Guest Blog by: Debadityo Sinha (debadityo@gmail.com)

- “We do not want dams; in fact we don’t need it. It is the industries for which they need water, and for which they want us to give up our fertile ancestral land and destroy the forests which we have protected since centuries and put our children in danger.”

An affected villager

Kanhar Dam is one of those projects which is an example of how so called developments worsen the situation for the people and environment. The project conceived 37 years ago has been in abeyance since last 25 years. With the latest inauguration of construction of the dam on 5th December, 2014 after a span of 25 years without a fresh proper cost benefit analysis (CBA), any environment impact assessment (EIA) or Social Impact Assessment (SIA) ever, the commencement of project activities is making way for a large social uprising in the heavily industrialized zone of Uttar Pradesh.

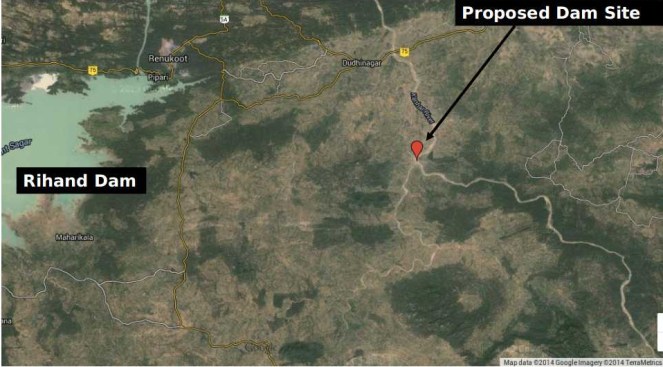

Kanhar Irrigation Project is located downstream of the confluence of River Pagan with Kanhar near village Sugawan in Tehsil Dudhi of District Sonebhadra, Uttar Pradesh. It was originally approved by the Central Water Commission in September, 1976 at an initial budget of Rs. 27.75 Crores. Initially, there was some foundation work undertaken but the project was soon stalled due to inter-state issues, lack of funds and volcanic protests from tribal communities of the region. As per a progress report of the project for 1998-99, the construction work is completely abandoned since 1989-90. Since then, there are numerous occasions when the project was inaugurated, notable among them is one on 15th January, 2011 when the then Chief Minister Mayawati laid foundation stone again. Another inauguration took place when on 12th November, 2012 when Mr. Shiv Pal Singh Yadav (uncle of present CM Akhilesh Yadav), the Irrigation Minister of Uttar Pradesh laid another foundation stone to start the work of spillway. However no work could be taken up.

The project proposes a 3.003 km long earthen dam having a maximum height of 39.90 m from deepest bed level which may be increased to 52.90 m if linked to Rihand reservoir. The project envisages submergence of 4131.5 Ha of land which includes parts of Uttar Pradesh, Chhattisgarh and Jharkhand mostly dominated by tribal communities. The project is expected to provide irrigation to Dudhi and Robertsganj Tehsils via left and right canals emerging from both sides of the dam with capacity of 192 and 479 cusec respectively. The culturable command area of the project is 47,302 ha. The project imposes enormous threat not only on the environment and ecology but also to thousands of tribal families of Vindhyas living there since hundreds of years and has demanded for protection of their forests and proper implementation of R & R (Rehabilitation and Resettlements).

The controversy actually began when the Central Water Commission in its 106th meeting of Advisory Committee for the ‘techno-viability of irrigation, flood control and multipurpose project proposals’ approved the project at an estimated cost of Rs. 652.59 crores at 2008-09 price level. A bare perusal of the minutes shows that there is no consideration of the environment and social impacts of the project. The minutes also show that the approval was granted in the presence of representatives of Ministry of Environment and Forests and Ministry of Tribal Affairs.

Local Voices Suppressed

The inauguration of the project held on 5th December 2014 was marked by the presence of heavy police force and paramilitary forces which were deployed to guard the construction site on the river bed. Few roads have been blocked by Police and it is reported that the entry to the project site is stopped 1.5 km ahead of the construction site. To speed up the work, regular increase of heavy equipments and machinery is in progress. CCTV cameras are also reported to be installed at the site to keep a regular check on the activities.

There is a constant effort by the administrative authorities to suppress the voices of aggrieved and affected raised against the project and those who have attempted to do so are being arrested under the Uttar Pradesh Gunda Niyantran Adhiniyam, 1970 or ‘Gunda Act’. There are repeated incidences of arrests and FIRs against the local people. Incidences of people-police clashes are now becoming a daily routine affairs. Recently the SDM, Dudhi along with the other policemen was also injured in a similar clash. In retaliation to it, there were series of arrests being made by the police and FIRs were filed against 500 unnamed locals. There is an atmosphere of fear already created among the villagers in the region.

The question arises is, whether due procedure has been adopted by the state government as prescribed under law? And if yes then what is the reason for suppressing the voices and why is so such chaos being generated by the government? The project is in controversy due to several questions which are still left unanswered and requires a detailed clarification from the State Government.

