Discussions on Interlinking of Rivers are gaining momentum as new government takes charge at the centre. It is predicted that the new government will be supportive of ecologically and socially questionable plan of interlinking rivers. In this backdrop, it will be interesting to study the fate of a little known scheme of diverting west flowing water to the Godavari Basin in Maharashtra. While the entire ‘grand’ plan includes many such schemes, we are focusing on one of the biggest interbasin diversion project under this scheme. Manjarpada Phase I project which is on a shared basin between Maharashtra and Gujarat, located in the Dindori Taluka of Nashik District. We also look at the status of about 28 interbasin diversion schemes proposed and under construction in this region, their justifications, benefits as well as impacts.

Discussions on Interlinking of Rivers are gaining momentum as new government takes charge at the centre. It is predicted that the new government will be supportive of ecologically and socially questionable plan of interlinking rivers. In this backdrop, it will be interesting to study the fate of a little known scheme of diverting west flowing water to the Godavari Basin in Maharashtra. While the entire ‘grand’ plan includes many such schemes, we are focusing on one of the biggest interbasin diversion project under this scheme. Manjarpada Phase I project which is on a shared basin between Maharashtra and Gujarat, located in the Dindori Taluka of Nashik District. We also look at the status of about 28 interbasin diversion schemes proposed and under construction in this region, their justifications, benefits as well as impacts.

- Manjarpada Phase I under Upper Godavari Irrigation Project

Manjarpada Phase I forms part of the Upper Godavari Irrigation Project under the Water Resources Department, Maharashtra. The original proposal of the Upper Godavari Irrigation Project included Dams like Waghad, Karanjvan, Palkhed and Ozarkhed, which received administrative sanction in 1966. Work was started in 1968. From here on a number of components like Punegaon Dam, Tisgaon Dam, several canals kept getting added to the scheme. However, it remained essentially an intra basin project, there was no inter linking rivers component here.

In 2008 a radically different component was added to Upper Godavari Project. This was the inclusion of 12 diversion weirs on Paar, Taar, Damanganga Basin Rivers that in normal course would flow into Gujarat. These weirs envisaged near the ridge line, transferring waters of these into dams built in the Godavari Basin, via deep canals across the Western Ghats, which will transfer water from west flowing rivers to the east flowing Godavari. According to the White Paper on Irrigation Projects brought out by the Water Resources Department of Maharashtra in December 2012, these diversion weirs and Manjarpada Phase I scheme added an irrigation potential of about 30,000 hectares in the Upper Godavari Projects. The total irrigation potential of the entire Upper Godavari projects is estimated as 74,000 hectares (including 30,000 hectares from Diversion projects), of which potential of 69000 hectares is claimed to be created. This is unbelievable as the Diversion weirs, with a total command of 30,000 hectares, are just about half complete. The White Paper states that about 55% work on Manjarpada project and about 60% work on 11 diversion weirs has been completed.

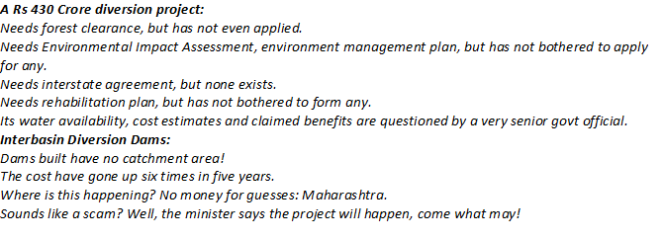

An interbasin transfer scheme that claims a cumulative irrigation potential of 30,000 hectares will have significant impact on ecosystems, communities and downstream hydrology. But no such studies have been conducted for these projects, there has been no public consultation process and it is not even known if there is any interstate agreement for this transfer. The most striking example is Manjarpada Phase I project which envisages transferring about 500 million cubic feet (Mcft) from the Paar basin into Punegaon dam in the Godavari basin by way of a dam and two significantly big tunnels. Officials of Water Resource Department have stated that the project, submerging 95 hectares of land, also needs Forest Clearance for 65 ha forest land, which has not been granted yet, although work is in an advanced stage! This is clearly illegal as per the Forest Conservation Act (1980).

SANDRP’s visit to Manjarapada Phase I Project When we visited the site of Manjarpada project, we were first struck by the name. The project has nothing to do with Manjarpada village, but is entirely based in Devsale Village of Dindori Taluk. Work on the main dam has been stopped for many months now. The villagers say that this is due to local protests, while the officials claim this is due to paucity of funds.

