grave Danger for the Ganges Dolphin (Platanista ganegtica) in the Subansiri River due to large Hydroelectric Project. http://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10669-011-9375-0#).

Shockingly, the Basin Study does not even mention Gangetic Dolphin once in the entire study, let alone making recommendations to protect this specie!

Gangetic Dolphin is important not only from the ecological perspective, but also socio cultural perspective. Many fisher folk in Assam co-fish with the Gangetic River Dolphin. These intricate socio ecological links do not find any mention in the Basin study, which is unacceptable.

Source: SANDRP

Lessons from Lower Subansiri Project not learnt A massive agitation is ongoing in Assam against the under construction 2000 MW Subansiri Lower HEP. The people had to resort to this agitation since the Lower Subansiri HEP was going ahead without studying or resolving basic downstream, flood and safety issues. The work on the project has been stopped since December 2011, for 22 months now. In the meantime several committee have been set up, several changes in the project has been accepted. However, looking at this shoddy CIA, it seems no lessons have been learnt from this ongoing episode. This study does not even acknowledge the reality of this agitation and the issues that the agitation has thrown up. There is no reflection of the issues here in this study that is agitating the people who are stood up against the Lower Subansiri HEP. The same people will also face adverse impacts of the large number of additional projects planned in the Subansiri basin. If the issues raised by these agitating people are not resolved in credible way, the events now unfolding in Assam will continue to plague the other planned projects too.

Conclusion From the above it is clear that this is far from satisfactory report. The report has not done proper cumulative assessment on most aspects. It has not even used information available in public domain on a number of projects. It does not seem to the aware of the history of the environmental mis-governance in the SubansiriBasin as narrated in brief in Annexure 1. For most projects basic information is lacking. Considering the track record of Central Water Commission functioning as lobby FOR big dams, such a study should have never been given to CWC. One of the reasons the study was assigned by the EAC to the Central Water Commission was that the CWC is supposed to have expertise in hydrological issues, and also can take care of the interstate issues. However, the study has NOT been done by CWC, but by consultants hired by CWC, so CWC seems to have no role in this except hiring consultant. So the basic purpose of giving the study to CWC by EAC has not been served. Secondly the choice of consultants done by the CWC seems to be improper. Hence we have a shoddy piece of work. This study cannot be useful as CIA and it may be better for EAC to ask MoEF for a more appropriate body to do such a study. In any case, the current study is not of acceptable quality.

South Asia Network on Dams, Rivers & People (https://sandrp.in/, https://sandrp.wordpress.com/)

—

ANNEXURE 1

Set Conditions to be waived Later – The MoEF way of Environmental Governance

In 2002, the 2,000 MW Lower Subansiri hydroelectric project on the Assam-Arunachal Pradesh border came for approval to the Standing Committee of the Indian Board for Wildlife (now called the National Board for Wildlife) as a part of the Tale Valley Sanctuary in AP was getting submerged in the project. The total area to be impacted was 3,739.9 ha which also included notified reserved forests in Arunachal Pradesh and Assam. The Standing Committee observed that important wildlife habitats and species well beyond the Tale Valley Sanctuary, both in the upstream and downstream areas, would be affected (e.g. a crucial elephant corridor, Gangetic river dolphins) and that the Environmental Impact Assessment studies were of a very poor quality. However, despite serious objections raised by non-official members including Bittu Sahgal, Editor, Sanctuary, Valmik Thapar, M.K. Ranjitsinh and the BNHS, the Ministry of Environment & Forests (MoEF) bulldozed the clearance through in a May 2003 meeting of the IBWL Standing Committee. Thus a project, which did not deserve to receive clearance, was pushed through with certain stringent conditions imposed (Neeraj Vagholikar, Sanctuary Asia, April 2009).

Source: The Hindu

The EC given to the project was challenged in Supreme Court (SC) by Dr L.M Nath, a former member of the Indian Board for Wildlife. Nath pleaded, these pristine rich and dense forests classified as tropical moist evergreen forest, are among the finest in the country. Further the surveys conducted by the Botanical Survey of India and the Zoological Survey of India were found to be extremely poor quality. The Application mentions that the Additional DG of Forests (Wildlife) was of the view that the survey reports of the BSI and ZSI reports were not acceptable to him because these organisations had merely spent five days in the field and produced a report of no significance.

The SC gave its final verdict on 19-4-2004, in which the Court upheld the EC given by MoEF to NHPC but with direction to fulfill some important conditions. Out these conditions there were two conditions which were very significant – “The Reserve Forest area that forms part of the catchment of the Lower Subansri including the reservoir should be declared as a National Park/ Sanctuary. NHPC will provide funds for the survey and demarcation of the same.”, and “There would be no construction of dam upstream of the Subansri River in future.” These conditions were also mentioned in the original EC given to the project in 2003.

In May 2005, two years after the EC was given the Arunachal Pradesh govt and NHPC approached the SC to waive or modify the above two conditions. The state government calimed that following these conditions would imply loss of opportunity to develop 16 mega dams in the upstream of Lower Subansiri (this including 1,600 MW Middle Subansiri and 2,000 MW Upper Subansiri to be developed by NHPC). The SC sent it back to National Board for Wildlife to review the conditions.

The petition was done strategically. “The strategy of the dam proponents is simple. They raised no objection to the terms until the construction of the Lower Subansiri project had proceeded beyond a point when it could have been cancelled. Armed with this fait accompli, they asked for a review of the clauses on the very basis on which the original clearance – laid down by members who were subsequently dropped from the wildlife board – was granted.”[ii]