There is a rush of riverfront development schemes in India. We have heard of Sabarmati Riverfront development being drummed many times, followed by the proposed rejuvenation of Ganga, supposedly on the lines of Sabarmati.

What does Riverfront Development entail? Is it River Restoration? Are the millions of rupees spent on Riverfront Development schemes justified? Will it help in saving our damaged rivers?

A cursory glance at the existing river restoration/ improvement/beautification schemes indicates that the discourse revolves mainly around recreational and commercial activities. It is more about real estate than river. Activities that are promoted on the riverfronts typically include promenades, boat trips, shopping, petty shops, restaurants, theme parks, walk ways and even parking lots in the encroached river bed.

Pioneering project in Riverfront Development was claimed to be the Sabarmati Riverfront Development project of Ahmedabad city which was supposed to be designed based on riverfronts of Thames in London and Seine in Paris. The project which began as an urban development project is lately being pushed as a role model for many urban rivers in India. This kind of riverfront development essentially changes the ecological and social scape of the river transforming it into an urban commercial space rather than a natural, social, cultural, ecological landscape. Is it wise to go for this kind of development on riverfronts? What does it do to the river ecosystem, its hydrological cycle? What does it do to the downstream of river? These questions need to be explored before accepting the current model of riverfront development as replicable or laudable.

Reclaim and beautify!

Most of the currently ongoing projects lay a heavy emphasis on beautification of rivers. Riverfronts are treated as extension of urban spaces and are often conceived as ‘vibrant’, ‘throbbing’ or ‘breathing’ spaces by the designers. Concrete Wall Embankments, reclamation of the riverine floodplains and commercialization of the reclaimed land are the innate components of these projects. Quick glimpse at various Riverfront Development Projects confirms this.

Sabarmati Riverfront Development Project

Sabarmati Riverfront Development Project of Ahmedabad city which is presented as a pioneer in urban transformation[1] has been proposed by Environmental Planning Collaborative (EPC), an Ahmedabad-based urban planning consultancy firm, in 1997 and envisaged to develop a stretch of 10.4 km of the banks on both sides of the river by creating concrete embankment walls on both banks with walkways. A Special Purpose Vehicle called the Sabarmati Riverfront Development Corporation Ltd. (SRFDCL) was formed in the same year for implementation of the project. The financial cost of the initiative was estimated to be in the range of around INR 11520 million[2]. Around two thirds of this amount has already been spent.

Construction of the project started in 2005. The project sought to develop the riverfront on either side of the Sabarmati for 10.4 kms by constructing embankments and roads, laying water supply lines and trunk sewers, building pumping stations, and developing gardens and promenades[3]. Mainstay of the project was the sale of riverfront property. Land along the 10.4 km stretch on both the banks was reclaimed by constructing retaining walls of height ranging from 4 to 6m[4]. 21% of the 185 ha of reclaimed land which was developed by concretizing the river bank[5] was sold to private developers for commercial purpose.[6] Activities hosted on this reclaimed land were recreational and commercial activities like restaurants, shops, waterfront settlements, gardens, walkways, amusement parks, golf course, water sports and some for public purpose like roads etc. The sale of reclaimed land created by the project is expected to cover the full cost of the project. Ahmedabad Municipal Corporation (AMC) claims that the after the project “river has added vibrancy to the urban landscape of Ahmadabad with its open spaces, walkways, well-designed gardens along with activities which contribute to economic growth.”[7]

Even though the project has been modeled as “best practice” by several financing institutions[8], it has also drawn severe criticism for poor rehabilitation of the displaced (rehabilitation happened only after High Court orders following a public interest petition) disrupting the nexus of shelter, livelihood and services of urban poor, lack of transparency in the execution and for tampering with the carrying capacity of the river. No Environment Impact Assessment of the project has been conducted nor any credible public consultation process held.

Sabarmati channel has been uniformly narrowed to 275 metres during the riverfront development project, when naturally average width of the channel was 382 metres and the narrowest cross-section was 330 metres[9]. In this attempt of “pinching the river”[10], the original character of the river is changed completely from seasonally flowing river to an impounded tank illegally taking water from Narmada Canal[11]. River banks have been treated as land that is wasted on which value could be created by reclaiming and not as seasonal ecological systems with floodplains as an integral part of its flows (Baviskar 2011). Seasonality of the river is destroyed and fauna and avi fauna on edges have been damaged. No thought has been given for protection, sustenance or enhancement of the riverine ecosystem. The water that is now impounded in this stretch is not even Sabarmati river water, but Narmada River Water, on which the city of Ahmedabad or Sabarmati has no right, it’s the water meant for drought prone areas of Kutch, Saurashtra and North Gujarat.

The River Sabarmati itself was a perennial river till the Dharoi Dam in the upstream stopped all water at least in non Monsoon months, making the river dry. The stretch flowing through Ahmedabad was carrying the mostly untreated sewage of Ahmedabad city and toxic effluents from the City and district industries.

