Union Finance Minister Arun Jaitley’s Maiden Full year budget presented to the Parliament on Feb 28, 2015 invited a lot of hype. Let us see what his statement of account for the 2015-16 has in store for rivers, environment, Himalayas, farmers, Climate Victims or sustainable water resources development. Continue reading “India Budget 2015: Is there any hope for rivers, environment or farmers?”

Tag: Ganga

Ekti Nadir Naam: Ramblings through the etymology of River names in India

Above: Dry Chandrabhaga from Maharashtra. We have at least 5 Chandrabhagas in India! Photo: Parineeta Dandekar

~~

“I’m going to buy vegetables from the banks of Ganga. Coming?” (“गंगेवर चालले आहे भाजी आणायला. येणार?”). This was my Grandmother’s Sunday morning ritual. I always jumped at the opportunity: it meant going to the local market skirting Ganga and staring at colorful heaps of vegetables, patting dewlaps of humongous cows settled in islands, stealing guilty glances at sadhus who sold fascinating stuff: owl claws, deer musk pods, Giant Entada seeds..but most of all, it meant observing the filthy and beautiful river from the Ghats. I lived in Nashik, on the banks of Godavari and Godavari was our Ganga. Continue reading “Ekti Nadir Naam: Ramblings through the etymology of River names in India”

An Epic Voyage along the Ganga comes to close!

From Burton and Speke’s expedition to the origin of Nile to the age old Narmada Parikrama or the Chaar Dhaam Yatras (which are as much river journeys as pilgrimages), River journeys have always enthralled travelers and listeners alike. Continue reading “An Epic Voyage along the Ganga comes to close!”

Headwater Extinctions by Emmanuel Theophilus: SOME CONCERNS

By Prof Prakash Nautiyal, (lotic.biodiversity@gmail.com) HNB Garhwal University, Srinagar, Uttarakhand

I have gone through the report Headwater extinctions: Hydropower projects in the Himalayan reaches of the Ganga and the Beas: A closer look at impacts on fish and river ecosystems by Emmanuel Theophilus[1], published by SANDRP, thanks for sending the report to me in hard and soft copy. It is indeed excellent, many more pages can be written on the beautiful portrayal. I am flagging some concerns, in context of the whole issue. Continue reading “Headwater Extinctions by Emmanuel Theophilus: SOME CONCERNS”

Rivers in the News during 2014

Above: The beautiful Lohit River, Arunachal Pradesh Photo: Arati Kumar Rao (http://riverdiaries.tumblr.com/)

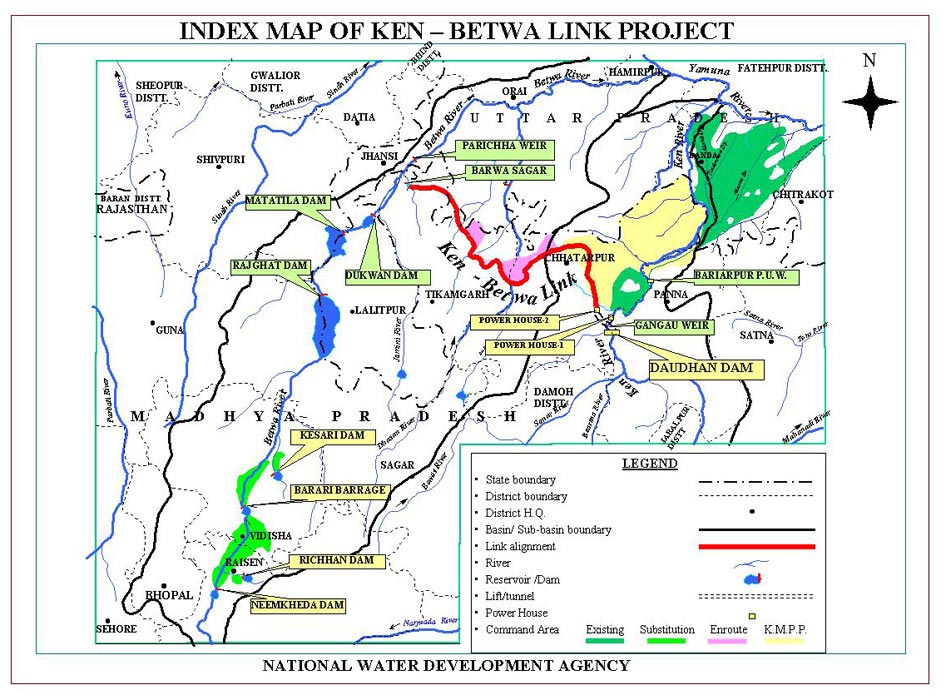

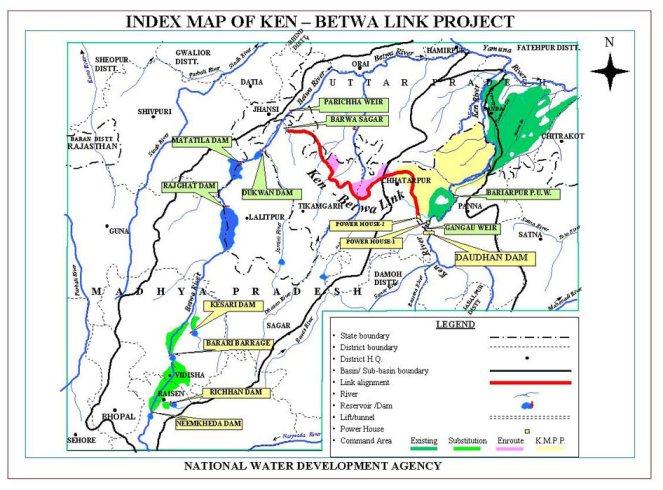

Violations in Ken Betwa Riverlink Public Hearings in last week of 2014

The public hearings required for the Ken Betwa River linking project (KBRLP) are to be held on Dec 23 and 27, 2014 at Silon in Chhattarpur and Hinouta in Panna districts of Madhya Pradesh. However, these public hearings violate fundamental legal norms in letter and spirit and should be cancelled and not held till these violations are rectified.

Firstly, the EIA (Environment Impact Assessment) notification of September 2006 clearly states that project EIA and EMP (Environment Management Plan) should be put up on the website of the Pollution Control Board a month before the actual public hearing. However, a perusal of the MPPCB website (http://www.mppcb.nic.in/) shows that the full EIA and EMP are still not uploaded on the website. When I talked with the concerned officers of the MPPCB, they confirmed that full EIA-EMP reports have NOT been uploaded on the MPPCB website.

Secondly, even the executive summary of EIA-EMP Report on the website is put up in such an obscure fashion that it is not possible for any common person to locate it. So I called up the phone number given on the MPPCB website: 0755-2464428. I was then told that I should call 0755 2466735 to talk to Mr Kuswaha about this. When I called Mr Kuswaha, he directed me to call Mr Manoj Kumar (09300770803). Mr. Manoj Kumar told me at 5.15 pm on Thursday, Dec 18 that he was already home and that I should call him at 12 noon next day. He however, confessed that even the executive summaries were not there about 15 days ago! When I called Mr Manoj Kumar next day and succeeded in connecting only after a few attempts, he told me that I need to first click on “Public Hearing” tab (Under EIA notification). On clicking this, one goes to a page with a table displaying various lists entitled List 1, List II, List III and List IV etc. Then one needs to click List IV. On clicking that one will see a list of projects from 469 to 601 and in that you go to project no 594 which is the Ken Betwa Project. There is no mention of the date of Public Hearing here.

I also called up Dr R K Jain (09425452150) at MPPCB regional office in Sagar, under whose jurisdiction Chhattarpur and Panna come to ask about the availability of the full EIA and EMP in soft copies. He said they are available at designated places, but about not being available on MPPCB website and available executive summaries not being properly displayed on MPPCB websites, he said that he is unable to do anything as that is happening from Bhopal.

When I told him that it is impossible for anyone visiting the MPPCB site to find this project and that the current public hearings need to be displayed more prominently, he hung up the phone, saying he has no time to answer such questions! In any case non-display of the public hearing date and executive summary in Hindi and English in easily searchable form is another violation of the EIA notification.

Thirdly, when we go through the Executive summaries in English and Hindi, we see that both are incomplete in many fundamental ways. The Hindi executive summary[1] has completely wrong translations. I could find nine gross translation errors in just first 16 paragraphs. The Hindi translation has not bothered to translation words like monsoon, MCM, PH, LBC, CCA, FRL, MWL, K-B, tunnel in first 16 paras, nor given their full forms. This makes the Hindi translation completely incomplete, wrong and unacceptable.

Fourthly, even the English (& Hindi) version of Executive summary on MPPCB website[2] is incomplete. It does not have a project layout map, sections like options assessment and downstream impacts.

Fifthly, the EIA claims in very second paragraph: “The scope of EIA studies inter-alia does not include water balance studies.” This is a wrong claim since water balance study of the Ken Betwa links establishes the hydrological viability of the project and by not going into the water balance study, the EIA has failed to establish hydrological viability of the project. SANDRP analysis in 2005[3] of the NWDA feasibility study of Ken Betwa Proposal[4] had established that the hydrological balance study in the Feasibility of the Ken Betwa Link Project is flawed and an exercise in manipulation to show that Ken has surplus water and Betwa is deficit. As the collector of Panna district noted in 2005 itself, if the 19633 sq km catchment of the Ken river upstream of the proposed Daudhan dam (comprising areas of eight districts: Panna, Chhatarpur, Sagar, Damoh, Satna, Narsinghpur, Katni, and Raisen) were to use the local water options optimally, then there will not be any surplus seen in Ken river at the Daudhan dam site and by going ahead with the Ken Betwa Link without exhausting the water use potential of Ken catchment, which is predominantly a tribal area, the government is planning to keep this area permanently backward. But the EIA of Ken Betwa link does not even go into this issue, making the whole exercise incomplete.