No impact assessment of the project has taken place. When we visited Devsale village, we were mobbed by villagers who wanted to show us the damages caused by the project for which they have received no compensations. The incessant blasting of the tunnel in the hardrock has resulted in cracks to many homes. More than 250 villagers claim that they have lost water from their shallow wells/ bore wells. More than 50 well owners have submitted a memorandum to the Collector and Zilla Parishad office about drying up of their wells.

Above: Manjarpada Dam wall under construction. Photo: Amit Tillu for SANDRP

The villagers indicate 2 tunnels under construction for the same project, one of which is complete in 1 km length and the other complete in nearly 8 km length, with a huge air vent 20 m wide and over 150 m deep. The depth of the tunnel underground is about 150-300 feet.

Above: Under construction tunnel at Manjarpada Phase I Photo: Amit Tillu for SANDRP

The laborers employed by the subcontractor do not understand Marathi and cannot respond to questions asked by the villagers. Work on the main dam wall has stopped since the last 2 years. Villagers say that blasting and tunneling has severely affected groundwater in the region, which has fallen drastically after tunneling. Blasting has resulted in not only cracks in over 100 homes, it has led to collapse of more than 10 built open wells, turning them into puddles. This was witnessed by us. Displaced families have not been resettled[1] yet.

Corruption involved in the unfeasible Manjarpada Project: Whistle-blower of the Water Resources Department Vijay Pandhare has been highlighting issues about Manjarpada project since a long time, when he was in service as Chief Engineer at Maharashtra Engineering Training Academy. He had pointed serious irregularities about this project in his letters to the Secretary, Maharashtra Water Resource Department, state Chief Minister Prithviraj Chavan as well as separately to Dr. Chitale who was supposed to be investigating the Maharashtra dam scam.

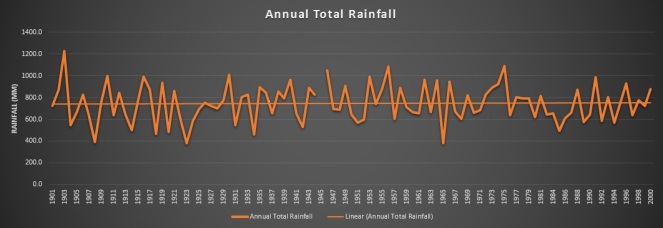

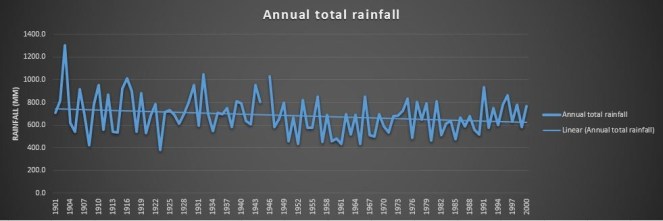

Pandhare talked exclusively with SANDRP on Manjarapada Project, he said: “This project is planned to transfer about 500 million cubic feet of water and is costing about Rs 500 crores and these estimates will increase. It should have costed a fraction of this. The entire process of Manjarapada Phase 1 was driven by the politician and contractor lobby and there was never any space for rational questioning. In addition to Manjarpada Stage I, the department is now also pushing for Manjarpada phase II downstream of this project, which will divert water right into the Tapi Basin. Now the catchment area of Manjarpada Phase I and Phase II actually overlap and the projects are simply unfeasible as there is no water availability as stated in the water availability certificates. This needs to be thoroughly investigated and I had written about this to many authorities, in vain.”

Shri. Pandhare is justified in raising these issues. If we look at the internal note of MID, with SANDRP, it states that in 2008 Manjarapada project was approved Rs. 62.54 Crores. Till December 2013, Rs 122.66 Crores were spent on this project! This has resulted in 30% work on spillway, 80% on connecting tunnel, 100% on open canal, 72% on diversion tunnel.

The last line on the project drops a bomb. It states: “An estimate for Third administrative approval for Upper Godavari Project, which includes the cost of this project at Rs 430.74 crores for Manjarpada project, has been presented before the government for approval.” So within 5 years, cost of the project shot up nearly 6 folds!

