As we stood on a ridge near the Lakke Wali Mata shrine, a tributary of the Ravi roared below in a deep gorge. Across it rose a shaded, Devdar (Himalayan Cedar)-covered mountain slope, etched by a steep brown trail. As we stood there observing the headwaters of Ravi, we noticed that the trail was moving.

And so it was. A steady line of white sheep was treading along the slope. Heading the flock was a fluffy dog with alert ears and behind the flock trailed two shepherds in gray wool coats and colorful Himachali hats. They were the Gaddis: semi-nomadic, semi-pastoral transhumant (the seasonal movement of livestock (and herders) between fixed summer and winter pastures) tribe of the Ravi Basin who have walked along these mountain paths and passes for centuries.

Himalayas are home to many transhumant communities like Anwals, Bakarwals, Bhotiyas, Kanets, Van Gujjars and Gaddis who move with their animals in the mountains and plains. But Gaddis, who herd sheep and goats, are the living heritage of Ravi Basin. For several centuries, they have been undertaking a journey from the plains of Punjab or Himachal in the spring, across the Dhauladhar and Pir Panjal ranges and onto the drier, bracing pastures of Lahaul. In the winter, they travel back to the plains, retracing an age-old journey of their ancestors. Most of their journey is through the heart of the Ravi Basin and when they cross the passes in the summers, they enter the Chenab Basin.

Bharmour, the ancient capital of Chamba in the headwaters of Ravi is known as Gadderan1, or the traditional home of the Gaddis. But then, ‘home’ is a fluid concept for a community that spends 3 months in Lahaul, 3 months in the plains, some months in Bharmour and most of the time on the road. They travel from 100 meters to more than 4000 meters in altitude2 with their animals and can cover up to 1000 kms on foot a year.

Gaddis are the memory keepers of the mountains and a veritable reference book of stories, songs, observation and insights into the forests, rivers, climate, snow, glaciers, pastures, medicinal plants, grasses and even wildlife. They are the followers of Lord Shiva and consider Shiva to be the original shepherd of the Himalayas. Through festivals like ‘Shiv Nuala’, they sing about the oral history of the Gaddi community as well as the landscape.

The Gaddis personify and integrate Lord Shiva into their lifestyle and believe that he equipped the Gaddi not only with a herd of sheep and grass shoes (pulan) for traversing rugged landscapes to the mountain pastures but also with a woolen cloak (chola), a belt (dora), and other items to combat the cold. The Gaddis’ migratory patterns to summer and winter abodes (kailasha and pyalpuri) mirror Shiva’s own movements and are embedded in their belief system.3 Sacred Geography is so enmeshed in Gaddi life that the old Gaddi hat was symbolised the peak of Manimahesh Kailash, from where Budhil River originates.4

‘Gaddi’ today encompasses various castes categories including Brahmins, Rajputs, Khatris, Ranas, Thakurs, and Rathis. Scholars have noted that it is their settlement in the plains of Kangra (Himachal Pradesh) that led to this adoption of social categories to assimilate into the society where Gaddis settled.5

Meenu Ram, the leader of the group, 51, told us that they wanted to cross the mountains through the pass at Kuwarsi Naag shrine (approx. 2800 meters altitude), but could not do so due to early snow at the pass. They will now have to look for a new path. They are moving to Ranital in Kangra, about 270 kms from Holi. Meenu Ram has been traveling with the sheep for 30 years now and said that he or his elders never saw rains or floods like the 2025 monsoon. They were in the high mountains at that time and had to stay put in their tents for months. “We saw ice blocks flowing through the rivers in January and December.”

He told us that Gaddis take permission of local deity to cross the pass at the Kuwarsi Naag shrine. The shrine has a sacred Devdar tree and a water source which is protected strictly. “This is Naag Devta Pradesh (Land of the snake deity). Here the weather can change in a minute and entire flocks can be lost. We trust gods more than people here.”

While the British, who were interested in the Himalayan forests only as a never-ending source of timber, considered Gaddis as harming the forests, the reality of Gaddi coexistence with the landscape is complex. Apart from supreme landscape-knowledge (a study recorded 92 plant species used by gaddis in various ways6), Gaddis nurture and protect several community-conserved areas like sacred groves, sacred trees, sacred lakes and spring origins, they worship mountain springs and zealously protect them from harm, and are extremely careful with the mountain passes which are gateways to summer pastures and no less revered than the abode of their deities.

Passes like Kugti, Chobia, Jalsu, Kali Cho, Kuwarsi are marked by shrines and very strict community rules about the number of flocks that can cross each pass on a given day.