Sixthly, the Ken Betwa Link project is a joint project between Uttar Pradesh (UP) and Madhya Pradesh (MP), about half of the benefits and downstream impacts in Ken and Betwa basins are to be faced by Uttar Pradesh, but the public hearings are not being conducted in UP at all, the proposed public hearing is only in MP! Even within MP, the link canals will pass through and thus affect people in Tikamgarh district, but the public hearing is not being held in Tikamgarh district either.

Seventhly, the project had applied for the legally required Terms of Reference Clearance (TORC) and the same was discussed in the meeting of Expert Appraisal Committee (EAC) on River Valley Projects of Union Ministry of Environment, Forests & Climate Change (MoEF&CC) on Dec 20, 2010. However the public hearing is being held more than four years after EAC recommended the TORC and that is way beyond the normal term of two years for which TORC is valid and even for extended term of TORC of four years. The public hearing being conducted without valid TORC can clearly not be considered valid under EIA notification and hence there is no legal validity of this public hearing.

Eighthly, the EIA done by the Agriculture Finance Corporation of India was already completed when the project applied for TORC! I know this for a fact since copies of their (most shoddy) EIA were made available to the members of the Expert Committee on Inter Linking of Rivers set up by the Union Ministry of Water Resources in Nov 2009 itself. I having been a member of the committee had critiqued the shoddy EIA in April 2010 and this was also discussed in one of the meetings where the AFC EIA consultants were called and had no answer to the questions. The same base line data that is now more than five years old is being used in the EIA being used for this public hearing! This is again in complete violation of the EIA norms.

Ninthly, in a strange development, MoEF&CC issued TORC for the project on Sept 15, 2014, following a letter from National Water Development Agency dated 18.06.2014. This letter is clearly issued in violation of the EIA notification, since as per the EIA notification, the ministry could have either issued the TORC within 60 days of Dec 20, 2010 meeting of the EAC or the TORC would be deemed to have been given on 61st day or Feb 19, 2011. However, issuing the letter almost four years after the EAC meeting and that too without mentioning the deemed clearance is clearly in violation of the EIA notification.

The TORC letter on MoEF&CC website is also incomplete as it does not mention the Terms of Reference at all! They are supposedly in the Annexure 1 mentioned in the TORC, but the letter on MoEF&CC site does not include Annexure 1. When I asked Dr B B Barman, Director of MoEF&CC and who has signed the TORC letter, he said that the project has been given standard TORs for any River Valley Project. But Dr Barman forgot that the MoEF&CC was giving the TORC for the first ever interlinking of rivers project and the TOR for this unprecedented project CANNOT be same as any other River Valley Project. The TORC letter is invalid also from this aspect.

The MoEF&CC letter of Sept 15, 2014 is also without mandate for another reason. The letter says “Based on the recommendations of the EAC, the Ministry of Environment & Forests hereby accords clearance for pre-construction activities at the proposed site as per the provisions of the Environmental Impact Assessment Notification, 2006 and its subsequent amendment, 2009”. However, MoEF&CC seems to have forgotten here that the Daudhan dam site and most of the reservoir is inside the Panna Tiger reserve. Perusal of the 45th EAC meeting held on Dec 20-21, 2010 shows that EAC did not recommend preconstruction activity and the EIA division of the MoEF&CC that issued the Sept 15 2014 has no authority to allow pre construction activities inside the protected areas like Panna Tiger Reserve. Even the NBWL (National Board of Wild Life) Standing Committee meeting of Sept 14, 2006 allowed only survey and investigation and NOT preconstruction activity and in any case such activities inside protected areas cannot be allowed without Supreme Court clearance. It is thus clear that Sept 15, 2014 letter of MoEF&CC for Ken Betwa link is also without authority.

There is a third reason why the MoEF&CC letter of Sept 15, 2014 is legally invalid: the letter giving Terms of Reference clearance did not include the conditions EAC stipulated when it recommended the TORC in the EAC meeting of Dec 20, 2010. One of the conditions was that a downstream study will be done by Central Inland Fisheries Research Institute. This becomes particularly important since there is a Ken Ghariyal Sanctuary[5] which will be affected, as also the Raneh falls, both are also tourist attractions.

However, the EIA of the Ken Betwa links has no downstream impact assessment, no mention of Ken Ghariyal Sanctuary or Raneh falls. The EIA also does not contain the CIFRI study that EAC had asked for. This is yet another reason why this incomplete and inadequate EIA cannot be basis for the public hearing from Ken Betwa Project.

This article is not a critique of the EIA of the Ken Betwa Link, I hope to write a separate article for that. Here we only see how illegal is the Public hearing for Ken Betwa link to be held during Dec 23 and 27, 2014 in Chhatarput and Panna districts. The Ken Betwa link project itself is unviable and unjustified and should not be taken up at all. But that will need another article.

It seems the current Union Government under Mr Narendra Modi and Water Resources Ministry under Sushri Uma Bharti are trying to push ahead with their River Link agenda, putting aside even legal stipulations. They also do not seem to be bothered that the Ken Betwa link will only have adverse impact on Ganga and this will also affect the Ganga Rejuvenation that they say is their priority. The EIA does not say a word on this count.

We hope the proposed public hearing will be cancelled. In any case, any clearance given to the project based on such a public hearing will remain open to challenge.

Himanshu Thakkar, SANDRP (ht.sandrp@gmail.com)

END NOTES:

[1] http://www.mppcb.nic.in/pdf/594-hindi.pdf

[2] http://www.mppcb.nic.in/pdf/594-English.pdf

[3] Ken Betwa Link: Why it won’t click: https://sandrp.in/riverlinking/knbtwalink.pdf, a Hindi translation is also available, write to SANDRP for the same.

[4] http://nwda.gov.in/index4.asp?ssslid=35&subsubsublinkid=22&langid=1

[5] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ken_River

[7] http://nwda.gov.in/index2.asp?slid=280&sublinkid=91&langid=1

[8] https://sandrp.in/riverlinking/Why_Ken_Betwa%20_EIA_is_unacceptable_April_2010.pdf, also see AFC ltd website mentioning that they got the work for doing EIA for Ken Betwa project in 2009 itself: http://afcindia.org.in/ecology_impact2.html

Lessons from Farakka as we plan more barrages on Ganga

Introduction

“When Farakka barrage was built, the engineers did not plan for such massive silt. But it has become one of the biggest problems of the barrage now” said Dr. P.K. Parua[1]. And he should know as he has been associated with the barrage for nearly 38 years and retired as the General Manager of Farakka Barrage Project (FBP). I remembered the vast island of silt in the middle of the river barely a kilometer upstream of the Barrage and the people who told us their homes were devastated by the swinging river.

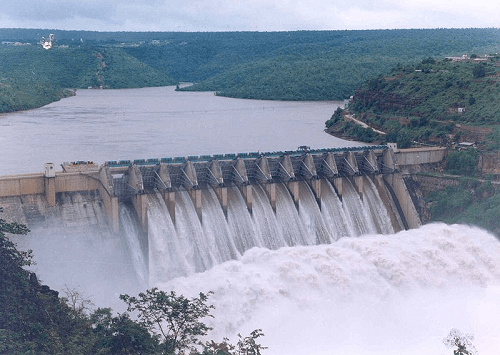

Though called a barrage, Farakka Barrage is a large dam as per ICOLD, WCD and CWC definitions, with associated large dimensions and impacts. To call it a Barrage is misleading.

Commissioned in 1975[i] across Ganga in Murshidabad District of West Bengal and just 16 kms upstream of the Bangladesh Border, Farakka Barrage has been mired in controversies from the very beginning. Its role is singular: to transfer 40,000 cusecs water from Ganga to its distributary Bhagirathi-Hooghly (hence forth referred as Hooghly). And to make Hoogly river navigable from Kolkata port upstream till Farakka barrage. It was thought that this water will push the silt that is eating up the Kolkata Port and will protect the Port for navigation and economy. In reality, Kolkata Port continues to decay and the barrage has had such severe and unforeseen impacts on the people of India and Bangladesh that the call to review Farakka Barrage entirely is getting louder by the day.

A lot has been written about Farakka Barrage by Indian (and many times by Bangladeshi) authors, so why are we discussing Farakka again? Because Political leaders like Shri. Nitin Gadkari have stated that there are plans of building a barrage after every 100 kms in Ganga from Haldia to Allahabad, a 1600 kms stretch. So we are looking at possibly 15 more barrages on Ganga. But before taking decision about building any other such structure, we need to understand the range of impacts a single barrage has had on the lives of millions of people and how inadequate has been our response in addressing these impacts. Farakka holds critical lessons for Indian politicians, policy-makers, international groups and financial institutions like World Bank dreaming of making a string of barrages across a river which has one of the highest silt loads, densest population and the largest deltas in the world.

Ganga as a “Waterway” Government of India is planning to aggressively develop 1620 kilometers of National River Ganga as “National Waterway 1” (NW1). There is a profound difference between a Highway and Waterway. A highway is simply a road while NW1 is actually River Ganga, performing several other functions, it is important to recognise how the NW1 would affect these functions and the river itself. NW 1 spans from Haldia, near the mouth of Ganga Estuary in West Bengal, to Allahabad in Uttar Pradesh, passing through four states and cities of Haldia, Howrah, Kolkata, Bhagalpur, Buxar, Patna, Ghazipur, Varanasi and Allahabad.