Above: One of the several open wells collapsed due to balsting for Manjarpada project Photo: Amit Tillu for SANDRP

Above: One of the several open wells collapsed due to balsting for Manjarpada project Photo: Amit Tillu for SANDRP

Pandhare writes in his letter to the Secretary and Chief Minister, the letter that initially shook the water management circles in Maharashtra[2]. “The system that makes cost estimates in WRD is has been nearly killed. So the field officer has been made in-charge of working on estimates. In reality the contractor makes these estimates and they are sanctioned without checking. Otherwise such unfeasible and costly work would not be undertaken… In case of Manjrapada project, the cost estimates, especially tunnel excavation costs have been bloated beyond measure. The benefits are hazy. When Phase I is questionable, unfeasible and hugely costly Manjrpada II is being pushed by political backing. This project has a water availability certificate, when in fact the catchment does not have enough water.” He has specifically requested Dr. Chitale to investigate this project.[3]

When we met the Executive Engineer, MI Projects (Local Sector), for Nashik division, he agreed that there is controversy surrounding Manjarpada Projects, especially related to feasibility and overlap of catchment area, but refused to comment further. He softly added that political interference with water resource department should reduce. In the meantime, Chagan Bhujbal, former MP from Nashik region (he lost in 2014 Parliamentary elections by huge margin of close to 2 lakh votes) has been stating that Manjrapada II will happen at any cost.[4]

One of the official stated that Manjarpada project is the ‘Boss’ of these schemes as it will route water from many schemes in the Paar Basin into the Godavari Basin. Though he later added that the main reason for pushing Manjarpada was that the Punegaon Dam, downstream Manjarpada has not been filling up in monsoon and Manjarpada will aid it. This again underlines Pandhare’s claim that water availability certificates being given for projects in Maharashtra (like Punegaon) are not scientific and driven by other motives!

Above: Villagers at Devsale talking about issues of Manjarpada Project I Photo: Amit Tillu for SANDRP

Incidentally, according to white paper, it’s interesting to see the list of water users downstream of these projects. They include Ranwad sugar factory, K Distillery, Ashokumar Hatcheries, Everest Industries, Seagram Distillery, Shivam chemical, Kadwa Sugar industry, Dinodri MIDC (which is a Wine MIDC in Maharashtra) & have a reservation on 136 MCFt. While Manmad taluka suffered acute water stress in drought in 2012-13, water supply to distilleries and wine industries continued.

This whole episode involving the project, its decision making process, lack of impact assessment and credible techno-economic appraisal and monitoring raises many questions. In the first place, the Manjarpada project highlights the need for thorough participatory processes that should be undertaken before taking up such projects, especially when they involve interbasin transfers.

Maharashtra and Gujarat have signed an MoU to transfer waters from Damanganga River into Vaitarna basin through Bhugad, Khargihill and Pinjal Dams and tunnel systems. The tunnel envisaged between Pinjal and Khargihill stretches over 64 kilometers, more than 5 times the tunnel in Manjarada. It is clear that the impacts of not only the dams, but the tunnel systems will be huge and need investigation.

More than 19 Diversion Projects diverting “unutilized water going waste to the Arabian Sea”

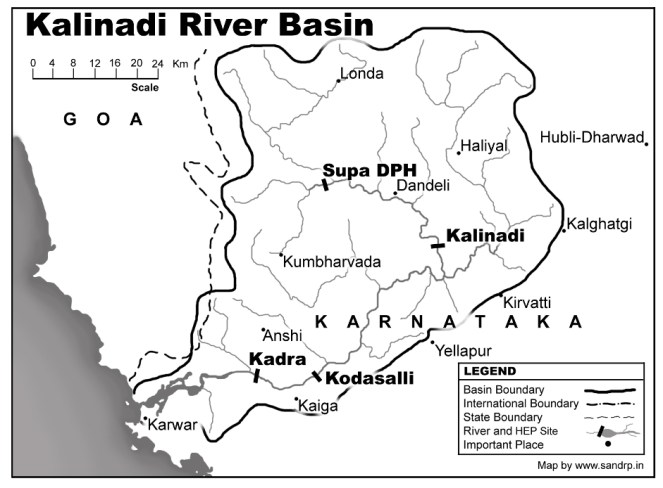

When we met officials at the Minor Irrigation Division (MID), they showed us the map of intricate links planned in the entire Damangagang, Paar, Naar Basin as well as parts of Vaitarna and Ulhas basin to transfer water “flowing unutilized to the Arabian Sea” into the Godavari Basin. It is difficult to imagine that a project of this massive scale, which can transfer nearly 400 MCM from West Flowing basins into the Godavari basin is going on without any project specific impact assessment, cumulative impact assessment, cost benefit studies, environmental appraisal, environment management plan, public consultations, environmental monitoring and based on questionable water availability studies.