Studies show that not only do Gaddis have strong views about the climate, but their reminiscences are validated when checked against climate data7. They can be invaluable sources of climate-related information for the mountains. At the same time, climate change, increasing trend of temperature and erratic but overall deceasing trend in rainfall, coupled with changing land use patterns have affected Gaddi migration, as we witnessed first-hand. So much so that some studies say Gaddi pastoralism is “on the verge of extinction.”8

A combination of factors: development policies, education and healthcare, access to pastures, infrastructure like dams, changing climate and disasters, theft of animals, increasing exotic species in pastures, etc., the flock size and number of sheep and goats held by Gaddi shepherds are declining rapidly over time. Even afforestation policies and compensatory afforestation by the slew of hydropower dams in the Ravi Basin9 are affecting Gaddi’s access to routes and pastures. None of these activities consult Gaddis as a bona fide stakeholder.

Studies indicate that permits given to Gaddis recorded by the Forest Department are also declining rapidly, indicating a shifting trend.

And yet, even today, thousands of Gaddis move through the landscape, scaling the heights of Himalayas and back every year, collecting invaluable ecological and climate data with them, embellishing it in songs and stories. If only we listen to their stories and work with them.

Gaddi youth, listening to music on their cellphones as they walk past a hydropower dam that has altered the flow of the Ravi, carry two worlds with them. One is woven from the remembered paths, seasonal passes, deities who guard snow and rivers, songs sung on the move, and a life calibrated to weather, grass, water and time. The other is shaped by dams, roads, shrinking pastures, erratic snow and floods, theft, and a future that demands stillness from people who have always lived in motion.

Gaddis are not only shepherds. They are storytellers and memory keepers of mountains, forests and rivers—living archives of climate, glaciers, pastures and passes. If they disappear from these landscapes, it will not only be a livelihood that vanishes, but a way of knowing rivers like the Ravi, and the landscape, that will be lost with them.

Photographs: Abhay Kanvinde, Independent Photojournalist; Story: Parineeta Dandekar, SANDRP

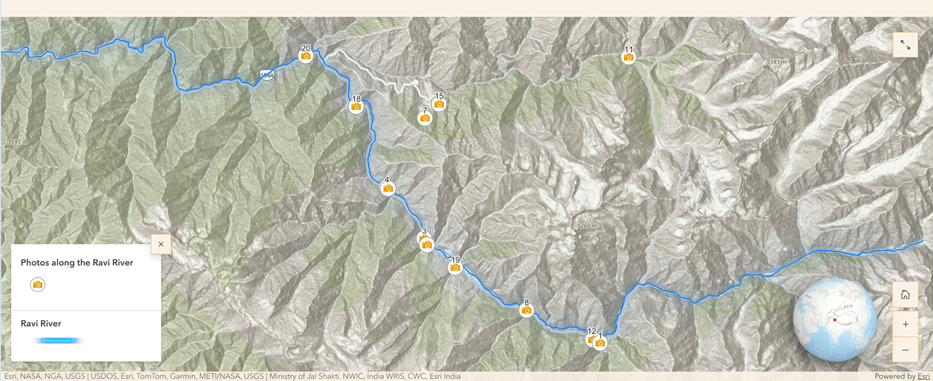

This Phototstory is a part of Ohio State University’s River Ethnographies Project. Storymap version: https://storymaps.arcgis.com/stories/a9c2adb1ad9c4c6f9cf210139419f5a8, Story map created by: Michelle Hooper, Dept. Of Geography OSU

References:

1 Mukherjee et al, 1994, Eco degradation and Future of Pastoralism: Gaddi of Himachal Pradesh

2 Sharma M., 2015, Ritual, Performance, and Transmission: The Gaddi Shepherds of Himachal Himalayas

3 Nehria et al, 2024, Gaddi: Himachal Pradesh’s evolving pastoral tribe

4 Theuns -de Boer, G, 2008, A Vision of Splendor

5 Sharma, M, 2015, Ritual, Performance, and Transmission: The Gaddi Shepherds of Himachal Himalayas

6 Sharma et al, 2022, Moving away from transhumance: The case of Gaddis

7 Sharma et al, 2020, Documentation and validation of climate change perception of an ethnic community of the western Himalaya

8 Mishra et al, 2023, Trapped within nature: climatic variability and its impact on traditional livelihood of Gaddi transhumance of Indian Himalayas

9 Ramprasad et al, 2020, Plantations and pastoralists: afforestation activities make pastoralists in the Indian Himalaya vulnerable, Sheth et al, 2020, Pastoralism in Transition: Anecdotes from Himachal Pradesh – A Commentary