In the name of Sabarmati River front development, no cleaning of the river has happened, the project has only transferred the water from both banks to the river downstream from Vasna barrage, which is situated downstream from the city. The Vasna barrage stops and stores the water released from Narmada Main Canal that crosses the river about 10.4 km upstream from the barrage. Thus this 10.4 km stretch of the river now holds the Narmada water and huge losses from the stretch are losses for the drought prone areas.

The reclaimed land and the narrowing of the channel have been tampering with the carrying capacity of the river. The project was stalled during August 2006 to March 2007 due to heavy floods[12]. Prior to the floods, the river’s maximum carrying capacity was calculated at 4.75 lakh cusecs on basis of the rainfall over last 100 years[13]. The floods however proved the calculation wrong. National Institute of Hydrology (NIH) and Indian Institute of Technology Roorkee (IITR) were asked to re-evaluate the project design, in the light of the river’s carrying capacity, and see whether the execution of the project would damage the river’s ecology[14]. Report by the NIH, Roorkee in 2007 said “the calculations did not take into account any simultaneous rainfall over the entire catchment area”[15]. This means that the carrying capacity was based only on the water flow from the Dharoi Dam (which is upstream of Ahmedabad City) and not from other places in the river’s catchment until Ahmedabad that also contribute to the volume of water in the Sabarmati. This report states that the riverfront development is “not a flood control scheme”, and that the municipal corporation will have to work out other measures to meet the impending challenge of floods.

The project is also heavily criticized for the poor rehabilitation of the evicted slum population. Large scale eviction was being carried out in an utmost non-transparent manner. A public interest litigation (PIL) was filed in the Gujarat High Court by Sabarmati Nagarik Adhikar Manch (SNAM) or Sabarmati Citizens Rights Forum, supported by several other non-governmental organisations (NGOs) to ensure that the rehabilitation plan was shared with them and to bring transparency to the process. According to the high court orders, at least 11,000 affected families were to be rehabilitated and resettled by AMC. Demolition drive went on without ensuring rehabilitation. Over 3,000 people have moved to a marshland in the outskirts of city with negligible compensation, little & infrequent access to drinking water and minimal sanitation facilities[16].

“The ecology of the river is being transformed to satisfy the commercial greed of a select few,” said Darshni Mahadevia of CEPT, expressing concerns about riverfront ‘beautification’[17].

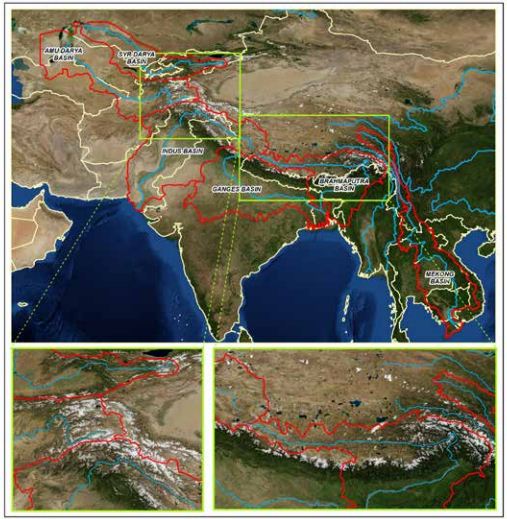

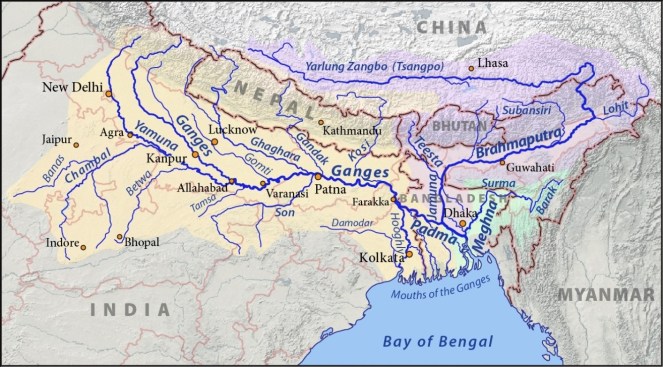

The project that has converted the Sabarmati River into an urban space by reclaiming nearly 200 ha of land and has sustained by borrowing water from Narmada Canal today is claimed to be a role model for many riverfront development projects in the country. Should this model really be replicated? Many of the rivers like Yamuna, Ganga, Mithi, Brahmaputra etc. that are being ‘developed’, have had a flood history which is being ignored in the process. With having no regards to the hazards of floods, several riverfront projects are being pushed across the country by different government agencies.