The Inland Waterways Authority of India (IWAI)[ii] plans to use this waterway for the transport of “coal, fly-ash, food grains, cement, stone chips, oil and over dimensional cargo.” Not surprisingly, companies keenly interested in using this waterway include “thermal power plants, cement companies, fertilizer companies, oil companies” etc. In order to make this stretch navigable, IWAI plans initiatives like “river training and conservancy, structural improvement, dredging, and Construction of terminals at Allahabad, Varansai, Gazipur in Uttar Pradesh, Sahibganj in Bihar and Katwa in West Bengal.”

Although this plan was on paper for some years, the new government has approached the World Bank for support of nearly Rs 4200 Crores (700 million dollar) for its implementation. In July 2014, the World Bank agreed to fund initial 50 million dollars including technical support (thus creating work for its own experts!). World Bank Team has already visited Patna for this project and joint meeting of IWAI and World Bank has taken place at Varanasi[iii]. No public consultation has been held thus far.

Although River Navigation has nothing to do with River Rejuvenation, Shri. Nitin Gadkari, Union Surface Transport & Shipping Minister with additional portfolio of Rural Development, who played an active role in the Ganga Manthan, announced this navigation plan as a part of ‘Ganga Rejuvenation’.[iv]

He also announced that the plan entails erecting barrages (dams) on the Ganga at every 100 kilometer interval from Haldia to Allahabad. This would mean damming the Ganga rough about 15-16 times, to maintain water levels and navigability.[v]

If the plan moves ahead, it may escape environmental clearance as the very limited EIA Notification 2006, being actively amended for dilution by the Modi government, includes only irrigation and hydropower dams in its ambit. This does not mean that these barrages will not have severe impacts on the river, its people and its ecosystems. Far from it. SANDRP has written about the impacts of Upper Ganga Barrage at Bhimgouda, the Lower Ganga Barrage at Narora and the Farakka Barrage in Murshidabad, West Bengal (SANDRP’s Report on Farakka, 1999: https://sandrp.in/dams/impct_frka_wcd.pdf).

The analysis at hand is based on official documents and research, site visit, interviews and discussions with experts and local people.

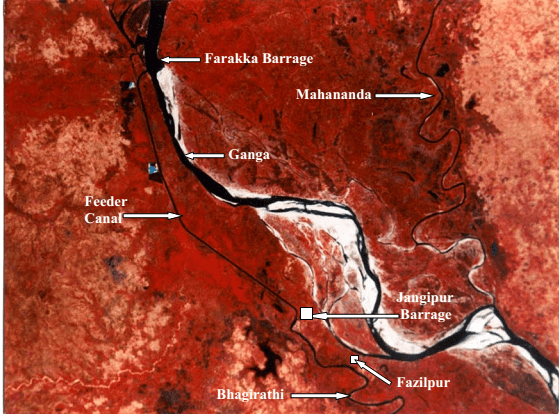

- Farakka Barrage, in the backdrop of proposed Barrages

Farakka Barrage, 2.62 kms long, commissioned in 1975 has a unique purpose. The barrage was built for diverting waters of Ganga into its distributary The Hooghly/ Bhagirtahi, for flushing sediments and maintaining the navigability of Kolkata Port (& Hooghly River) which lies at the mouth of Hooghly. Records about high sedimentation in Hooghly can be traced back to 17th Century, but is known to increase following building of Damodar Dams in post independent India. Construction of a barrage on Ganga and diverting its waters into Hooghly was suggested in the 19th Century by Sir Arthur Cotton. After independence, the historic Kolkata port was becoming hugely silted due to sluggish freshwater from upstream on the one hand and and strong saline intrusion from the sea on the other. At that time, Farakka Barrage was thought to be an answer to these problems.

Even then, some lone voices highlighted the possible impacts of Farakka Barrage. Notably Mr. Kapil Bhattacharya, Engineer-in-Chief of West Bengal had warned about absence of sufficient water, catastrophic floods and sedimentation in the upstream back in 70s. When Pakistan (current Bangladesh was part of Pakistan during 1947-1971) upheld his views, he was branded as a traitor and lost his job. He had highlighted that one of the main reasons why Hooghly was desiccating was Damodar Valley Corporation (DVC) dams on Damodar and Roopnarayan Rivers.

The Farakka Barrage completed in 1975 has 109 gates, and a feeder canal of 38.1 kms emanating from the right bank, carrying water from Ganga to Hooghly. There is one more barrage at Jangipur in the downstream and afflux bunds in the upstream of Farakka, diverting waters of all smaller rivers like Pagla and Choto Bhagirathi into Farakka, effectively drying them in the downstream.

The Feeder canal is supposed to divert 40,000 cusecs water continuously from Ganga into Bhagirathi/ Hooghly. Hooghly-Bhagirathi itself is not a small river. It is a system drained by 7 tributaries like Pagla, Bansloi, Mayurakshi, Ajoy, Damodar, Rupnarayan, Haldi and the two offshoots of Ganga – Jalangi and Churni.

- Impacts and performance of Farakka Barrage

Several grave questions are being posed on the utility of the barrage itself and its impacts. Some of the main points are illustrated below:

- Hooghly estuary cannot be made silt-free by 40,000 cusecs from Farakka only

River Expert Dr. Kalyan Rudra, an authority on rivers in Bengal, especially their interactions with sediment, says that the initial objective of Farakka of flushing silt from the mouth of Hooghly has been “frustrated”[vi]. This assessment has been supported by many, including the past Superintending Engineer of Farakka Dr. P.K. Parua (Pers. Comm.) According to Kolkata Port Trust, the dredging of silt at Kolkata Port has been rising from 6.40 million cubic meters (MCM) annually from Pre-Farakka days to four time increase at 21.88 MCM annually during 1999-2003.

The answer, according to Dr. Rudra, lies in the fact that freshwater flow brought by the Hooghly Estuary, even with 40,000 cusecs from Farakka is just too meagre to flush sediments deep down the estuary. The difference between volumes of freshwater brought by Hooghly, as against the tide bringing saline water from south to north is as much as 1:78, making any deep flushing due to freshwater nearly impossible. Dams in the Hooghly Bhagirathi Basin by Damodar Valley Corporation have further arrested freshwater which could have naturally replenished Hooghly estuary. At the same time the stated aims of Damodar Valley Corporation, fashioned on the lines of Tennessee Valley Authority have not been fulfilled.

Currently, the functioning of Kolkata Port and Haldia port is entirely at the mercy of Dredging Corporation of India (DCI) to desilt the river to maintain sufficient draft (allowable depth of a ship’s keel under water). DCI gets about Rs 300-350 Crores per year for dredging the channel, although several problems have been unearthed like dumping the excavated silt back in the estuary from where it is washed back in the channel. In 2009, the Government of India had actually written to the Kolkata Port Trust, saying that it has become a “liability” and it should explain why it should continue to receive dredging subsidies. A PIL has been filed[vii] in 2013 in Kolkata High Court to save Kolkata and Haldia ports by intensive dredging.

It is clear that 40,000 cusecs water from Farakka is not able to help the Kolkata Port much as was envisaged earlier. SANDRP tried to talk with officials at the Kolkata Port Trust, but they declined answering any questions saying that Farakka is a bilateral issue.

This has led to a situation where we have the barrage and the impacts of two countries and millions of people, without even achieving objective for which the project was developed.

2. Sedimentation in the upstream of Farakka Barrage and its massive implications for India and Bangladesh

It is estimated that Ganga carries a silt load of 736 Million Tonnes (MT) annually, out of which about 328 MT of sediment gets deposited in the upstream of Farakka Barrage ANNUALLY[viii]. This annual addition of enormous sediment in the upstream of the barrage has made the river extremely shallow and any ship transport past Farakka has become nearly impossible. As we saw during our visit, islands/chars have formed barely a kilometer upstream the barrage, where animals graze, making any transport nearly impossible.

This massive retention of sediments has resulted in a two-pronged problem:

3. Contribution to delta subsidence and rising sea level in Bangladesh and India

Water released below Farakka barrage has significantly less silt load as about 328 MT silt gets deposited at Farakka. This water has a higher eroding capacity and erodes downstream riverbed. But there is an additional problem: World Heritage site of Sunderbans at the mouth of the Ganga-Brahmaputra-Meghna delta, shared between India and Bangladesh is witnessing possibly the first and highest numbers of Climate Change refugees in the world due to Ingressing Sea which is eating away at smaller islands and the delta. Part reason for this delta subsidence is sea level rise due to global warming and related changes, but the driving reason for encroaching seas is not only sea level rise, but the sinking river delta due to trapping sediment in the upstream dams and barrages like Farakka. The role of river sediments in building deltas is crucial. Ganga-Brahmaputra-Meghana Delta is subsiding rapidly and is categorized as a ‘Delta in Peril’ by experts like Syvitski et al, due to reduction in sediments reaching the delta and compaction of delta, furthering sea level rise. According to recent studies, the rate of relative sea level rise per year in the Ganga Brahmaputra delta is in the range of 8-18 mm per year, one the highest in the world. The related sediment reduction has been a whopping 30% in the twentieth century. (SANDRPs report on Delta Subsidence and Effective Sea Level Rise due to sediment trapping by dams: https://sandrp.wordpress.com/2014/05/07/sinking-and-shrinking-deltas-major-role-of-dams-in-abetting-delta-subsidence-and-effective-sea-level-rise/)

Farakka Barrage has been highlighted as one of the causes for this blocking of sediments at an important juncture. Any role played by Farakka in delta subsidence of GBM Delta has a massive impact on millions of people residing in this delta. According to Prof. Md. Khallequzamman (Pers Comm.), the amount of sediment influx flowing into Bangladesh from upper reaches in India has dropped from 2 billion tons per year in the 1960s to less than 1 billion tons per year in recent years, which is not enough to keep pace with rising sea.[ix]

