MESSAGE ON WORLD ENVIRONMENT DAY 2014:

SAVE HIMALAYAS FROM THIS HYDRO ONSLAUGHT!

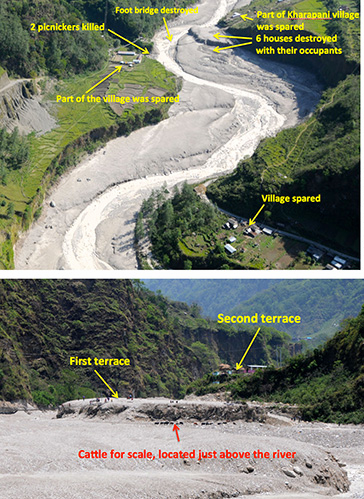

It is close to a year after the worst ever Himalayan flood disaster that Uttarakhand or possibly the entire Indian Himalayas experienced in June 2013[1]. While there is no doubt that the trigger for this disaster was the untimely and unseasonal rain, the way in which this rain translated into a massive disaster had a lot to do with how we have been treating the Himalayas in recent years and today. It’s a pity that we still do not have a comprehensive report of this biggest tragedy to tell us what happened during this period, who played what role and what lessons we can learn from this experience.

One of the relatively positive steps in the aftermath of the disaster came from the Supreme Court of India, when on Aug 13, 2013, a bench of the apex court directed Union Ministry of Environment and Forests (MoEF)[2] to set up a committee to investigate into the role of under-construction and completed hydropower projects. One would have expected our regulatory system to automatically initiate such investigations, which alas is not the case. Knowing this, some us wrote to MoEF on July 20, 2013[3], to exactly do such an investigation, but again MoEF played deaf and blind to such letters.

The SC mandated committee was set up through an MoEF order dated Oct 16 2013[4] and MoEF submitted the report on April 16, 2014.

The committee report, signed by 11 members[5], makes it clear that construction and operation of hydropower projects played a significant role in the disaster. The committee has made detailed recommendations, which includes recommendation to drop at least 23 hydropower projects, to change parameters of some others. The committee also recommended how the post disaster rehabilitation should happen, today we have no policy or regulation about it. While the Supreme Court of India is looking into the recommendations of the committee, the MoEF, instead of setting up a credible body to ensure timely and proper implementation of recommendations of the committee has asked the Court to appoint another committee on the flimsy ground that CWC-CEA have submitted a separate report advocating more hydropower projects! The functioning of the MoEF continues to strengthen the impression that it is working like a lobby for projects rather than an independent environmental regulator. We hope the apex court see through this.

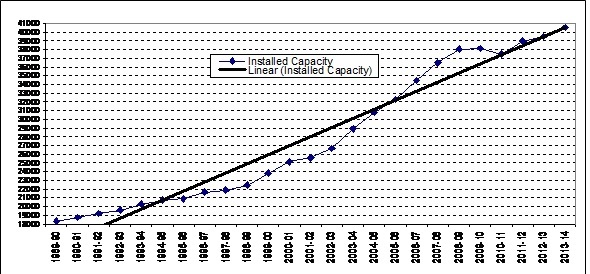

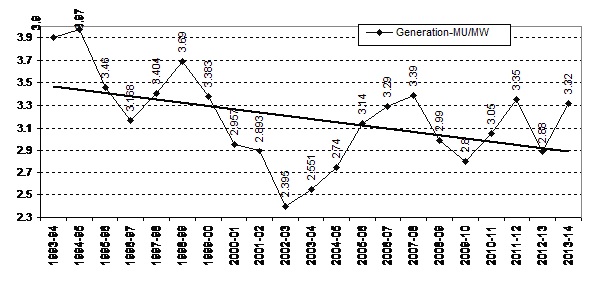

Let us turn our attention to hydropower projects in Himalayas[6]. Indian Himalayas (Himachal Pradesh, Uttarakhand[7], Jammu & Kashmir, Sikkim, Arunachal Pradesh and rest of North East) already has operating large hydropower capacity of 17561 MW. This capacity has leaped by 68% in last decade, the growth rate of National Hydro capacity was much lower at 40%. If you look at Central Electricity Authority’s (CEA is Government of India’s premier technical organisation in power sector) list of under construction hydropower projects in India, you will find that 90% of projects and 95% of under construction capacity is from the Himalayan region. Already 14210 MW hydropower capacity is under construction. In fact CEA has now planned to add unbelievable 65000 MW capacity in 10 years (2017 to 2027) between 13th and 14th Five Year Plans.