The fact that even after a Riverfront Development Project, Water Quality of Sabarmati downstream the Vasna Barrage is extremely poor and the cosmetic treatment of flowing water stretch at Ahmedabad is actually water from Narmada, which was promised for the drought hit regions of Kutch and Saurashtra, highlights the contradictory and superficial nature of such Riverfront development schemes.

Yamuna Riverfront Development inspired from Sabarmati Model

Recently the newly elected BJP led Central Government sent a team of bureaucrats to Gujarat to study the feasibility of replicating the successful model of the Sabarmati Riverfront Development Project for cleaning the Yamuna[18]. Despite the concerns about flooding of Yamuna, the team is exploring ways of replicating Sabarmati Model. In 2009, the Sheila Dikshit administration was also planning channelizing the Yamuna and putting up a waterfront like Paris and London with recreational facilities, parking lots and promenades etc[19].

Reclamation of the floodplains to create a concrete riverfront, like in Ahmedabad, could be ecologically unsound and even dangerous for Delhi that is already extremely vulnerable to floods[20]. The sediment load in Yamuna is very high. The non-channelized river rises by over four metres during peak monsoon flooding[21]. Risk of flooding will increase multifold for a channelized river. The Inter-governmental Panel on Climate Change last year put Delhi among three world cities at high risk of floods. Tokyo and Shanghai are the two other cities.

An expert committee appointed by the Ministry of Environment & Forests (MoEF) to examine the Yamuna River Front Development Scheme of the Delhi Development Authority (DDA) recommended that DDA should scrap its ambitious plan for developing recreational facilities, parking lots and promenades. [22] The committee was formed following order from National Green Tribunal which was drawn in response to a petition filed by activists and Yamuna Jiye Abhiyaan convener Manoj Misra.[23] The committee pointed out that recreational spots located in active floodplain areas would kill the river and cause floods in the city. About the Sabarmati Model Being followed, CR Babu, Chair of the committee said: “There is no Sabarmati river. It’s stagnant water with concrete walls on two sides. The floodplains have been concretized to make pathways and real estate projects. It cannot be replicated for our Yamuna”.

The committee report says the Yamuna Riverfront Development scheme will reduce the river’s flood-carrying capacity and increase flooding and pollution and it recommended a ban on developmental activity in the river’s Zone ‘O’ and its active floodplains on the Uttar Pradesh side. It also said that a 52-km stretch of the Yamuna in Delhi and Uttar Pradesh be declared a ‘conservation zone’ as restoring the river’s ecological functions is heavily dependent on the environmental flow through this stretch, particularly in the lean season.

Manoj Misra of Yamuna Jiye Abhiyan, dismisses the Sabarmati solution saying “We cannot call it a Sabarmati model… It’s like a mirage created for a brief stretch. Let’s be clear about it. If the Delhi bureaucrats have gone there to learn from the Gujarat model, it’s up to them to figure out if it can be implemented. I cannot call the Sabarmati project a river rejuvenation project – it’s more of a real estate project… That is not advisable for Delhi.” [24]

Another important aspect which does not feature at all during the talks of Yamuna Riverfront Development is the massive displacement that will take place. Over a dozen unauthorised colonies are located on the riverbed. These colonies which have been in existence for over 40 years will have to be uprooted which again may lead to Sabarmati like situation where urban poor are brushed aside to serve interests of real estate developers and urban middle class.[25]

City of Noida on the other hand has decided to go ahead with the Rs 200 crore Yamuna Riverfront Development Project that Greater Noida Authority (GNA) has been planning[26]. The project involves developing recreational facilities like parks, Yoga centres, picnic spots and sports centres, polo grounds, golf course etc. on Hindon and Yamuna floodplains. Officials from GNA claim that these facilities will be for recreational purpose and will be developed without disrupting the natural flow of Yamuna. Here again the project has nothing to do with sustaining, cleaning, rejuvenation of the river.

Ganga cannot be ‘developed’ as Sabarmati

Prime Minister Narendra Modi made a promise during his election campaign in Varanasi to clean up Ganga.[27] The National Ganga River Basin Authority (NGRBA) was shifted from the environment ministry to the water resources ministry.[28] New name for the Ministry of Water Resources is Ministry of Water Resources, River Development and Ganga Rejuvenation. Uma Bharati was assigned with this specially created ministry for cleaning Ganga by the PM. “If Sabarmati can be cleaned, all other rivers can also be made better.” print media has quoted Uma Bharati.[29] Ms Uma Bharati seems to have no idea that Sabarmati has NOT been cleaned, the Sabarmati project just transferred the polluted water downstream of the 10.4 km stretch. Can Sabarmati Model be replicated at Ganga? Even if it is replicated, will it help the cause or river or river rejuvenation? The answer is clearly a BIG NO. A number of apprehensions have been raised in this regard. “The so-called Sabarmati model won’t work for the Ganga. The Sabarmati has neither been cleaned nor rejuvenated,” Openindia News quotes Himanshu Thakkar, environmentalist and coordinator of SANDRP[30]. He further points out that

Sabarmati Model survives on water from Narmada canal in the stretch of 10.4 km which flows through the Ahmedabad city. This is not possible in case of Ganga.