4. Erosion in the Upstream of the barrage due to Sedimentation

Farakka Barrage is getting silted up due to millions of tonnes of sediment being deposited in the upstream annually. Ganga has been a meandering river, changing courses over centuries, forming paleo channel and ox bows. This deposition of sediment in the upstream is accelerating swinging of Ganga alarmingly to the left bank of the river. This is leading to tremendous erosion in Malda and surrounding regions. More than 4000 hectares of land in Malda has been eroded by the Ganga since 1970s. The river has also breached 8 embankments. Although a number of authors have conclusively written about this and even Legislative Assembly of West Bengal has been unequivocal in saying that “It is accepted all levels that the construction of Farakka Barrage is solely responsible behind the erosion of river Ganges in Malda district”, Central Water Commission trivializes this fact and does not accept any responsibility of Farakka.The only issue CWC seems to be bothered about is the health of the barrage itself which is compromised by erosion on the left bank. In official correspondences of CWC and MoWR scrutinized by SANDRP, the agencies do not mention anything about plight of thousands of people, who are refugees of a swinging river, but are only concerned about the strength of the barrage.[x]

According to Audit Report on Farakka Barrage by Indian Audit and Accounts Departments, between 2006-2012, the “Unintended Consequences” of Farakka include:

- Induced water through feeder canal raised water level of Bhagirathi by about 5 meters near Jangipur and does not allow Bansloi and Pagla to join Bhagirtahi freely. A new wetland due to congestion formed Ahiron Beel which has submerged fertile land.

- The barrage has trapped substantial sediment and hence river in changing course. In homogenous situation the oscillation of river is secular but it gets aggravated due to Farakka Barrage. On account of Rajmahal hills on right bank and Farakka barrage on the channel, the river erodes the left bank.

- The 10 day cycle of increased and decreased release of water from the Barrage has resulted in a complex phenomenon of recharging ground water by river and then receiving base flow from groundwater ( when river is low). The frequent change in water level on account of 10 day altered flow adversely affects the rivers hydro geomorphology leading to escalating bank erosion.

- River bed height in Farakka pondage has increased and the river is compensating this reduction by expanding its cross section sideways

5. Erosion Downstream of the barrage, leading to loss of life and property:

Sedimentation upstream the barrage, coupled with natural swing of Ganga has meant that the river is swinging to the left, encroaching the left bank, leading to erosion in thousands of villages, roads, fields in the downstream of the Barrage in India as well as Bangladesh, causing annual floods. The Irrigation Department West Bengal (Report of the Irrigation Dept for 1997-2001) itself has agreed not only about this erosion due to Farakka Barrage, but has also cautioned about the possibility of outflanking of the Farakka Barrage itself. Many experts maintain the eminent possibility of Ganga outflanking the barrage to flow through its old course of the 15th century, which will reduce the barrage to just a bridge.

On our visit to Farakka, Kedarnath Mandal, a veteran activist working on issued of Ganga and Farakka accompanied us to see extensive erosion in the left bank of the river in the upstream at Simultola as well as downstream in Chauk Bahadurpur. In both these regions, the eroding river has paid little heed to the erosion control measures on the banks. Huge boulders have been swept with the current, destabilizing land in their wake.

We saw extensive bank erosion in the left bank on the downstream where all measures like bull headed spurs, dip trees, porcupines, gunny bags, geo-synthetic covers, boulders bars, boulder crates with nets, etc. have been eroded.

In all this din, the people residing in the chars, their leaders like Kedarnath Mandal, River experts and even the Legislative Council of West Bengal maintain that though erosion and changing courses is a character of Ganga, it has worsened and accelerated hugely since Farakka Barrage. In fact the 13th Legislative Assembly Committee (2004) in its 7th Report notes “It is accepted at all levels that the construction of Farakka Barrage is solely responsible behind the erosion of river Ganges in Malda district”.

6. Near Impossibility of desilting Farakka Barrage

To say that the challenge of desilting Farakka Barrage is Herculean, will be an understatement. The irreversible circle of events is highlighted by the fact that in order to have any appreciable impact, the amount of sediment lifted from the barrage should be at least twice the amount deposited per year, if the project is to be completed even in thirty years. But that seems impossible. According to Dr. Rudra, “Doing so will require a fourteen lane dedicated highway from Malda to Gangasagar” and the transport cost alone “would be nearly twice the revenue earned by Government of India in a year.” Dr. P.K. Parua also accepts that desilting the barrage will be next to impossible.

Such is the scale of sedimentation at Farakka.

7. Source of conflict with Bangladesh

Experts and authorities from Bangladesh have been raising the issue of impact of Farakka for several years now. Farakka Barrage not only obstructs the flow of sediments in Bangladesh, but also diverts waters of Ganga away from Bangladesh delta, depriving millions of fisherfolk and farmers from their livelihood. Water sharing from Farakka, particularly in lean season is now governed by Ganges Water Treaty of 1996. The Treaty holds force between 1 January to 31st May each year and water sharing calculations are based on 10 day flows. Some experts from Bangladesh have maintained that Ganges Water Treaty is not being implemented properly and Bangladesh is receiving less water than its due.[xi] There are issues raised by the Indian side as well of dwindling water availability. All in all, the barrage and the resultant Treaty continues to be a source of impacts for the river and people of the two nations.

- Meeting officials at Farakka Barrage

SANDRP met with the Authorities at the Farakka Barrage Project office, which is under the Ministry of Water Resources (MoWR), at New Farakka. After meeting the officials, it was clear that they have no program for silt management at all. They do not even see this as an area of concern and are only concerned with anti-erosion works, which are failing miserably, and releasing water to Kolkata Port, which is not improving its navigability.

While some may argue, rather irrelevantly (considering the warnings of Kapil Bhattacharyya), that Engineers in 1950s, 60s and 70s were not equipped or aware of the issues related to sediment and its far-reaching impacts like erosion, deposition, floods, even sea level rise, the same in any case cannot be said about the current water management. They have the privilege of better knowledge, better resources and also lessons from past experiences. But despite having clear evidence that silt of Ganga is playing havoc with millions in India as well as Bangladesh, the Farakka Barrage Authorities tell us that they have no plan for silt management the barrage except annual erosion control measures.

The mandate of the barrage authorities is also 120 kms of bank erosion works, 40kms in the upstream and 80kms in the downstream. We were told on the condition of anonymity that this extensive work leaves little time even for maintaining the barrage. The bank protection work is also not permanent and is eroded with flood waves. The bureaucratic set up at Farakka makes it impossible to take proactive decisions about Barrage maintenance. The gates of the barrage need replacement, but there is hardly any agency interested in working for Farakka Barrage due to bureaucratic delays.

The officials told SANDRP that the only desilting measure that can be adopted is opening all gates of the Barrage, but that will not be possible unless all gates are replaced as many gates are faulty. Replacing all gates of Farakka will take at least two more years and we do not know even after that whether silt can be flushed. Such a flushing will need a major flood event and the impact of such sudden flushing of billions of tonnes of silt in the downstream will be unprecedented & huge.

Meeting with Farakka Barrage Authorities leaves one with more questions than answers.

- Interview with past official of Farakka

SANDRP discussed the multiple issues of Farakka with one of the senior retired official from the Farakka Barrage Authority who has seen the work of the FBPA closely over several years. Some excerpts from these discussions.

SANDRP: Sir, do you think Farakka is fulfilling its functions?

Answer: Farakka was not only designed for diverting water for Hooghly, it was foreseen that there may be an Irrigation component and even a hydropower component. But the inflow at the barrage was over calculated. We never had that sort of inflow in the project. Add to this Treaty with Bangladesh in 1996 and India was left with little water. I would say objectives of Farakka were only partially fulfilled. The barrage has a designed discharge of 27,00,000 cusecs and we have been able to achieve that discharge only twice since commissioning the barrage. In the recent years, water flow has been declining sharply at the barrage. This further handicaps all its functions.

SANDRP: There are several problems associated with silt deposited in the upstream of the barrage like floods, change in course of the river, erosion, etc. Is there any way to tackle this deposited silt?

Answer: Yes, that is a serious problem. This is being faced by ports and barrages the world over and also across India. There are so many players responsible for the increasing silt load and reduced water in the river, right from Nepal.

We can say that the scale of the sediment issue was not understood when the barrage was designed, the engineers then did not have the knowledge or tools for this. Even now, there is no easy way this issue can be tackled. Desilting the barrage would be very costly, and what would be do with the collected silt? Malda and Murshidabad region is densely populated, we cannot dump it anywhere. If we dump it in the river, there will be other problems. It is possibly an evil we have to live with now.

SANDRP: There are plans to erect about 16 more such barrages on the Ganga main stem. What would be the lessons from Farakka for these barrages?

Answer: I think this is a horrible plan. In addition to the challenge of silt, I wonder where will the water come from? Supplies from Upper Ganga Canals are increasing, reducing water flow in the river. Uttar Pradesh is increasing the capacity of Lower Ganga Canals. More and more abstraction will happen. Such a plan does not seem feasible and will be harmful for the river as well.

- Ecological Impacts

- There’s no Hilsa here

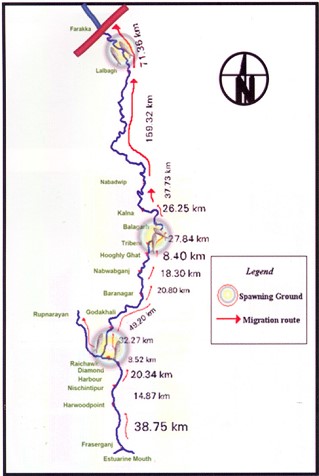

Farakka Barrage has stopped migration of economically important species like the Hilsa (Tenualosa ilsha) and Macrobrachium prawns, both Ilish (Hilsa) and Chingri (Macrobrachium) hold a special significance to people in West Bengal and Bangladesh. A lot has been written about the Barrage’s disastrous impact on Hilsa production and impoverishment of fisherfolk in India and Bangladesh[xii]. About 2 lakh fisherfolk in Malda district alone depend on riverine fisheries and Hilsa here was the backbone of the fishing economy.

