The state of Himachal Pradesh has a hydropower potential of almost 23,000 MW, which is about one-sixth of the country’s total potential[1]. In a bid to harness it, the state authorities seem to have gone all out without really even assessing the costs and impacts it will have on the local ecology and people. It has already developed about 8432.47 MW till now and is racing towards increasing that and in its way, displacing people, destroying forests and biodiversity, drying the rivers, disrupting lives and cultures in upstream and downstream, and flooding cultivable and forest land. The target of the State government for 2013-14 is to commissioning 2000 MW[2] capacity projects. The state and central governments are pushing for more and more projects, playing havoc with the lives of the locals and thus facing continuous agitations. This update tries to provide some glimpses in hydropower sector in Himachal Pradesh over the last one year.

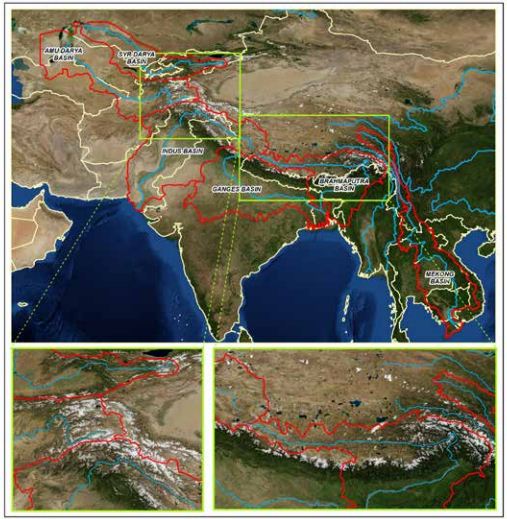

The Ravi, Sutlej, Chenab, Beas & Yamuna, which form the major river basins of Himachal have been heavily dammed. These projects submerge and bypass the rivers, change the course, the flow and the silt carried by the rivers. The 27 proposed projects in the Chenab basin endanger the fragile ecosystem of the Lahaul-Spiti Valley. In the Sutlej, the nine major hydel projects of 7623 MW which are already running along the 320 km stretch include: 633 MW Khab (proposed), 960 MW Jangi Thopan & Thopan Pawari (re-bidding), 402 MW Shongtong Karcham (under execution), 1,000 MW Karcham Wangtoo (commissioned), 1,500 MW Nathpa Jhakari (commissioned), 412 MW Rampur (under execution), 588 MW Luhri (allotted)[3]. There are about 21 more proposed projects. The same is the case with the Ravi where about 30 projects are proposed to be built or are already functional.

From 1981-2012, more than 10,000 ha of forest land on which people had user rights, have been diverted for hydropower, mining, roads and other projects[4]. This does not include the thousands of hectares of forest land diverted towards projects like the Bhakra Dam before 1980.

On the one hand, the Ministry of Environment and Forests (MoEF) treats the locals like hindrances, saying that they cause damage to the environment by using the forests inefficiently, on the other hand, it approves big projects which cause hundred times more damage to the environment. There is no recognition of the ecological fragility of the landscape, and clearance from the MoEF seems like just a formality. Clearly, the MoEF and the state government are not interested in doing something for the people of the area, but in pushing project constructions to achieve targets at whatever cost it may require. This is also evident in the way the MoEF, without proper consultation, approved the state’s request for making the procurement of no-objection certificates (NOCs) from the Gram Sabhas a non requirement. MoEF itself had passed a circular in 2009, making it mandatory for project proponents to obtain NOCs of the affected Gram Sabhas and compliance to the Forest Rights Act 2006 before the diversion of forest land to non forest purposes. However, in 2012, the MoEF issued a letter which stated that there are no compliance issues with regard to FRA in Himachal Pradesh since the rights of the forest dwellers have already been settled under the Forest Settlement Process in the 1970s[5]. This is clearly wrong and not supported by facts or ground realities.

Taking away the rights of people on land without giving them adequate compensation has been a governmental trend. It is not enough to just grant monetary compensation to them. The land which could be put to various uses by the local is no longer his. The Gaddis, a shepherding community, rely a great deal on their rights over land as they need it for grazing. With the Forest Dept. making some areas inaccessible for them, their land has anyways decreased. In addition to this, projects like the Bajoli-Holi and the proposed dam at Bada Bhangal, which is sanctuary area now, and traditionally a grazing area for the Gaddis, will further take away from the available land.