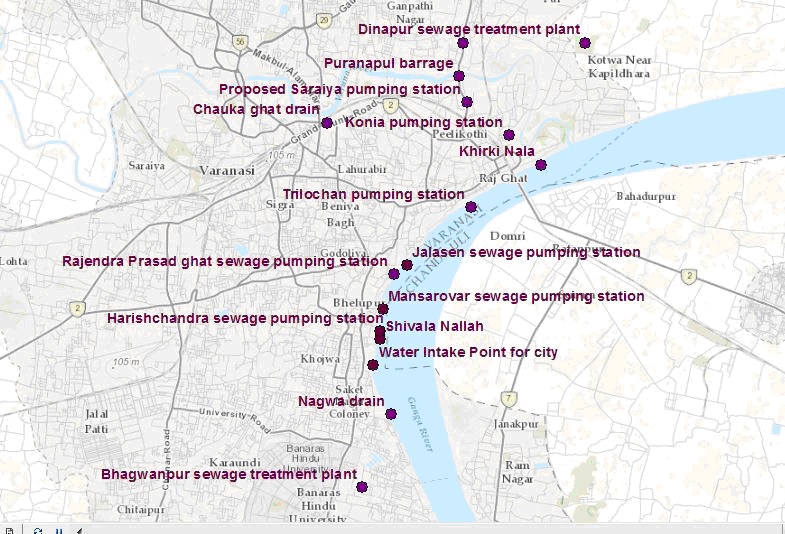

Priority for the river rejuvenation is restoring its water quality, freshwater flow and not riverbank beautification. More than Rs. 5,000 crore (some estimates this figure to be over Rs 20 000 crores) has been spent on cleaning the Ganga in the past 28 years. The Ganga Action Plan was launched in 1986 and was in 1994 extended to the Yamuna, Gomti and other tributaries of the Ganga. The second phase of the Ganga Action Plan was launched in 2000 and NGRBA was created in 2009.[31] The plan however has not achieved what it set out to achieve. Water quality for Ganga River has been declining and is unfit even for irrigation or bathing. Potable use is out of question. The count of harmful organisms, including hazardous faecal bacteria, at many locations is more than 100 times the limit set by the government. The water’s biochemical oxygen content, which is vital for the survival of aquatic wildlife, has dipped drastically.[32] Any “cosmetic treatments”[33] will not work for Ganga, like they have not worked for Sabarmati.

Several Riverfront Development Projects springing up across nation

While there are experts opposing replication of Sabarmati Riverfront Project on Ganga and Yamuna River, there are several other riverfront projects which are inspired by the Sabarmati Project and which are being pushed without any kind of studies or impact assessment. Their possible impacts on the riverine ecology, flood patterns, downstream areas etc. are going unchecked.

Brahmaputra Riverfront Development Project: Another “multi-dimensional environment improvement and urban rejuvenation project” that is set to come up with plans for reclaimed river banks is on Brahmaputra River in Guwahati[34]. While on one hand the city is struggling to cope up with the flood prone nature of the Brahmaputra River, State Government of Assam plans to take up an ambitious project to develop the city riverfront named ‘Brahmaputra Riverfront Development Project’ under the Assam Infrastructure Financing Authority. The riverfront project will be implemented by the Guwahati Metropolitan Development Authority (GMDA) in phases[35]. Foundation of the beautification project was laid by the Chief Minister Tarun Gogoi in February 2013. The project plans to achieve maximum possible reclamation[36].While the plan talks of revitalization of the river ecology and Strengthening of riverbanks through soil bio engineering it has several urban features on its agenda like promenade, Ghats, Plazas and Parks; buildings, conference facilities, Parking lots, ferry terminals, Bus and para transport stops, Urban utilities and drainage, Improved infrastructure for floating restaurants, Public amenities; Dhobi Ghats, etc.[37]

Will such a huge real estate development leave any room for river or its revitalization?

Tendency to flood is an important feature of River Brahmaputra. The river also has one of the highest sediment loads in the world. Every year during the successive floods, most of the areas in the valley of Assam remain submerged for a considerable numbers of days causing wide spread damages. In a phenomenon as recent as June 27, 2014 Guwahati experienced heavy downpour for 15 hours, setting off flash floods[38]. Half of the city was submerged under flood water. The authorities blamed illegal encroachments on watersheds across the state capital for the flash floods, which had choked the natural outlets for the gushing water. National Institute of Hydrology (NIH), Roorkee; upon being requested by the GMDA; is carrying out a study which includes river shifting analysis for studying stability of the river banks, flow variations to determine the perennial water depth, estimate of floods of various return periods for design of river embankments, estimate of water surface profiles employing hydro-dynamic river flow model and design parameters for river embankments[39]. The Bramhaputra Riverfront Development Project however has been inaugurated even before the requisite studies have been completed.