The Maharashtra Irrigation Dept GR dated Sept 2005 approved the proposal of diversion schemes near the ridge line to divert water which was “going waste, unutilised into the Arabian Sea” to Godavari Basin in the East. 19 such schemes have received approval from the Hydrology Project (Jal Vgyan Prakalpa) Nashik. Of these 19 schemes, 13 have been included in the second administrative approval of the Upper Godavari Project, but there are in all nearly 28 diversion schemes under consideration. Table in Annexure 1 provides details of the various schemes under this project.

Above: Diversion Weirs at Dindori, with deep canal on the upstream transferring water Photo: Parineeta Dandekar, SANDRP

SANDRP team also visited some of these diversion weirs.

In case of Amboli Diversion Weir, its capacity is supposed to be close to 1 MCM (million cubic meters). It was bone dry in May when SANDRP team visited it. Sagar Marathe, who resides next to the weir states that the weir, now complete, hardly holds any water in it. The reason seems obvious. Just 200-300 mts upstream the dam wall, a high canal embankment runs, which means that the dam has nearly no catchment area! There is no study on the amount of water that is indeed diverted into Kashyapi River here, a tributary of Godavari.

Above: Dam wall and the dry Amoboli Diversion Weir reservoir can be seen on the left, on the right is a tall embankment of an older canal which runs parallel to the dam wall and is much longer. Effectively, the dam has nearly no catchment. Photo: Parineeta Dandekar

In case of Waghera diversion weir, which is supposed to be under construction, the tribal villagers told SANDRP that the mud dam has been existing since the past 20-25 years and the only work going on is digging the canals! But the MID note does not state that the dam is already existing, possibly indicating an irregularity.

These examples are only indicative. They highlight the need for transparent and participatory studies surrounding these projects.

Above: Unlined canal in Dindori, transferring water onto Waghad Dam. Photo: Parineeta Dandekar, SANDRP

Environment laws violated, but MoEF in dark and inactive! Manjarpada Diversion and other diversion dam projects are coming up in violation of the EIA Notification 2006, but MoEF seems to know nothing about it. Manjarpada or other diversion schemes cannot claim exclusion from the environmental appraisal process since it involves huge irrigation, in addition to inter basin transfer, domestic & industrial water supply.

The entire diversion scheme raises big questions about significant impacts, needs of the downstream population, local opposition and finally questionable and unassessed benefits. We hope MoEF will take cognizance of the legal violations and take stringent steps against Maharashtra government. Unfortunately Maharashtra is mired with too many of such examples, in addition to the dam scam.

– Parineeta Dandekar ( parineeta.dandekar@gmail.com), Amit Tillu ( amittillu@gmail.com) with inputs from Himanshu Thakkar ( ht.sandrp@gmail.com)

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Annexure 1

Table 1 Overview of Interbasin diversion projects planned to divert water into the Godavari Basin.

| Name | Basin | Basin in which water is transferred | Quantity | Remark | |||

| Manjarpada Diversion Project Nashik | Par | Godavari: Punegaon and Karanjvan Dams | 17.16 MCM | ||||

| Golshi Mahaji Flow Diversion Project, Dindori | Damanganga origin 10 nallahs to be diverted | Waghad Dam, Godavari | 0.47 MCMto be transferred | Current cost around 32 Crores( 12.97 spent, 21.31 requested) | |||

| Nanashi Flow Diversion Project, DindoriNashik | Nar-Par. Dam at the origin of Par, from here to Hattipada DW, from there to Karanjvan Dam | Karanjvan Dam, Godavari | 1 MCM into Godavari 0.55 MCM for local use | Initial estimate was 3.04 crores in 2008. Actually 3.81 crores spent, Now application for 17.1 crores made for 3rd administrative approval | |||

| 4. | Golshi 1, Flow Diversion Project, Dindori Dindori | Damanganga Basin | Waghad Dam | 3.11 MCM | 1.29 crores in 2008.3.15 crores asked in 3rd administrative approval | ||

| 5. | Hatti pada, Flow Diversion Project, Dindori DindoriNashik | Paar Basin | Karanjvan dam, Godavari Basin | 0.93 mcm to Karanjvan Dam. 0.67 mcm for local use | 3.11 crores in 2008, 7.64 crores spent till Dec 2013, now requested: 14.24 crores in 3rd approval | ||

| 6. | Dhondalpada Flow Diversion Project | NA | Godavari basin | 1.73 MCM Consists of5 saddle dams | |||