Run-of-the –river projects:

But it is not only the loss of forest and private land which is the problem here. Another major issue is that of water. With the state giving increased priority to run-of –the –river projects, more and more water from the river is being diverted for longer stretches.

In the controversial Luhri project on the river Sutlej, the diversion of water into a 38 km long tunnel would mean the absence of free flowing river in stretch of almost 50 kms. The agreed amount of water to be left flowing in the river is 25% for the lean season and 30% in monsoon[6]. The project was initially supposed to be of 775 MW installed capacity and was to have two tunnels. This was challenged because higher environmental discharge was to be maintained in the downstream river. The capacity has been reduced to 600 MW and there will be only one tunnel[7].

But even this diversion would mean that villages falling within 50 km downstream of the project will not have access to its water like they used to. It will also lead to the warming up of the valley as the cool waters will be diverted into the tunnel. The environmental impact assessments (EIAs) have failed to address the effects of this. The EIA has also done no assessment of the impact of the tunnels on the land and people over ground. Locals have been agitating under the banner of Sutlej Bachao Jan Sangharsh Samiti, but the project is still on[8].

Another major drawback of the tunneling process is the danger it poses to the residing population and their groundwater sources. The Karcham Wangtoo project (1000 MW) in Kinnaur, which is the country’s largest hydropower project in the private sector (owned by the Jaiprakash Associates) was closed briefly in the December of 2012, due to leakage from the surge shaft and the water-conducting system, raising concerns about the safety of such projects and the absence of a monitoring body[9]. Because of the massive dam, the leakage was between 5-9 cumecs (cubic meters per second) or 5000-9000 liters per second, which is large enough to trigger massive landslides in the area. The company involved in the project will always try to get away saying that such things are unforeseen and it will take time for the project to stabilize. But in the meanwhile, who should be held accountable for the losses to life, livelihoods, habitats and environment due to this?

The same project involves a 17 km long tunnel passing under 6 villages The tunnell has affected water aquifers causing natural springs to dry up. This claim by the villagers was verified by the state’s Irrigation and Public Health department in a response to an RTI application. The official data showed that 110 water sources have been affected by this project. This information has come out only due to the proactive-ness of local people, but these issues are not even part of the impact assessments.

The concerns expressed by locals in the case of the 180 MW Holi-Bajoli project are quire serious. This project on the Ravi River has been given clearances under suspicious circumstances. It is being opposed by the local communities on issues of environment, violation of rights, and impacts on local livelihoods. People have also taken offense at the apathy shown to them by the state government. The tunnel for the project was supposed to be constructed on the right bank of the river, which is relatively devoid of habitation, but the powerhouse and headrace tunnel sites were later shifted to the left bank, on which rest most of the villages of the area. This decision was seen as flawed according to a report by the state-run Himachal Pradesh State Electricity Board Ltd (HPSEBL), which pointed out that it could have negative effects on the environment and the locals. The reason being cited for this is that construction on the right bank would take longer to be completed. GMR’s contention was that the right bank was weak and unsuitable, whereas the opposite has been confirmed by a Geological Survey of India report according to Rahul Saxena of the NGO Himdhara Environment Research Collective[10].

The protests which have been going on for four years now have been due to legitimate concerns raised by the locals of deforestation, loss of land and infrastructure and the loss of peace which would accompany the project. Earlier this year, women of four panchayats set up camp at the proposed site of the power house at Kee Nallah near Holi village to stage their protests. 31 of these women were arrested for protesting against the illegal felling of trees and the road construction of the project. They were taken to Chamba town which is almost 70 kms away from Holi and were detained for more than 24 hours despite appeals for their immediate release. Though they were released on bail the next day, they say that a lot of false charges have been filed against them. The district administration has taken no steps to resolve these issues[11]. In a letter to the Chief Secretary, the people have demanded that all charges be dropped against these women and justice be done about their demands. Despite continuous protests by the people the MoEF has given clearance to this project which requires the diversion of 78 ha of rich forest land and the felling of 4995 treesx.

The locals also say that change in the MoEF policy of NOCs enabled the Deputy Commissioner to issue a false certificate under FRA saying that no rights have to be settled on the land diverted for the project as it has already been done under the settlement process of 1970s.