Meanwhile, the Expert Appraisal Committee of Union Ministry of Environment and Forests on River Valley Projects has been clearing projects at a break-neck speed with almost zero rejection rate. Between April 2007 and Dec 2013[8], this committee recommended final environment clearance to 18030.5 MW capacity, most of which has not entered the implementation stage. Moreover, this committee has recommended 1st stage Environment clearance (what is technically called Terms of Reference Clearance) for a capacity of unimaginable 57702 MW in the same period. This is indicative of the onslaught of hydropower projects which we are likely to see in the coming years. Here again an overwhelming majority of these cleared projects are in Himalayan region.

Source: SANDRP

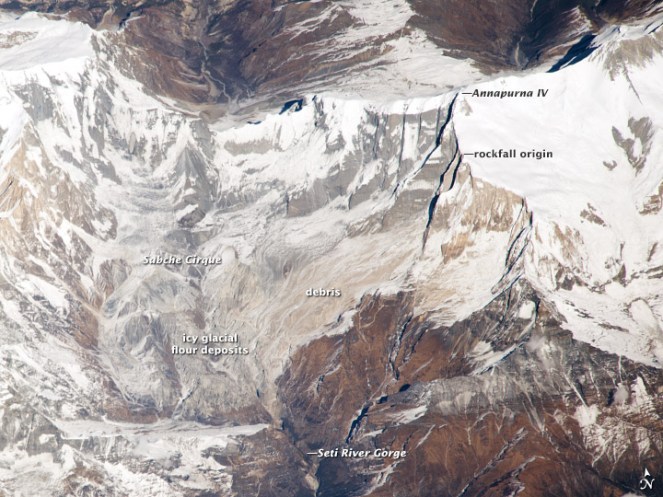

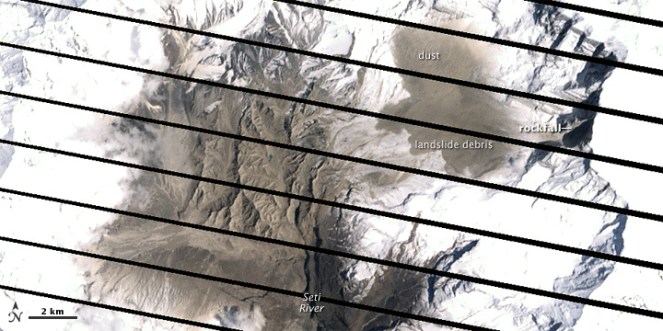

What does all this mean for the Himalayas, the people, the rivers, the forests, the biodiversity rich area? We have not even fully studied the biodiversity of the area. The Himalayas is also very landslide prone, flood prone, geologically fragile and seismically active area. It is also the water tower of much of India (& Asia). We could be putting that water security also at risk, increasing the flood risks for the plains. The Uttarakhand disaster and changing climate have added new unknowns to this equation.

We all know how poor are our project-specific and river basin-wise cumulative social and environmental impact assessments. We know how compromised and flawed our appraisals and regulations are. We know how non-existent is our compliance system. The increasing judicial interventions are indicators of these failures. But court orders cannot replace institutions or make our governance more democratic or accountable. The polity needs to fundamentally change, and we are still far away from that change.