Gomti Riverfront Development Project in Lucknow: The project by the Lucknow Development Authority is based on the Sabarmati Riverfront Model. It plans to “beautify” Gomti River between Gomti Barrage and Bridge on Bye-pass road connecting Lucknow-Hardoi road and Lucknow-Sitapur road, a length of about 15 Km. According to the Technical Bid Document released by the Lucknow Development Authority, the Riverfront Project has no component of water treatment or river restoration, but is a landscape-based development project, which will also look at “reclaiming” the river banks for activities like shops, entertainment area, promenades, etc. The inspiration for the project swings from Thames Rivefront in London, to Sabarmati in Gujarat, depending on the political party in power.[40]

In all this discussion, there is no mention of maintaining adequate flow in Gomti, treating sewage, conserving its floodplains, or any other ecological angles.

River Improvement and Restoration are also about real estate!

For many government agencies, ironically, not just river beautification, but the idea of river improvement and restoration is also about channelizing rivers and providing recreational facilities.

Pune Rivefront Project: Pune Municipal Corporation, the Pune city also known for chronically polluting Mula and Mutha rivers that flow through the heart of the city, has sanctioned a River Improvement Project, under the aegis of JNNURM (Jawaharlal Nehru National Urban Renewal Mission). The Project envisages channelizing the river, introducing barrages to maintain water levels, development of riparian zone as entertainment and shopping groups, even Parking lots, introducing navigation in the river etc. There are several issues with this “improvement” project. Firstly, it is not planned according to the once in a hundred years flood in Pune, it plans to constrict the river further, thus encroaching the riverbed. Creation of stagnant pools through barrages will result in backwater effect on the many nallahs that join the river. These Nallahs routinely flood in rainy season and additional backwater in these nallahs will worsen the situation further. The project does not say a word about treating water quality, but envisages to build drainage lines inside the riverbed and carry the sewage out of Pune city limits. This hardly qualifies as river rejuvenation or restoration. A case has been filed against this project in National Green Tribunal.

Goda Park (Godavari Riverfront Project) in Nashik, Maharashtra: Godavari emerging from the Brahmagiri Hills in Nashik is famed not only for being one of the longest rivers in India, but also because Kumbh Mela is held on its banks every 12 years in Nashik. Nashik and Trimbakeshwar have had no dearth of funding for cleaning Godavari. They have received funds from the National River Conservation Directorate as well as JNNURM. Despite this, Godavari is extremely filthy in Nashik. Ignoring the pressing issues of water quality, Nashik Municipal Corporation and a specific political party have been hankering after beatification of Godavari’s banks. In fact, the project has been handed over to Reliance Foundation by the Nashik Municipal Corporation[41] without any public consultations or discussions. As per reports, the components of this 13.5 kms long project will be laser shows, musical fountains, rope-way, multi-purpose meeting hall, garden, water sports, canteen, etc.[42]

In the meantime, there are several court orders against Nashik Municipal Corporation pending about severe water pollution in the River including Ram Kund where holy dip on Kumbh Mela is supposed to be taken.

Mithi Riverfront Development: Stretch of 18 km of Mithi River flows through city of Mumbai. Course of Mithi has been modified throughout the city to host range of activities.[43] On 26 July 2005, the river flooded some of the most densely populated areas claiming nearly 1000 lives[44].

After these catastrophic floods, the Municipal Corporation of Greater Mumbai (MCGM) and Mumbai Metropolitan Region Development Authority (MMRDA) made a plan to “restore” the river. BMC and MMRDA’s definition of restoration involves desilting, beautification and building of a retaining wall. Stretch of 4.5 km of the total six km stretch of the river that falls within MMRDA’s jurisdiction is covered with mangroves. MMRDA has planned to beautify the stretch of remaining 1.5 km (10 Ha) which lies right amidst mangroves by developing a promenade. MMRDA plans developing this project on a PPP (Public Private Partnership) basis. Interestingly, the Mukesh Ambani-led Reliance Foundation and Standard Chartered bank have been selected for this project.[45]

As per the Coastal Zone Management Plan (CZMP) of the area, the proposed Mithi Riverfront Development Project falls in Coastal Regulation Zone (CRZ) II and III. The proposal was presented to CRZ authority in its 82nd meeting on 10th June, 2013[46]. CRZ authority has not allowed any reclamation or construction activities in this stretch. For Widening, lengthening & reconstruction of the existing bridge CRZ has referred the proposal to MoEF and asked MMRDA to take prior permission of High Court if the proposal involves destruction of mangroves[47].