Although Central Inland Fisheries Research Institute (CIFRI) has a lab to work on Hilsa, the institute is not working on Fish passes or Hilsa Hatcheries at the Barrage itself!

Prior to com missioning Farakka Barrage in 1975, there are records of the Hilsa migrating from Bay of Bengal right upto Agra, Kanpur and even Delhi covering a distance of more than 1600 kms. Maximum abundance was observed at Buxar (Bihar), at a distance of about 650 kms from river mouth. Post Farraka, Hilsa is unheard of in Yamuna in Delhi and its yield has dropped to zero in Allahabad, from 91 kg/km in 1960s. Studies as old as those conducted in mid-seventies single out Farakka’s disastrous impacts on Hilsa, illustrating a near 100% decline of Hilsa above the barrage post construction.[xiii]

missioning Farakka Barrage in 1975, there are records of the Hilsa migrating from Bay of Bengal right upto Agra, Kanpur and even Delhi covering a distance of more than 1600 kms. Maximum abundance was observed at Buxar (Bihar), at a distance of about 650 kms from river mouth. Post Farraka, Hilsa is unheard of in Yamuna in Delhi and its yield has dropped to zero in Allahabad, from 91 kg/km in 1960s. Studies as old as those conducted in mid-seventies single out Farakka’s disastrous impacts on Hilsa, illustrating a near 100% decline of Hilsa above the barrage post construction.[xiii]

We met fishermen who have not caught a single Hilsa in the upstream of the barrage despite fishing for three days. In the downstream too, size and recruitment (population) of Hilsa is affected due to arrested migration at Farakka. Some 2 million fisherfolk in Bangladesh depend on Hilsa fishing. Hilsa in Padma river (Ganga in India) downstream Farakka has also declined sharply due to decreasing water and blockage of migration routes.[xiv]

These fisherfolk have never been compensated for the losses they suffered. They were not even counted as affected people when the barrage was designed and they are not counted even now.

- Fable of Farakka Fish Lock

The tale of Farakka Barrage Fish Lock is another tragic story. Fish Lock is a gated structure in a Barrage that needs to be operated specifically to facilitate migration of fish from the downstream to the upstream or vice versa to breed, feed or complete their lifecycles.

According to Central Inland Fisheries Research Institute (CIFRI), Farakka Barrage has two Fish Locks between gates 24 and 25. The locks need to be operated to aid fish migration and transport fish. We talked with the Engineers at Farakka Barrage Authority, local villagers, fishermen and even the Barrage Control Room officials who operate the gates of the barrage about the functioning of the Fish Lock. No one had heard about a Fish Lock. There is some information that there is one more lock further upstream in the river, but the FBP Authorities did not seem aware of this.

The control room officials kept showing us the ship lock at the Barrage (which is also rarely used due to turbulence and sedimentation) and told us categorically that “There is nothing called as fish lock here”. The locks have not been operated for a minimum of a decade, possibly much longer.

Who is responsible for the loss of fisherfolk income in the meantime? Will the Farakka Barrage Authority or the MoWR or the CWC or the Kolkata Port Trust or Inland Waterways Authority of India compensate them?

According to Dr. Parua, fish locks were operated for some time when he was posted at Farakka, but they never worked as planned. He believes that a bare 60 feet fish lock for a barrage that is more than 2.6 kms long is of little use. There should have been more fish locks planned. He also lamented about the non-functionality of Hilsa Fish Hatchery set up at the banks of the barrage. (We were not even told about the presence of this structure by any of the officials or other concerned persons we met and possibly it has now fallen to complete disrepair now.) He said despite Central Inland Fisheries Research Institute (CIFRI) is based in West Bengal and has a special cell to study Hilsa, they or the Fisheries Department have taken no interest in the functioning of the hatchery or the Fish Locks.

2. Vikramshila Dolhin Sanctuary, Bhagalpur

Bhagalpur is barely 150 kms upriver from Farakka and Dr. Sunil Chaudhary, a past Member of the Sate Wildlife Board of Bihar has been working relentlessly on conservation of Gangetic Dolphins, as well as rights of traditional fisherfolk in Bihar and around Vikramshila region.[xv] SANDRP discussed the issue of Farakka and additional barrages with him. Dr. Chaudhary states that not only barrages, but the dredging itself will have serious impacts on Dolphins. Impacts of Farakka Barrage on fish and fisherfolk in Bihar is still being felt. No Hilsa reach here from Farakka and a generation of fisherfolk has suffered due to this. Forget more barrages on the Ganga, we need a review of Farakka Barrage itself as Ganga Mukti Andolan has been asking for years now.

Any work affecting Vikramshila Dolphin Sanctuary will require clearance from State Wildlife Board, State Wildlife Warden and National Board for Wildlife. We hope that such permissions are not given without due diligence and independent application of mind and at least whatever remains of Ganga is maintained.

In conclusion

The issues arising out of Farakka are extremely serious. Our planners and decision makers may claim that many of the impacts were not foreseen (Not entirely true). But the issue cannot be ignored any longer. We need a credible independent review of the development effectiveness of Farakka Barrage, including costs, benefits and impacts.

What we seem to be doing now is to repeat the mistakes of the past with new barrages planned on the Ganga.

The existing Upper Ganga Barrage (Bhimgouda Barrage) has dried up the river in the downstream. The river is diverted in a canal, where people take ritual baths, while the original riverbed is used as a parking lot.

The Lower Ganga (Narora Barrage) has severely affected fish migration & dried up the river in the downstream at least in lean season. The Barrage has a fish ladder, but there is no monitoring or concern as to whether it is working or not. In its report to the World Bank, Uttar Pradesh Government has said that the “condition of the barrage is poor” and has lamented about increased siltation in the upstream of the barrage and the inability to flush the sediments due to poor condition of its gates.[xvi].

Beyond doubt, the existing barrages, especially the Farakka Barrage have had massive impacts on the river, its ecosystems and its people. We have many critical lessons to learn from these experiences. In stead, we are pushing for more barrages on a river which will only compound existing problems.

Ganga is much more than a waterway or a powerhouse. It is a river, supporting not only urban areas and industries, but rural communities, the basin, the ecosystem and myriad organisms in its wake and it needs to be respected as an ecosystem first, rather than for sentimental reasons like mother or goddess.

The Ganga is being fettered at its origin in the Uttarakhand by over 300 hydropower dams. In addition, if it is again dammed many times over times in its main channel, then the government will not have to worry about River Rejuvenation Plan. There will be no river left for rejuvenation.

-Parineeta Dandekar, SANDRP (parineeta.dandekar@gmail.com)

Bibliography:

Dr. Sutapa Mukhopadhyay et al, Bank Erosion of River Ganga, Eastern India –A Threat to Environmental Systems Management

G Verghese, Waters of Hope: Facing New Challenges in Himalaya-Ganga Corporation, India Research Press, 2007

Milliman et al, Environmental and economic implications of rising sea level and subsiding deltas: the Nile and Bengal examples, JSTOR, 1989

Syvitski et al Sinking deltas due to human activities Nature Geoscience, September 2009

Thakkar, Dandekar, Shrinking and Sinking Deltas, Major role of dams in delta subsidence and Effective Sea Level Rise, SANDRP, 2014

A Photo Feature on Farakka Barrage: https://sandrp.wordpress.com/2014/09/29/world-rivers-day-and-ganga-a-look-at-farakka-barrage-and-other-such-calamities/

End Notes:

[1] Pers. Comm.

[i] For a earlier SANDRP report on Farakka, see: https://sandrp.in/dams/impct_frka_wcd.pdf

[ii] http://iwai.nic.in/index1.php?lang=1&level=0&linkid=115&lid=781

[iii] http://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/varanasi/No-environmental-clearance-for-Haldia-Allahabad-Waterway/articleshow/39827972.cms

[iv] https://sandrp.wordpress.com/2014/07/08/will-this-ganga-manthan-help-the-river/

[v] http://www.toxicswatch.org/2014/08/work-commencing-on-ganga-waterway.html

[vi] Dr. Rudra, Kalyan, The Encroaching Ganga and Social Conflicts: The Case of West Bengal, India, 2008

[vii] http://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/kolkata/PIL-to-save-Kolkata-and-Haldia-ports-filed/articleshow/20526985.cms

[viii] Dr. Rudra, Kalyan, The Encroaching Ganga and Social Conflicts: The Case of West Bengal, India, 2008

[ix] For more details see: https://sandrp.in/Shrinking_and_sinking_delta_major_role_of_Dams_May_2014.pdf

[x] http://www.environmentportal.in/files/Farakka%20Barrage.pdf

[xi] Khalequzzaman, Md., and Islam. Z., 2012, ‘Success and Failure of the Ganges Water-sharing Treaty’ on WRE Forum http://wreforum.org/khaleq/blog/5689

[xii] https://sandrp.wordpress.com/2014/09/01/collapsing-hilsa-can-the-dams-compensate-for-the-loss/

http://wwf.panda.org/wwf_news/?186621/Climate-change-could-drown-out-Sundarbans-tigers—study

http://www.the-south-asian.com/april-june2009/Climate-refugees-of-Sunderbans.htm

http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/092181819190118G

[xiii] Ghosh, 1976 quoted in Review of the biology and fisheries of Hilsa, Upper Bengal Estuary, FAO, 1985