The rise of Kanhar Bachao Andolan

The Kanhar Bachao Andolan (KBA) is the first of its kind integrated protest which emerged in the form of an organization in the year 2002 under leadership of a Gandhian activist Bhai Maheshanandji of Gram Sawaraj Samiti based in Dudhi tehsil of Sonebhadra and Gram Pradhans of villages which would be submerged if the project is implemented. The KBA has been raising the issue of tribal rights and discrepancies in the R & R before the state govt. through representations, protests and petitions in High Court. There is a continuous peaceful campaign against the project by KBA since a decade including the unceasing protest which started from 5th December, 2014 on the other side of the River Kanhar opposite to the construction site. Fanishwar Jaiswal, who is a former-Gram Pradhan of Bhisur village and an active member of KBA said, “There was a public meeting organized by the MLA of Dudhi in June, 2014 to address the R & R issues. The Gram Pradhans of several villages presented their views against this project and also submitted written representations; however those views and protests were never registered by the government in any of their reports.”

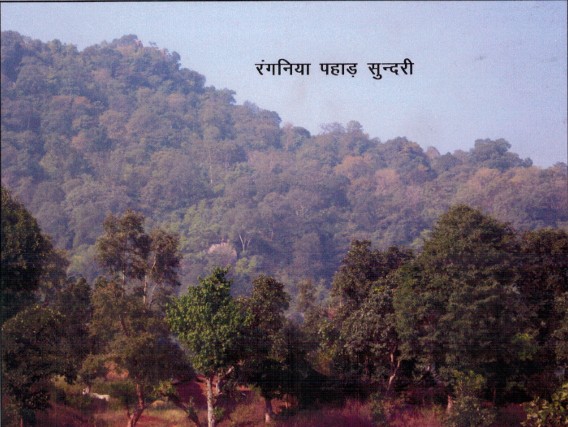

Rich Forests and Tribal Culture at Stake

I got a chance to visit Sonebhadra district in July, 2014 where I came to know about this project and the ongoing protests. I visited the project area and interacted with the people of Sundari and Bhisur villages of Dudhi tehsil which are the affected villages among several others. Dense forests and agricultural fields were the most common landscape feature. One could have seen the abandoned machines, several of which were half-sunk to the soil, broken houses with ghostly appearances which were informed as the once constructed officer’s colonies of the project and old rusted sign boards stating ‘Kanhar Sinchai Pariyojna’. Those structure and abandoned equipments were clear evidences of the Kanhar project which was abandoned long back by the government.

Till 1984, a large number of trees were felled by the government in the midst of protests by the tribal communities. But, since then the work did not take place and there was no displacement of tribals. They have now planted more forests in their villages and have their own regulation bodies for protection of these Forests. “Cutting trees is seen as sin in our culture and we have strict fines and punishments if someone does that. Trees are our life and we are protecting them for our children”, said Pradhan of village Sundari which will be the first village to be submerged by the project.

We discussed about the status of biodiversity and came to know about their dependence on traditional medicines which they obtain directly from the forests. All the villagers I met were satisfied with their rural lifestyle and have developed their own way of sustaining agricultural production by choice of specific vegetable, pulses and crops depending on climate.

It was informed that every year elephants visit the Kanhar River from the Chhattisgarh side. Animals like Sloth Bear, Leopard, Blackbuck, Chinkara and several reptiles are abundantly noticed by people due to presence of hills and forests in the region.

‘We do not want dams; in fact we don’t need it. It is for the industries which need water, and for which they want us to give up our fertile ancestral land and destroy the forests which we have protected since centuries’, said a villager.

It is suspected that the Kanhar dam is being constructed to supplement the Rihand dam to provide water for the industries in Sonebhadra and adjoining region. It seems that the government has not learnt from the experience of Rihand dam which was constructed in 1960s in the same district in the name of irrigation, but gradually diverted the water for thermal power plants and industries. The water in Rihand dam is now severely contaminated with heavy metals which has entered the food chain through agriculture and fish. Like the Rihand dam, the new project will cause more destruction than good to the people of the region.

Vindhya Bachao’s Intervention

It is very clear that the project is going to destroy a huge area of dense forests and going to displace not only the tribal communities from their roots but also affect the rich flora and fauna of the Sonebhadra. To know about the actual status of the environment and forests clearance of the project, RTI (Right to Information) applications were filed with the Ministry of Environment, Forests and Climate Change in July, 2014. The belated reply was received only in Dec, 2014 on initiating a first appeal. The responses states that the ‘Environment Clearance’ was granted on 14.04.1980 which is more than 30 years old and therefore any further information with respect to the same cannot be granted since the same is exempted under the RTI Act 2005. Hence, two things are clear that the project requires a fresh ‘Environment Clearance’ under the EIA Notification, 2006 & a forests clearance prior to start of any construction activity.