The government that is likely to take over post 2014 parliamentary elections has an opportunity to start afresh, but available indicators do not provide such hope. While UPA’s failure is visible in what happened before, during and after the Uttarakhand disaster, the main political opposition that is predicted to take over has not shown any different approach. In fact NDA’s prime ministerial candidate has said that North East India is the heaven for hydropower development. He seems to have no idea about the brewing anger over such projects in Assam and other North Eastern states. That anger is manifest most clearly in the fact that India’s largest capacity under-construction hydropower project, namely the 2000 MW Lower Subansiri HEP has remained stalled for the last 29 months after spending over Rs 5000 crores. The NDA’s PM candidate also has Inter Linking of Rivers (ILR) on agenda. Perhaps we have forgotten as to why the NDA lost the 2004 Parliamentary elections. The arrogant and mindless pursuit of projects like ILR and launching of 50 000 MW hydropower campaign by the then NDA government had played a role in sowing the seeds of people’s anger with that government.

In this context we also need to understand what benefits these hydropower projects are actually providing, as against what the promises and propaganda are telling us. In fact our analysis shows that the benefits are far below the claims and impacts and costs are far higher than the projections. The disaster shows that hydropower projects are also at huge risk in these regions. Due to the June 2013 flood disaster large no of hydropower projects were damaged and generation from the large hydro projects alone dropped by 3730 million units. In monetary terms this would mean just the generation loss at Rs 1119 crores assuming conservative tariff of Rs 3 per unit. The loss in subsequent year and from small hydro would be additional.

It is nobody’s case that no hydropower projects be built in Himalayas or that no roads, townships, tourism and other infrastructure be built in the Himalayan states. But we need to study the impact of these massive interventions (along with all other available options in a participatory way) in what is already a hugely vulnerable area, made worse by what we have done so far in these regions and what climate change is threatening to unleash. In such a situation, such onslaught of hydropower projects on Himalayas is likely to be an invitation to even greater disasters across the Himalayas. Himalayas cannot sustain this onslaught.

It is in this context, that the ongoing Supreme Court case on Uttarakhand provides a glimmer of hope. It is not just hydropower projects or other infrastructure projects in Uttarakhand, or for that matter in other Himalayan states that will need to take guidance from the outcome of this case, but it could provide guidance for all kinds of interventions all across Indian Himalayas. Our Himalayan neighbors can also learn from this process. Let us end on that hopeful note here!

Himanshu Thakkar (ht.sandrp@gmail.com)

END NOTES:

[1] For SANDRP blogs on Uttarakhand disaster of June 2013, see: https://sandrp.wordpress.com/?s=Uttarakhand

[2] For details of Supreme Court order, see: https://sandrp.wordpress.com/2013/08/14/uttarakhand-flood-disaster-supreme-courts-directions-on-uttarakhand-hydropower-projects/

[3] https://sandrp.wordpress.com/2013/07/20/uttarakhand-disaster-moef-should-suspect-clearances-to-hydropower-projects-and-institute-enquiry-in-the-role-of-heps/

[4] For Details of MoEF order, see: https://sandrp.wordpress.com/2013/10/20/expert-committee-following-sc-order-of-13-aug-13-on-uttarakhand-needs-full-mandate-and-trimming-down/

[5] https://sandrp.wordpress.com/2014/04/29/report-of-expert-committee-on-uttarakhand-flood-disaster-role-of-heps-welcome-recommendations/

[6] https://sandrp.wordpress.com/2014/05/06/massive-hydropower-capacity-being-developed-by-india-himalayas-cannot-take-this-onslought/

[7] https://sandrp.wordpress.com/2013/07/10/uttarakhand-existing-under-construction-and-proposed-hydropower-projects-how-do-they-add-to-the-disaster-potential-in-uttarakhand/

[8] For details of projects cleared during April 2007 to Dec 2012, see: https://sandrp.in/env_governance/TOR_and_EC_Clearance_status_all_India_Overview_Feb2013.pdf and https://sandrp.in/env_governance/EAC_meetings_Decisions_All_India_Apr_2007_to_Dec_2012.pdf

[9] An edited version of this published in June 2014 issue of CIVIL SOCIETY: http://www.civilsocietyonline.com/pages/Details.aspx?551