Observer Research Foundation, a private, not for profit organization (funded by Reliance India[48]) from Mumbai has come up with a study that recommends a 21-point programme for reclaiming the Mithi, envisaging a single and unbroken river-park corridor spanning across the entire 18-km length of the Mithi with dedicated bicycle tracks, gardens, amphitheatres, sports and recreation.[49]

Riverfront Development is NOT River Restoration

As is evident, the riverfront projects discussed above are essentially river bank beautification & Real Estate Development projects and not helping restoration of the river. The projects aim at comodifying rivers to develop urban scapes. Such riverfront development changes the essential character of the river. Stream channelization and alteration of shoreline disconnects the river stretch from adjacent ecosystems and leads to risks of habitat degradation, changes in the flow regime and siltation[50].

While the water of the rivers flows in the natural landscapes, there are many processes that are happening. Sediments are carried, fertile land is created along the banks, river channel is widened, flooding, deposition of sediments during flooding, cleansing of river etc.[51] However the urban rivers are alienated from this natural landscape to such an extent that the rivers are reduced to merely nallas carrying city’s sewage and filth.

Flow, connectivity and flood are fundamental characteristics of rivers and rivers need space for that. If these are violated the river water spreads uncontrolled through the habitation causing catastrophic events like Mithi Flooding.

Creating more room for rivers

While Indian cities are busy replicating Riverfronts of Thames and Seine, there are some remarkable projects going on in some other countries which actually talk of giving more room to the rivers during floods. They are trying to restore the river and not beautify, concretize, channelise or encroach on it.

In the Netherlands, such an integrated approach has been adopted for ‘Room for the River Program’[52]. The program is currently being implemented in the Dutch Rhine River Basin of the country.

The programme started in 2006 is scheduled to be completed by 2015. The objectives of the programme are improving safety against flooding of riverine areas of Rivers Rhine and Meuse by increasing the discharge capacity and improving of spatial quality of the riverine area.

At 39 locations, measures will be taken to give the river space to flood safely through flood bypasses, excavation of flood plains, dike relocation and lowering of groynes etc. Moreover, the measures will be designed in such a way that they improve the quality of the immediate surroundings.

While Room for the River programme focuses on flood management in sustainable way, Yolo Bypass is another unique initiative aimed at keeping intact the benefits to the ecosystem without causing a negative impact on water supply[53]. The Yolo Bypass is a flood bypass in the Sacramento Valley located in Yolo and Solano Counties of California State in USA. The primary function of the bypass is flood damage reduction. It is a designated floodway that encompasses 60,000 acres in eastern Yolo County between the cities of Davis and Sacramento. All the properties within the bypass are subject to a flood easement that allows the state to flood the land for public safety and ecological benefit.

Conclusion

Riverfront of Thames in London and Seine in Paris are often cited as successful models of riverfront development in India. However, the ecological as well as social setting of Indian rivers and the challenges that we face are significantly different from these foreign models. A Blind replication will only be wastage of public funds and degradation of the rivers further. Riverfront development projects across the country seem to be alienated from the river, and talk only about its urban banks, trying to achieve cosmetic changes on deeper wounds by encroachment and real estate development on the belly of the rivers. The need of the hour is river rejuvenation and not river FRONT development. Let us hope that we see central place for rivers in all these projects. Moreover, there is neither any social or environmental impact assessment, nor any regulation or democratic participatory decision making process. Such projects will only be at the cost of the poor, the environment, future generation and to short term benefits of real estate developers and a section of urban middle class.

Amruta Pradhan, SANDRP (With Inputs from Himanshu Thakkar & Parineeta Dandekar)

amrutapradhan@gmail.com

An edited version of this article has been published at: http://indiatogether.org/gujarat-sabarmati-riverfront-development-model-for-ganga-yamuna-environment

END NOTES:

[1] http://www.egovamc.com/SRFDCL/SRFDCL.pdf

[2] http://www.egovamc.com/SRFDCL/SRFDCL.pdf

[3] http://www.frontline.in/static/html/fl2802/stories/20110128280208500.htm

[4] http://www.frontline.in/static/html/fl2802/stories/20110128280208500.htm

[5]http://www.business-standard.com/article/current-affairs/amc-bets-on-huge-returns-from-riverfront-property-sale-114032000894_1.html

[6] http://indiaenvironmentportal.org.in/files/file/Sabarmati%20Riverfront.pdf

[7] http://www.egovamc.com/SRFDCL/SRFDCL.pdf

[8] http://indiaenvironmentportal.org.in/files/file/Sabarmati%20Riverfront.pdf

[9] http://www.downtoearth.org.in/node/5786

[10] http://www.frontline.in/static/html/fl2802/stories/20110128280208500.htm

[11] http://landscapeindiapbb.wordpress.com/2013/10/30/riverfront-development-ahmedabad/

[12] http://www.downtoearth.org.in/node/5786

[13] http://archive.indianexpress.com/news/flood-control-in-sabarmati-a-challenge-for-amc/654704/