[xiv] http://www.downtoearth.org.in/node/2071

[xv] https://sandrp.in/rivers/Dolphins_of_the_Ganga-few_fading_fewer_frolicking.pdf

[xvi] World Bank, Uttar Pradesh Water Restructuring Project Phase II, 2013

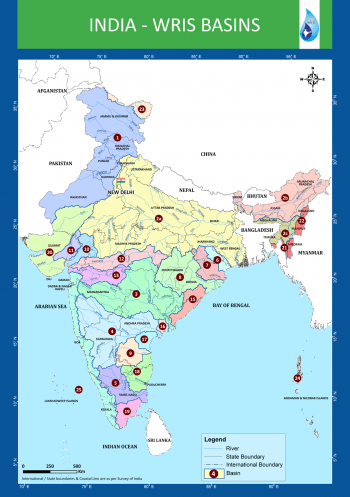

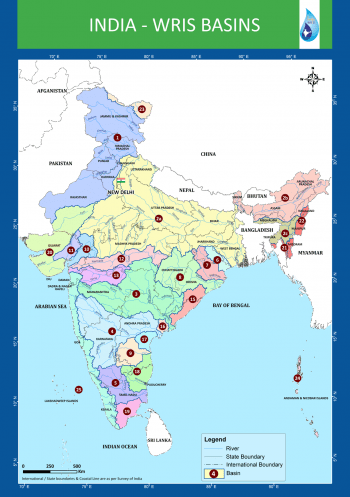

WRIS River Basin Reports: Hits and Misses

Reliable data and information that is both correct and validated on ground, is a pre requisite to understand any feature or activity. And for a river, a constantly evolving and truly complex entity, it becomes even more crucial. The wellness quotient of rivers, their present health status, all these and more can only be understood, once we have the rudimentary knowledge of the river and the basins that they form.

A step in this direction has been taken up by the India WRIS (Water Resources Information System) project (A joint venture between Central Water Commission and Indian Space Research Organisation), that aims “to provide a ‘Single Window Solution’ for water resources data & information in a standardized national GIS framework”[i]. This project has generated 20 basin level reports that share important information on the salient features of the basin, their division into sub basins, the river systems that flow through it and the water resource structures, such as irrigation & hydro electric projects in the basin. Another crucial inclusion is the length of major rivers in each basin, which have been GIS calculated (Geographic information system)[ii] and in a few reports the place of origin of the rivers too is mentioned. (Ganga Basin Report). This is an improvement over the earlier documented river lengths that included the canal length along with the river lengths, in earlier CWC documents (e.g. water and related statistics)!

The Basin reports include basin level maps which also show the proposed inter basin transfer links and the major water resource structures & projects. Individual maps at the sub basin level mark the rivers & their watersheds. The report gives details on the topography, climate, the land use / land cover area , and also the information on hydro meteorological stations like groundwater observation cells, flood forecasting sites and even water tourism sites.

These reports can be downloaded from the WRIS site.[iii]

The reports are an attempt to document the water resources data & information for a better and more integrated planning, at the basin level. A table below tabulates some important parameters from the 20 basin reports.

Missing Dams! It can be seen from table on next page that total number of dams in all the 20 basins come to 4572. Assuming that this includes all the completed large dams in India by Dec 2013 (WRIS report is dated March 2014), if we look at the number of large dams in India as in Dec 2013 in the National Register of Large Dams (NRLD), the figure is 4845. This leaves a difference of 273 large dams, which are missing from the WRIS list! This seems like a big descripancy. Unfortunately, since NRLD gives only statewise list and does not provide river basin wise list and since WRIS list provides only river basin wise list and does not provide the names of districts and states, it is not possible to check which are the missing dams, but WRIS need to answer that.

Sub Basins These 20 basins have been further delineated into a number of sub basins. The sub basins details include the geographical extent of the sub basin, the rivers flowing in it, the states that they travel through, number and size range of watersheds and also the details of dams, weirs, barrages, anicuts, lifts & power houses, accompanied by maps at this level. The irrigation and hydro electric projects in the area are detailed and mapped for greater convenience. The sub basin list is given here to get a detailed picure.

Indus Basin Sub-basins:

- Beas Sub Basin

- Chenab Sub Basin

- Ghaghar and others Sub Basin

- Gilgit Sub Basin

- Jhelum Sub Basin

- Lower Indus Sub Basin

- Ravi Sub Basin

- Shyok Sub Basin

- Satluj Lower Sub Basin

- Satluj Upper Sub Basin

- Upper Indus Sub Basin

| S. No | River Basin | Major river | No. of sub basins | No. of watersheds | No. of water resource structures | No. of water resource projects | |||||||||

| Irrigation | Hydro Electric | ||||||||||||||

| Dams | Barrages | Weirs | Anicuts | Lifts | Power Houses | Major | Medium | ERM* | |||||||

| 1 | Indus (Upto border) | Indus (India) | 11 | 497 | 39 | 13 | 18 | 0 | 45 | 59 | 30 | 40 | 21 | 55 | |

| 2a | Ganga | Ganga | 19 | 980 | 784 | 66 | 92 | 1 | 45 | 56 | 144 | 334 | 63 | 39 | |

| b | Brahmaputra | Brahmaputra (India) | 2 | 180 | 16 | 17 | 5 | 0 | 4 | 21 | 9 | 13 | 3 | 17 | |

| c | Barak & others basin | Barak | 3 | 77 | 4 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 6 | 3 | 3 | |

| 3 | Godavari | Godavari | 8 | 466 | 921 | 28 | 18 | 1 | 62 | 16 | 70 | 216 | 6 | 14 | |

| 4 | Krishna | Krishna | 7 | 391 | 660 | 12 | 58 | 6 | 119 | 35 | 76 | 135 | 10 | 30 | |

| 5 | Cauvery | Cauvery | 3 | 132 | 96 | 10 | 16 | 9 | 24 | 16 | 42 | 3 | 15 | ||

| 6 | Subernarekha | Subernarekha & Burhabalang | 1 | 45 | 38 | 4 | 12 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 5 | 34 | 0 | 1 | |

| 7 | Brahmani & Baitarni | Brahmani & Baitarni | 2 | 79 | 61 | 5 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 8 | 35 | 4 | 1 | |

| 8 | Mahanadi | Mahanadi | 3 | 227 | 253 | 14 | 13 | 0 | 1 | 6 | 24 | 50 | 16 | 5 | |

| 9 | Pennar | Pennar | 2 | 90 | 58 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 7 | 14 | 0 | 1 | |

| 10 | Mahi | Mahi | 2 | 63 | 134 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 10 | 29 | 3 | 2 | |

| 11 | Sabarmati | Sabarmati | 2 | 51 | 50 | 2 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 9 | 11 | 4 | – | |

| 12 | Narmada | Narmada | 3 | 150 | 277 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 4 | 9 | 21 | 23 | 1 | 6 | |

| 13 | Tapi | Tapi | 3 | 100 | 356 | 8 | 11 | 0 | 13 | 2 | 13 | 68 | 2 | 1 | |

| 14 | WFR Tapi to Tadri | Many independent rivers flowing | 2 | 96 | 219 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 18 | 13 | 15 | 1 | 12 | |

| 15 | WFR Tadri to Kanyakumari | 3 | 92 | 69 | 6 | 6 | 4 | 0 | 29 | 19 | 12 | 7 | 21 | ||

| 16 | EFR Mahanadi_ Pennar | 4 | 132 | 64 | 5 | 12 | 12 | 0 | 0 | 12 | 46 | 10 | 0 | ||

| 17 | EFR Pennar _ Kanyakumari | 4 | 165 | 61 | 2 | 2 | 11 | 0 | 6 | 13 | 33 | 4 | 5 | ||

| 18 | WFR Kutch _ Saurashtra | Luni | 6 | 268 | 408 | 1 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 8 | 100 | 4 | 15 | |

| 19 | Area of inland drainage in Rajasthan | Many independent rivers flowing | – | – | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 48 | 0 | 11 | 1 | 1 | 0 | |

| 20 | Minor rivers draining into Myanmar(Burma) & Bangladesh | Many independent rivers flowing | 4 | 54 | 3 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 3 | – | 3 | 4 | 1 | – | |

| Total | 94 | 4335 | 4572 | 203 | 335 | ||||||||||

* Extension, Renovation and Modernization ** Data has been accumulated from the individual Basin Reports from India WRIS[iv]

Ganga Basin

- Yamuna Lower

- Yamuna Middle

- Yamuna Upper

- Chambal Upper

- Chambal Lower

- Tons

- Kosi

- Sone

- Ramganga

- Gomti

- Ghaghara

- Ghaghara confluence to Gomti confluence

- Gandak & others

- Damodar

- Above Ramganaga Confluence

- Banas

- Bhagirathi & others ( Ganga Lower)

- Upstream of Gomti confluence to Muzaffarnagar

- Kali Sindh and others up to Confluence with Parbati

Brahmaputra Basin It is strange to see that the profile divides this huge basin into just two sub basins, when it could have easily divided into many others like: Lohit, Kameng, Siang, Subansiri, Tawang, Pare, Teesta, Manas, Sankosh, among others.

- Brahmaputra Lower

- Brahmaputra Upper

Barak & Others Basin

- Barak and Others

- Kynchiang & Other south flowing rivers

- Naochchara & Others

Godavri Basin

- Wardha

- Weinganga

- Godavari Lower

- Godavari Middle

- Godavari Upper

- Indravati

- Manjra

- Pranhita and others

Krishna Basin

- Bhima Lower Sub-basin

- Bhima Upper Sub-basin

- Krishna Lower Sub-basin

- Krishna Middle Sub-basin

- Krishna Upper Sub-basin

- Tungabhadra Lower Sub-basin

- Tungabhadra upper Sub-basin

Cauvery Basin

- Cauvery upper

- Cauvery middle

- Cauvery lower

Subernarekha Basin No sub-basins.