Management glitches:

In the Chamera II and III projects on Ravi River, there has been much debate about the distance between the two being only 1.5 km without any water source in the middle. The operation of the Chamera II power station is completely dependent on the release by upstream Chamera III project. If the generation schedules of both are very different, there will be danger to the downstream areas. Last year it was observed that the schedules given by the Regional load Dispatch center were not coordinated, resulting in a dis-balance in the generation in both dams. In another instance, leakage was noted in the head race tunnel of Chamera III HEP.[12]

In a letter to the Chief Minister last year, environmental activists sought to know why there has been no committee set up by the State government for the control and monitoring of safety and water flows as is required by the Hydropower Policy 2006 of Himachal.

In another case of delay and mismanagement among many others, the Kol Dam on Sutlej River, the foundation for which was laid by former prime minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee in the year 2000, was due to be completed in 2008 but is not yet functional. The Majathal Wildlife Sanctuary area falls in the submergence area for the project and clearance was required from the National Board for Wildlife as the project would endanger 50,000 trees and the habitat of the ‘cheer pheasant’[13]. The project was finally granted approval by the Supreme Court in December 2013, given permission to drown the proposed parts of the sanctuary. The whole episode smacks of a scam when the project authorities say they forgot to get the clearance for submergence of the sanctuary and the forest & wildlife departments are ready to look away.

But due to continuous delays trigged by shoddy work and project management, the NTPC Dam project has still not been made functional. The delay is expected to be for at least another year, which would mean an additional loss of Rs. 150 crore. For about a year now the NTPC has been claiming that the filling of the reservoir would start, but they had to abandon that twice due to heavy leakages. There are also problems with the gates fitted inside the diversion tunnel and also additional repairs are needed in the tunnel.[14]

No State responsibility for environment:

The Comptroller and Auditor General of India (CAG) has found that the hydro power projects are not adhering to the compensatory afforestation that was promised. Out of the projects it studied, it found that 58% of them have carried out no afforestation activities at all. According to the results of an audit, it was seen that only 12 companies had deposited compensation money out of which no work was done at all in seven of the projects. Even out of the 12, full afforestation was achieved on paper only in 2 of them[15].

Another major problem is that tunnelling and road construction generate huge amounts of muck and debris. These are not disposed off in the right manner. For example, in the Koldam, the net volume of muck generated is 2.27 crore cubic metres. If this was to be dumped in the Sutlej, it would lead to a raise in the level of the Sutlej by 2.20 metres along a length of 100 kms[16]. The project authorities, including the World Bank funded projects like Rampur and Nathpa Jakhri, find it easier to dump the muck into the river rather than transport and dump it properly. The MoEF, state government and all concerned are happy to not take any action against any of the projects for such blatant violations that everyone knows about and even when evidence of such violations are presented to them.

Small Hydel Projects (SHPs):

The view of the government regarding the non requirement of clearances for small projects is clearly unfounded, unscientific and unacceptable. If the authorities think that these projects cause no or little harm to the environment and the people, they are wrong. The fact is that a lot of the hydro power potential of Himachal Pradesh is envisioned to be realized through these small projects which are being indiscriminately built on even small tributaries of the major rivers, sometimes even the ones listed as negative (from fisheries perspective) for HEPs.

In a recent case, the 4.8 MW Aleo II project located on the Aleo nallah, a tributary of the Beas River, in Kullu district, made news due to the collapse of its reservoir wall in a trial run[17]. The Aleo II project was supposed to become functional in January 2014, but as the management started to fill the 12,000 cubic meter capacity reservoir, its wall collapsed when it was only 75% full. The water from the reservoir went straight into the Beas River, causing sudden rise in its levels till about 50 kms downstream. The management had not informed the panchayat or the public of Prini village which is situated next to the dam site before attempting to fill the reservoir, causing unforeseen danger to them and others downstream.

These small projects[18] also seem to be working without proper lease of land. In a report earlier this year, it was found that out of the 55 projects examined below the 5 MW capacity in Himachal Pradesh, about 47 of them are operating without proper lease of the forest land that they are using. It was found after an RTI was filed regarding this that about 35.973 ha of land in the Chamba district was being used without lease by 13 HEPs. The case was similar in Kangra with about 43.5035 ha being used without lease. This just goes to show that the State regulations regarding hydro projects are not strict and definitely faulty. The land is being ruthlessly exploited by private and public sector companies which have a bullying attitude towards the local population[19].