[14] http://www.downtoearth.org.in/node/5786

[15] http://archive.indianexpress.com/news/flood-control-in-sabarmati-a-challenge-for-amc/654704/

[16] http://indiaenvironmentportal.org.in/files/file/Sabarmati%20Riverfront.pdf

[17] http://www.downtoearth.org.in/node/5786

[18] http://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/delhi/Delhi-babu-all-praise-for-Sabarmati-plan/articleshow/36363896.cms

[19] http://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/delhi/Scientist-cautions-against-riverfront-plan/articleshow/38500711.cms

[20]http://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/delhi/River-experts-say-Sabarmati-no-model-for-Yamuna/articleshow/36222968.cms

[21] http://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/delhi/Scientist-cautions-against-riverfront-plan/articleshow/38500711.cms

[22]http://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/delhi/Scientist-opposes-Sabarmati-model-says-reclaiming-floodplain-not-a-good-idea-for-Yamuna/articleshow/36679502.cms

[23] http://www.newindianexpress.com/nation/Yamuna-Action-Plan-Soon-Promises-MoEF/2013/12/19/article1953318.ece,

http://www.indiaenvironmentportal.org.in/files/Yamuna%20River%20Front%20NGT%2018Dec2013.pdf

[24]http://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/delhi/River-experts-say-Sabarmati-no-model-for-Yamuna/articleshow/36222968.cms

[25] http://www.asianage.com/delhi/illegal-colonies-near-river-may-be-shifted-946

[26] http://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/noida/Twin-cities-to-go-ahead-with-riverfront-project/articleshow/34845006.cms

[27] http://indianexpress.com/article/india/politics/modi-assigns-task-of-cleaning-ganga-to-uma-bharti/,

http://www.firstpost.com/politics/cleaning-up-the-ganga-yamuna-why-modi-must-forget-sabarmati-model-1560939.html

[28]http://www.hindustantimes.com/india-news/clean-up-act-superbody-headed-by-pm-modi-to-drive-mission-ganga/article1-1253158.aspx

[29] http://www.firstpost.com/politics/cleaning-up-the-ganga-yamuna-why-modi-must-forget-sabarmati-model-1560939.html

[30] http://news.oneindia.in/india/sabarmati-model-not-enough-for-ganga-1478033.html

[31] http://news.oneindia.in/india/sabarmati-model-not-enough-for-ganga-1478033.html

[32] http://www.business-standard.com/article/opinion/rejuvenating-a-river-114052801804_1.html

[33] http://www.business-standard.com/article/opinion/rejuvenating-a-river-114052801804_1.html

[34] http://www.assamtribune.com/scripts/detailsnew.asp?id=aug3113/city05

[35] http://guwahatilife.blogspot.in/2011/02/cm-lays-foundation-of-beautification-of.html

[36] http://www.assamtribune.com/scripts/detailsnew.asp?id=aug3113/city05

[37] http://www.psda.in/guwahati.asp

[38] http://www.ndtv.com/article/india/flash-floods-in-guwahati-seven-dead-in-last-15-hours-548974

[39] http://www.assamtribune.com/scripts/detailsnew.asp?id=aug3113/city05

[40]http://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/lucknow/Lucknow-Development-Authority-to-get-new-blueprint-of-Gomti-riverfront-development-project/articleshow/19687344.cms

http://m.financialexpress.com/news/akhilesh-wants-london-eye-in-lucknow/975999/

[41] http://www.reliancefoundation.org/urban_renewal.html

[42]http://articles.economictimes.indiatimes.com/2013-09-20/news/42252355_1_goda-park-project-reliance-foundation-mns-chief-raj-thackeray

[43] The Mumbai airport has its domestic and international terminals, and its cargo complex along the Mithi River. There are five major railway stations along the Mithi River including Mahim and Bandra on the western line andSion, Chunnabhatti and Kurla on the central line. The upcoming V ersova-Andheri-Ghatkopar corridor of the Mumbai Metro project that also crosses over the Mithi River has two stations planned along the Mithi River at Marol and Saki Naka. There are also several bus stops located close to the river all along its banks.

(Source: http://orfonline.org/cms/sites/orfonline/modules/report/ReportDetail.html?cmaid=23400&mmacmaid=23401)

[44] http://orfonline.org/cms/sites/orfonline/modules/report/ReportDetail.html?cmaid=23400&mmacmaid=23401

[45] http://indianexpress.com/article/cities/mumbai/beautification-plans-of-mithi-river-promenade-stuck-over-crz-norms/

[46] https://mczma.maharashtra.gov.in/pdf/MCZMA_MoM82.pdf

[47] The proposal was cleared subject to compliance of following conditions

(i) The proposed construction should be carried out strictly as per the provisions of CRZ Notification, 2011 (as amended from time to time) and guidelines/ clarifications given by MoEF time to time.