Brahmani & Baitarani Basin

- Brahmani

- Baitarani

Mahanadi Basin

- Mahanadi Upper Sub- basin

- Mahanadi Middle Sub- basin

- Mahanadi Lower Sub- basin

Pennar Basin

- Pennar Upper Sub-basin

- Pennar Lower Sub-basin

Mahi Basin

- Mahi Upper Sub-basin

- Mahi Lower Sub-basin

Sabarmati Basin

- Sabarmati Upper Sub- basin

- Sabarmati Lower Sub-basin

Narmada Basin

- Narmada Upper Sub-basin

- Narmada Middle Sub-basin

- Narmada Lower Sub-basin

Tapi Basin

- Upper Tapi Sub- Basin

- Middle Tapi Sub- Basin

- Lower Tapi Sub- Basin

West flowing rivers from Tapi to Tadri Basin

- Bhastol & other Sub- basin

- Vasisthi & other Sub- basin

West flowing rivers from Tadri to Kanyakumari Basin

- Netravati and others Sub- basin

- Varrar and others Sub- basin

- Periyar and others Sub- basin

East flowing rivers between Mahanadi & Pennar Basin

- Vamsadhara & other Sub- basin

- Nagvati & other Sub- basin

- East Flowing River between Godavari and Krishna Sub- basin

- East flowing River between Krishna and Pennar Sub- basin

East flowing rivers between Pennar and Kanyakumari Basin

- Palar and other Sub-basin

- Ponnaiyar and other Sub-basin

- Vaippar and other Sub-basin

- Pamba and other Sub-basin

West Flowing Rivers of Kutch and Saurashtra including Luni Basin

- Luni Upper Sub-basin

- Luni Lower Sub-basin

- Saraswati Sub-basin

- Drainage of Rann Sub-basin

- Bhadar and other West Flowing Rivers

- Shetrunji and other East Flowing Rivers Sub-basin

Area of inland drainage in Rajasthan Due to very flat terrain and non-existence of permanent drainage network, this basin has not been further sub divided.

Minor rivers draining into Myanmar and Bangladesh

- Imphal and Others sub basin

- Karnaphuli and Others sub basin

- Mangpui Lui and Others sub basin

- Muhury and Others sub basin

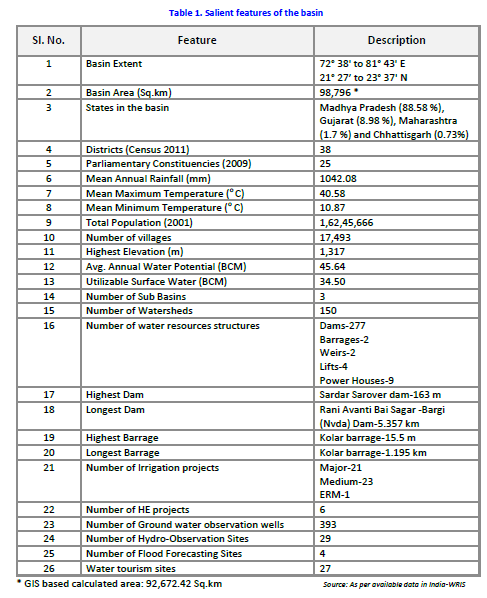

Narmada Basin: Some details To understand the compiled information at the basin level, we take a look at the one of the basin level reports, the Narmada Basin Report[v] (dated March 2014) as an illustrative example. An overview of the basin area right at the beginning, gives its geographical location, shape, size, topography, climate & population. This basic relevant information is tabulated in a concise table for easy access, as given below:

River information The major river flowing in the basin, the Narmada River (also called Rewa) that flows through the 3 states of Madhya Pradesh, Maharashtra & Gujarat, its length (1333 km) and the length of its 19 major tributaries out of a total of 41 is given, based on GIS calculations. There is also a clear river network map of the Narmada basin that demarcates the 3 sub basins along with the watersheds, and shows the dams / weirs /barrages and the rivers in the basin.

- Narmada Upper Sub-Basin, with 16 watersheds

- Narmada Middle Sub-Basin, having 63 watersheds

- Narmada Lower Sub-Basin, with 71 watersheds

The surface water bodies details include the size (less than 25 ha to more than 2500 ha) and type (Tanks, lakes, reservoirs, abandoned quarries or ponds) of existing bodies. Nearly 91.8% of these are tanks.

Irrigation Projects The water resource projects in the basin are as follows:

- 21 Major Irrigation Projects

- 23 Medium Irrigation Projects

- 1 ERM Project

- 6 Hydro-Electric Projects

Interestingly description is only of the major and medium irrigation projects, information on minor projects is completely absent. An attempt to include the details of minor irrigation projects would have made the report more useful. The reports seem to not understand the significance of the smaller projects and their importance for the people and in the conext of the River Basin too.

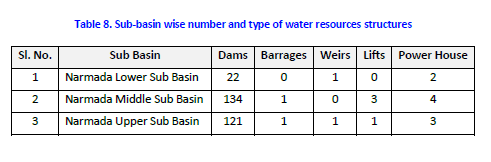

Water resource structures The number and type of big manmade structures in the basin is given. These are a total of 277 dams, 2 barrages, 2 weirs and 4 lifts, of which again the major structures are marked on a map, and details given as in table below. Dams are classified on the basis of storage and purpose they are used for, and the dam numbers are available at sub basin level.

The report gives tabulated data for each of the dams, which is supposed to have name of the river, height, length, purpose, year of commissioning, etc. Since GIS is the strength of ISRO, they could have easily given latitude and longitudes of each dam, but they have not. Shockingly, in case of 186 of the dams, name of the river on which it is built is given as ‘Local Nallah’, and in case of 10 they have left the column blank. This means for nearly 71% (196 out of 277) of the dams they do not even know the name of the river they are build on. This is actually an improvement over the performance of CWC. The CWC’s National Register of Large Dams[vi], we just checked, mentions Narmada only 13 times (for 12 dams of Gujarat and 1 dam of Madhya Pradesh).[vii]

It is well known that Narmada Basin is the theatre of India’s longest and most famous anti dam movement, Narmada Bachao Andolan. The movement involves opposition to Sardar Sarovar, Indira Sagar, Omkareshwar, Maheshwar, Jobat dams, among others. Such social aspects should also form part of any river basin report.

Surface water quality There are 19 surface water quality observation sites in the basin, that collect water data and the report spells out , “As compared to the other rivers, the quality of Narmada water is quite good. Even near the point of origin, the quality of river water was in class ‘C’ in the year 2001 while it was in class ‘B’ in earlier years. As was observed for most other rivers, in case of Narmada also, BOD and Total Coliform are critical parameters.” This shows that even in Narmada Basin, water quality is deteriorating. The statement also remains vague in absence of specifics.

Inter basin transfer links Details of the Par-Tapi-Narmada Link, which is a 401 km long gravity canal and its proposal to transfer 1,350 MCM (Million Cubic metre) of water from ‘surplus rivers’ to ‘water deficit’ areas is given, along with a map. How has the conclusion of surplus or deficit been reached? Does the assessment exhaust all the options including rainwater harvesting, watershed development, groundwater recharge, better cropping patterns and methods, demand side management, optimising use of existing infrastructure, etc? Is this is the least cost option? Does the water balance include groundwater? Who all will be affected by this or even how much land area will be affected by this proposal, there is absolutely no talk of this? No answers in the report.

There’s more to a river There is no information in basin reports on the regulating or statutory bodies that have a say in the basin in the report. However, some information on the existing organisations and inter-state agreements at the various basin level is given at another WRIS location.[viii]

The Basin reports for 20 basins are clearly an asset for understanding and analysing water resource situation. However, there is no mention of the numerous ecological, social and environmental services these rivers provide us with. The demographic details of the basin are available, but there is no information on the flora and fauna, who also need and thrive on the river waters. A good navigation tool for water resource information and river management projects at basin level, nevertheless, for a broader and more comprehensive outlook these reports should have included the following essential aspects too:

- River status: The present water quality & pollution level of the major rivers as well as their tributaries

- River governance: The local committees, civil bodies and institutions that play a role in river basin development

- River safety measures: Effect of the existing and planned river management projects on the state of the river, people and society.

- River ecology: Status of biodiversity, and other ecological aspects of the rivers

Sabita Kausal, SANDRP (sabikaushal06@gmail.com)

END NOTES:

[i] India WRIS: http://india-wris.nrsc.gov.in/wrpinfo/index.php?title=Main_Page

[ii] GIS: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Geographic_information_system

[iii] http://india-wris.nrsc.gov.in/

[iv] Basin Reports available for download: http://india-wris.nrsc.gov.in/

[v] http://india-wris.nrsc.gov.in/Publications/BasinReports/Narmada%20Basin.pdf

[vi] http://www.cwc.nic.in/main/downloads/New%20NRLD.pdf

[vii] For more details, see: https://sandrp.wordpress.com/2013/03/14/how-much-do-we-know-about-our-dams-and-rivers/

[viii] http://india-wris.nrsc.gov.in/wrpinfo/index.php?title=Basins

Who governs our rivers: Too many cooks without care or coordination?