Excessive electricity? Reports suggest that the state requires about 1200 MW of power, but it is producing so much more that it has no buyers. It is not surprising to see that projects like the 1000 MW Karcham Wangtoo in Kinnaur are facing lack of buyers for electricity. The JPHL has not been able to sign long term Power Purchase Agreements (PPAs) with any power distribution company (discoms). As a result, it is selling electricity through short term agreements or at lower prices. This is the situation with a lot of other plants in the state, both private and public. Even the state is facing difficulties selling its surplus power and as a result has to sell it at lower prices. According to a 2012 report of the CAG, the revenue earned from selling surplus power in Himachal has dropped significantly over the past years. The reason given for this is mostly the increased cost of production which has made power more expensive and the discoms, which are already in debt are thus unable to buy it.[20] Even after facing such losses, why is it that the Himachal government is pushing for more and more projects, destroying the rivers, forests, biodiversity, livelihoods and environment?

To add to the worries of the local people and environmentalists, in a recent announcement, the Chief Minister has announced that there is no NOC required from the fisheries dept, IPH, PWD and the revenue dept for small projects[21] Also, to make things easier for the project developers, it was announced that the small projects below 2 MW installed cpacity, were now liable to give the government only 3% of free power for a period of 12 years, as opposed to the earlier 7%xvi.

In an interesting development of the first ever Cumulative Environmental Impact Assessment (CEIA) in the state, a study of 38 hydro electric power projects in the Sutlej basin, the recommendation has been to designate the “fish-rich khuds, mid-Sutlej, eco-sensitive Spiti, Upper Kinnaur area and 10 other protection areas as a no-go zone for hydro projects”[22]. The CEIA is incomplete, inadequate and makes a lot of unwarranted assumptions and uscientific assertions. Even if this recommendation implemented, several projects in the Sutlej basin are still under way and the government seems to be doing nothing to stop them. There is also an Environmental Master Plan (EMP) prepared by the Department of Environment and Scientific Technology, and approved by the government which claims to have identified the vulnerable areas of the State[23]. This EMP is being adopted by the State for its developmental planning for the next 30 years. But the impact of this is yet to be seen, assuming that it does not turn out to be one of those plans which are never implemented.

Padmakshi Badoni, SANDRP, padmakshi.b@gmail.com

END NOTES:

[1] http://www.downtoearth.org.in/content/drowned-power

[2] http://indiaeducationdiary.in/Shownews.asp?newsid=24595

[3] http://www.hindustantimes.com/India-news/HimachalPradesh/Review-hydropower-projects-on-Sutlej-Kinnaur-residents/Article1-1101869.aspx

[4] http://tehelka.com/himachal-pradesh-government-flunks-forest-rights-subject/

[5] http://www.himdhara.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/05/Press-Note-20th-Jan-2013.pdf

[6] http://articles.timesofindia.indiatimes.com/2013-02-24/chandigarh/37269688_1_luhri-project-mw-luhri-river-project

[7] www.energylineindia.com February 24, 2013.

[8] http://www.tribuneindia.com/2013/20130222/himachal.htm

[9] http://www.tribuneindia.com/2013/20130128/himachal.htm#7

[10] http://www.newstrackindia.com/newsdetails/2013/08/18/229–Hydro-project-site-shift-disastrous-Himachal-government-.html

[11] http://www.himdhara.org/2014/04/17/press-release-all-womens-independent-fact-finding-team-visits-holi-expresses-solidarity-with-local-struggle/

[12] www.energylineindia.com may 16, 2013.

[13] www.enrgylineindia.com January 24, 2013

[14] http://www.tribuneindia.com/2014/20140417/himachal.htm#11

[15] http://zeenews.india.com/world-environment-day-2013/world-environment-day-hydro-projects-causing-degeneration-of-hill-ecology_853017.html

[16] http://hillpost.in/2013/07/the-uttarkhand-apocalypse-is-himachal-next/93449/

[17] http://www.himdhara.org/2014/03/24/run-into-the-river/

[18] For details of impacts of small HEPs in Himachal Pradesh, see: https://sandrp.wordpress.com/2014/06/08/the-socio-ecological-effects-of-small-hydropower-development-in-himachal-pradesh/ and https://sandrp.wordpress.com/2014/06/11/the-socio-ecological-impacts-of-small-hydropower-projects-in-himachal-pradesh-part-2/

[19] http://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/india/Majority-of-small-hydel-projects-in-Himachal-Pradesh-operate-sans-land-lease/articleshow/28696581.cms

[20] . http://www.downtoearth.org.in/content/drowned-power

[21] http://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/india/Budget-sops-to-make-investments-in-hydro-power-attractive/articleshow/30079948.cms

[22] http://www.tribuneindia.com/2014/20140704/himachal.htm#15