(ii) Disposal of debris during construction phase should be as per MSW (M&H) rules. 2000.

(iii) Tidal flow of river should not be obstructed.

(iv) The project proponent should obtain prior High Court permission, if the proposal involves destruction of mangroves or construction falls with 50 nil buffer zone.

(v) All other required permissions from different statutory authorities should be obtained prior to commencement of work

[48] http://www.rediff.com/news/report/najeeb-jung-the-man-who-may-run-delhi/20131213.htm

[49]http://www.indiawaterportal.org/sites/indiawaterportal.org/files/why_mumbai_must_reclaim_its_mithi_gautam_kirtane_orf_2011.pdf

[50] http://water.epa.gov/type/wetlands/restore/principles.cfm

[51] Nature Conservation by Ketki Ghate, Manasi Karandikar

[52] http://www.downtoearth.org.in/node/5786

[53] http://www.americanrivers.org/initiative/floods/projects/yolo-bypass-and-the-fremont-weir/

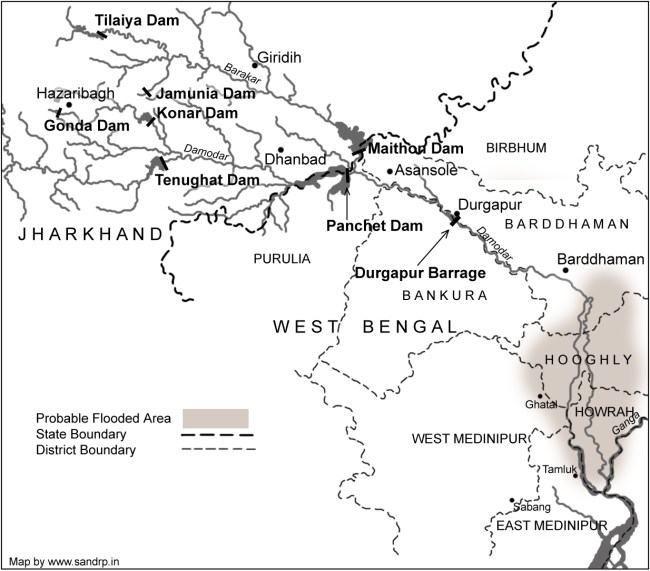

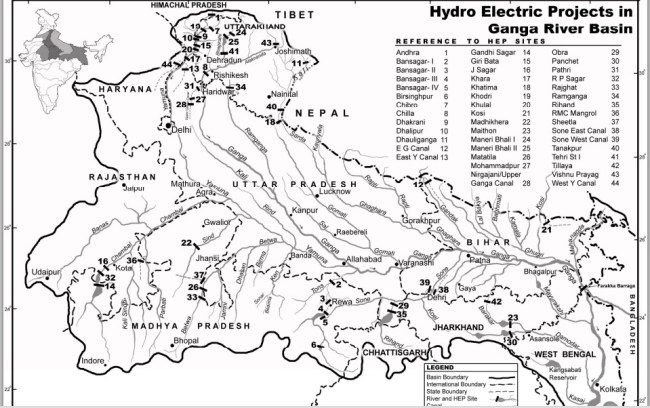

Farakka has profoundly changed the character, sediment regime and flow of Ganga. It is affecting lives of lakhs of people in India and Bangladesh through cycles of erosion, sedimentation, floods and affected fishing. Our response to the issue has been dismal. We have not conducted a single review of costs, benefits and impacts of Farakka Project so far. In addition to Farakka , Lower Ganga (Narora), Middle Ganga, Upper Ganga Barrages (Bhimgoda), Kanpur Barrage, Hydropower projects in Uttarakhand and other upstream states have affected the river in most profound ways. If we want to rejuvenate the Ganga, we need to institute a credible independent review the existing Barrages, not plan new ones. May be we can begin with a demand for such a review for Farakka on urgent basis. One World Rivers Day, let us wish for a long and healthy flow for the Ganga River, a symbol of all flowing rivers in India!

Farakka has profoundly changed the character, sediment regime and flow of Ganga. It is affecting lives of lakhs of people in India and Bangladesh through cycles of erosion, sedimentation, floods and affected fishing. Our response to the issue has been dismal. We have not conducted a single review of costs, benefits and impacts of Farakka Project so far. In addition to Farakka , Lower Ganga (Narora), Middle Ganga, Upper Ganga Barrages (Bhimgoda), Kanpur Barrage, Hydropower projects in Uttarakhand and other upstream states have affected the river in most profound ways. If we want to rejuvenate the Ganga, we need to institute a credible independent review the existing Barrages, not plan new ones. May be we can begin with a demand for such a review for Farakka on urgent basis. One World Rivers Day, let us wish for a long and healthy flow for the Ganga River, a symbol of all flowing rivers in India!