| 7. | Chaphyacha pada | Na | Godavari | 0.30 MCM | |||

| Ranpada Diversion project | NA | Godavari | 0.35 MCM | ||||

| Payarpada Flow Diversion Canal, Dindori Nashik | NA | Godavari | 2.039 MCM | Local opposition to Land aquisition. Hence work not started. | |||

| Ambaad Diversion canal. Dindori Nashik | 0.40 MCM | Local opposition to land acquisition. Work not started | |||||

| Pimpraj F diversion Project | NA | Godavari | 1.26 MCM | ||||

| Ambegan F Diversion Prjct | NA | Godavari | 1.40 MCM | ||||

| Jharlipada F Diversion Prct | Waghad Dam, Godavari Basin | 1.05 MCM | |||||

| Chimanpada Flow Diversion Project Dindori | Godavari | 0.83 MCM for diversion; 0.45 MCM for local use, | No technical Sanction yet | ||||

| Waghera Flow Diversion Scheme, TrimbakNashik | Damanganga Basin | Godavari ( no dam, u/s of Ganga pur Dam) | 1.19 MCM | Sanctioned cost in 2007 was 15 crores. 80% work complete, Link cut work under progress | |||

| Pegal wadi Flow Diversion Project, Trimbak, Nashik | Vaitarna Basin | Godavari | 0.695 MCM | In 2004, 17.92 crores approved | |||

| Amboli (Bombiltekpada) | Godavari | 0.92 MCM | 17.92 Cr approved in 2004 (an error?) | ||||

| Total | 34.83 MCM | ||||||

| Schemes which do not have administrative approval, but are included in the Upper Godavari Project by the Godavari Irrigation Development Corp. | |||||||

| Velunje-Amboli Dvrsn Prjct | Damanganga | Godavari | 1.447 MCM | 16.07 crores estimated | |||

| Kalmuste Diversion project | Damanganga | Godavari | 23.141 MCM by a diversion weir | 333 Crores estimated price | |||

| 3. | Kapwadi Diversion Project | Ulhas | Godavari | 7.04 MCM | Estimated cost 60.8 Cr | ||

| Sub Total | 31.62 MCM | ||||||

| Projects with survey permissions and administrative approval | |||||||

| Lift dvrsn prjct 3, Surgana | Paar | Godavari | 94.37 MCM | ||||

| Lift dvrsn prjct 4, Surgana | Paar | Godavari | 89.12 MCM | ||||

| Sub Total | 183.49 MCM | ||||||

| Water Diversion from Upper Vaitarna Basin to Godavari Basin | |||||||

| Note: GOM approved the scheme to fit doors to the saddle dam of Vaitarna project and transfer water into Godavari. However, Thane Circle of KIDC had acquired 4689 hectares of Upper Vaitarna Project. Eventually, Dam height was reduced and 623 hectares was additional land left which should have been returned to the PAPs. But this was not done. There is a strong opposition of local people to any survey without this return. No has been conducted as yet. | 28.50 MCM. | ||||||

| 6 Diversion projects for Ahmednagar under very primary planning | |||||||

| Hivra Walvani Diversion Weir | Pravara | 18.46 MCM | 13 hectares forest land | ||||

| Samrand Diversion weir | Pravara | 17.98 MCM | 6 hectares forest land bot fall in PA. Hydrology Project communicated that the project is not supported by the GOM. CE, KIDC has written in 2012 that there is no water to transfer to the east. | ||||

| Sub Total | 36.44 MCM | ||||||

| Transfer water from Shai and Kalu Basins into Akole between Harishchandragad and Ajoba Mountain into Mula basin | |||||||

| Tolarkhind Tunnel Project | 18.08 MCM | CE, KIDC has written in 2012 that no surplus water available in Shai & Kalu Basins for dvrsion. | |||||

| Khirehwarer Tunnel Prject | 40.01 MCM | ||||||

| Sadada Tunnel Project | 11.13 MCM | ||||||

| Pathar Ghat dvrsn canal pr | 7.67 MCM | ||||||

| Diverion from Kalu and Shai Basin | 76.89 MCM | ||||||

| TOTAL PLANNED DIVERISON FROM WEST TO EAST in Godavari Basin | 391.77 MCM | ||||||

Source: Minor Irrigation Department, Nashik Division

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

END NOTES:

[2] https://sandrp.in/irrigation/Letter_Maharashtra_Irrigation_Scam_Oct12.pdf