By law, rivers in India belong to the government, however, government has no particular agency that governs our rivers. Our constitution or law does not provide any direct protection to rivers. A large number of entities at centre and state level take decisions that affect our rivers but they do not even seem aware of such impacts. That the decisions and working of a large number of agencies affect the rivers is expected considering the landscape level existence of rivers and society’s wide ranging needs for water and other services provided by the rivers. But the complete neglect of the rivers is certainly not expected. More importantly, people seem to have no role in governance of our rivers! There seems to be neither an understanding nor a recognition that lives and livelihoods of so many people depend on rivers. Nor an understanding as to what is a river and what are its role in the ecosystem, in current and future well being of the society. These blindspots about our understanding of rivers get reflected in our governance of rivers.

India remains an agrarian country, and our water use practices have prioritised use of water for irrigation. Archaic water laws during the British rule looked at water as a resource to be exploited under the jurisdiction of the government. The 1873 Northern India Canal and Drainage Act, stated ‘use and control for public purposes the water of all rivers and streams flowing in natural channels’ as a right of the Government, without any credible and democratic way of deciding what is public purpose.[1] In the same vein the Madhya Pradesh Irrigation Act of 1931 asserted direct state control over water, which find an echo even today in the Bihar Irrigation Act, of 1997 that stresses that all rights in surface water vest with the Government.[2] In fact post colonial water governance did not see any break from the past and essentially the same paradigm prevalant during colonial times continued after independence.

Water in India, as per our constitution is a state (government) subject, and by the same logic water laws in the country too are mostly state based. Thus the state has the constitutional power to make laws, to implement & regulate water supplies, irrigation and canals, drainage and embankments, water storage & hydropower. However, there is nothing in the constitution or law that shows an understanding of what is a river, what services it provides or if there is anything worth conserving in rivers. There is no legal protection for rivers in India.

Moreover as most of the rivers flow through more than one states, the rivers become cause of major interstate disputes when they are seen as sites of big dams. Smaller projects are rarely the reason for intractable interstate disputes. Unfortunately, in post-indepednence India, politicians love big dams and they are seen as most important, if not the only saleable development projects.

The centre can intervene for any interstate differences by constituting a Water Dispute Tribunal for the mediation of the water dispute, but only if invited to do so by the state government. It is within the Central Government powers to regulate and develop inter-State rivers under entry 56 of the constitution, but these powers are rarely used. Entry 56 reads: “Regulation and development of inter-State rivers and river valleys to the extent to which such regulation and development under the control of the Union is declared by Parliament by law to be expedient in the public interest.”

Instead many different regulatory mechanisms have been harnessed and committees formed under various ministries for water management in inter state river basins.

Let’s take a tour of the various agencies involved in governance of rivers in India.

AT THE CENTRE:

Ministry for Water Resources, River Development and Ganga Rejuvenation

It is the apex body[3] at the union level responsible for the country’s water resources and its functions from the river perspective are:

- Rejuvenation of Ganga River and also National Ganga River Basin Authority

- To resolve differences relating to inter-state rivers

- To oversee implementation of inter-state projects occasionally

- To manage, monitor and sanction funds for centrally funded schemes like Accelerated Irrigation Benefits Program, Command Area Development, Rehabilitation of Water Bodies, Bharat Nirman, etc.

- Operation of central network for flood forecasting and warning on inter-state rivers (CWC task)

- Preparation of flood control master plans for the Ganga and the Brahmaputra

- Talks and negotiations on river waters with neighbouring countries

- Operation of the Indus Water Treaty with Pakistan, Ganga Water Treaty with Bangladesh, Mahakali, Kosi, Gandak and other treaties with Nepal, Water Cooperation with Bhutan, Exchange of Data with China under MoU, etc.

There are a plethora of offices/bodies under the water resource ministry, who work under their control. These include the following:

Central Water Commission (CWC) Supposed to be a premier Technical Organization, the CWC[4] is responsible for schemes for control, conservation and utilization of all water resources for various purposes, which includes flood control & irrigation, and overall planning& development of river basins. It also monitors the river water quality at 396 stations located in all the major river basins of India.[5] It is also responsible for co-ordination with states for establishing River Basin Organisations [6], like

- Krishna and Godavari Basin Organization, KGBO [7]

- Brahmputra & Barak Basin Organisation (B&BBO)

- Cauvery & Southern River Organisation (CSRO)

- Indus Basin Organisation (IBO)

- Lower Ganga Basin Organisation (LGBO)

- Mahanadi & Eastern River Organisation (MERO)

- Narmada Basin Organisation (NBO)

- Central Monitoring Organisation (Mon-c)

- Narmada & Tapi Basin Organisation (NTBO)

- Upper Ganga Basin Organisation (UGBO)

- Yamuna Basin Organisation (YBO)

This gives a misleading picture that for practically every river basin there is a basin organisation. In reality, review of CWC annual reports show that there is hardly any activity of these organisations, they in any case do not work to protect the rivers.

CWC is enormously powerful and a big engineering bureaucracy, that hates any sense of participatory governance & accountability. It works more like a big dam lobby, unfortunately. See for example: 1. https://sandrp.wordpress.com/2013/03/14/how-much-do-we-know-about-our-dams-and-rivers/, 2. https://sandrp.wordpress.com/2014/07/12/guesstimating-a-future-questioning-knowledge-formation-expertise-and-development-in-post-independence-india/, 3. https://sandrp.wordpress.com/2014/09/06/why-does-central-water-commission-have-no-flood-forecasting-for-jammu-kashmir-why-this-neglect-by-central-government/, 4. https://sandrp.wordpress.com/2013/06/25/central-water-commissions-flood-forecasting-pathetic-performance-in-uttarkhand-disaster/

Central Ground Water Board (CGWB)

A multidisciplinary scientific organization for the scientific & sustainable development and management of India’s ground water resources. A Central Ground Water Authority has been in 1996 through a Supreme Court order with powers under Environment Protection Act, 1986. On the face of it, CGWB and CGWA may not have any direct role in governance of rivers, the fact is they have a huge role. Firstly, destruction of rivers mean that the groundwater recharge that happens by flowing rivers would stop. CGWB and CGWA should be concerned about this, but have shown no such concern. Secondly, when there is over exploitation of groundwater, it has impact on flow of downstream rivers, particularly in lean season and in low rainfall areas.

A multidisciplinary scientific organization for the scientific & sustainable development and management of India’s ground water resources. A Central Ground Water Authority has been in 1996 through a Supreme Court order with powers under Environment Protection Act, 1986. On the face of it, CGWB and CGWA may not have any direct role in governance of rivers, the fact is they have a huge role. Firstly, destruction of rivers mean that the groundwater recharge that happens by flowing rivers would stop. CGWB and CGWA should be concerned about this, but have shown no such concern. Secondly, when there is over exploitation of groundwater, it has impact on flow of downstream rivers, particularly in lean season and in low rainfall areas.

Central Water and Power Research Station (CWPRS): A principal central agency that provides R&D, and deals with research, services and support pertaining to projects on water resources, energy & water borne transport including those related to rivers.

Central Soil and Materials Research Station (CMRS): It deals with field explorations, laboratory investigations and research in the field of geotechnical engineering and civil engineering materials, particularly for construction of river valley projects and safety evaluation of existing dams.

National Water Development Agency (NWDA)

Set up in 1981-82, the main task of this organisation is to do studies related to inter-linking of rivers. In that sense, it is an anti-river organisation! An autonomous society, some of NWDA’s[8] river related functions include to:

Set up in 1981-82, the main task of this organisation is to do studies related to inter-linking of rivers. In that sense, it is an anti-river organisation! An autonomous society, some of NWDA’s[8] river related functions include to:

- Carry out detailed surveys about the quantum of water that can be transferred to other basins/States

- Prepare feasibility report of the various components of the scheme relating to Peninsular Rivers development and Himalayan Rivers development

- Prepare detailed project report of river link proposals

- Prepare pre-feasibility/feasibility report of the intra-state links

NWDA has not been confident enough to put any of its work in public domain. Some feasibility reports are out following repeated Supreme Court orders in 2002. A perusal of some of these studies shows that it has no concern for the rivers or the services provided by the rivers. It sees all water flowing to the sea as a waste! Which means rivers are a wasteful resource! In its environment impact assessments or in its cost benefit analysis there is no accounting of the services of rivers that would be destroyed if the proposed project go ahead!

National Institute of Hydrology (NIH)

A “premier” Institute in the area of hydrology and water resources, it aids, promotes & coordinates work in the field of hydrology and water resources development.[9] However, it is not known to stand up or speak up for rivers. Its classification of rivers, as mentioned in an earlier blog[10], leaves a lot to be desired. The non participatory tendencies of NIH was apparent in the way it organised a workshop on Environment Flows in Oct 2013[11]. NIH did not find it necessary to invite even the Union Ministry of Environment and Forests for the workshop! NIH also parterned with CIFRI for a flawed assessment of e-flows for Teesta IV project, among other such studies[12].

A “premier” Institute in the area of hydrology and water resources, it aids, promotes & coordinates work in the field of hydrology and water resources development.[9] However, it is not known to stand up or speak up for rivers. Its classification of rivers, as mentioned in an earlier blog[10], leaves a lot to be desired. The non participatory tendencies of NIH was apparent in the way it organised a workshop on Environment Flows in Oct 2013[11]. NIH did not find it necessary to invite even the Union Ministry of Environment and Forests for the workshop! NIH also parterned with CIFRI for a flawed assessment of e-flows for Teesta IV project, among other such studies[12].

Farakka Barrage Authority It is responsible for the operation and maintenance of the Farakka Barrage Project, (FBP), which regulate the flow of water to the Bhagirathi-Hooghly through the feeder canal to maintain navigability of the Kolkata Port.

National Water Academy Earlier known as Central Training Unit, it has been established to impart in house training to water resources personnel from government organisations. Its curriculum includes watershed management, flood forecast &management, environmental management for river valley projects and workshop on River Basin Organisations.