In view of this fact, On 22nd December, 2014 an application was filed by Advocate Parul Gupta on behalf of applicants Debadityo Sinha (Vindhya Bachao) and O.D. Singh (People’s Union for Civil Liberties) before the National Green Tribunal praying for taking action against the UP Government for carrying out construction activity of the project without statutory clearances under EIA Notification, 2006 and Forest (Conservation) Act, 1980. The application came up before the bench of Justice Swatanter Kumar on 24th December 2014 wherein stay orders were issued against the Government with clear indication that no construction activity shall be allowed to be undertaken if they do not have ‘Environment’ ‘ and ‘Forest’ Clearance’ as prescribed under law.

The major Environmental and Social issues which require to be carefully considered before the project is allowed to move ahead are as follows:

- Large Social Implications: Nearly 10,000 tribal families are going to be affected directly who will lose their ancestral land permanently. Gram Sabhas of the project affected villages has already passed a consensus against the project and submitted the same to the State Govt.

- Dense Forests will be lost: The Renukoot Forest Division is one of the dense forests of Sonebhadra with tree density of 652 per hectare as per data obtained from a forest clearance application involving the same forest division. The Kanhar project document shows 4439.294 Ha of land categorized as ‘Forest and others’. In such case, lakhs of trees will be affected by this project which would cause significant impact on environment, wildlife and livelihood of tribals.

- Loss of Rich Biodiversity: Vindhyan mountain range is known for the wildlife and rich diversity of medicinal plants which are inherently linked with tribal culture. Scientific Publications shows there are at least 105 species of medicinal plants in the region which are extensively used as traditional treatment by tribal people. The project will endanger the remaining few patches of forests which are not only the last few remaining patches of rich biodiversity but refuge to several wild animals in this heavily disturbed landscape. Conversations with the villagers will reveal presence of mammals like Sloth Bear, Leopard, Blackbuck, Chinkara, Jackal etc and several reptiles including Bengal monitor and snake species in these forests. The submergence area falling in Chhattisgarh is reported to be an elephant corridor.

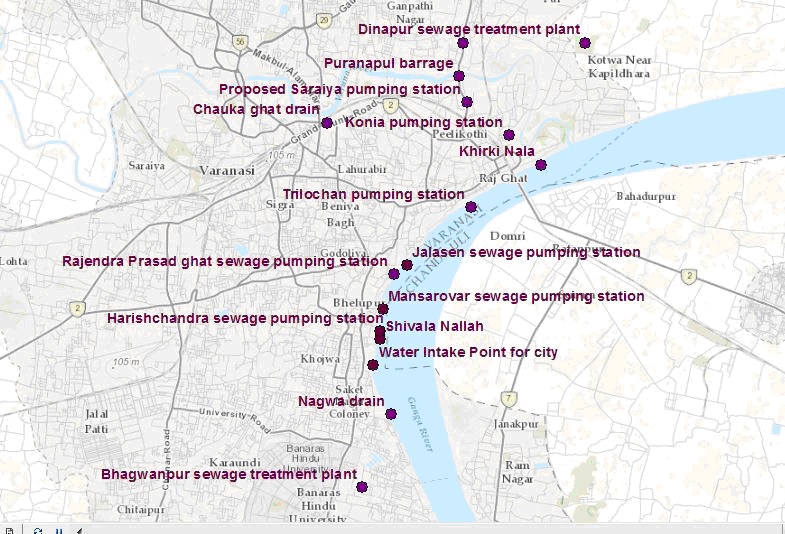

- Immense loss to ecology of river Sone and Ganga: Kanhar is a major tributary of River Sone which forms an important catchment of Ganga River Basin. After construction of Rihand Dam and Bansagar dam and various other water abstraction structures owing to number of industries in the region because of availability of coal mines-River Sone is one of the most exploited system which has lost its riverine characteristics. Central Inland Fisheries Research Institute reported disappearance of 20 fish species from Sone in the time span between 1976 and 2011 which is attributed to increased abstraction of water from the Sone river system. The report clearly states that ‘damming of rivers or tributaries is the root cause of river obstructions causing severe modifications and perturbations to the river flow, velocity, depth, substratum, pools, ecology and fish habitat’. There is reporting of 14 exotic alien species in the river. The report claims that the river Sone is in critically modified (class F) condition with discharge of mere 5.16% of Mean Annual Runoff (MAR) and it will require at least 34.2% of MAR to bring it to slightly modified class (class B). In such a scenario, damming of 5200 km2 of the total catchment of 5,654 km2 of river Kanhar will be disastrous for the river Sone depriving it of the major share of the present water availability. As Sone river system forms an important catchment of River Ganga, the impact on ecology of River Ganga is undeniable.

- Contribution to Climate Change: We will lose lakhs of trees which would act as carbon-absorption system. To double the problem, the carbon which is locked in the forests will be released to atmosphere when these trees will be felled. While Carbon Dioxide is released from aerobic decomposition of plants, the anaerobic decomposition of organic matters will release methane which is 24 times more potential GHG than Carbon Dioxide. There is global evidence which support production of GHGs in dams, the quantity of which varies on several parameters like climatic conditions, water depth, water fluctuation, area of submergence, dissolved oxygen etc. Emission of GHGs like Methane is known for a positive feedback trigger which would lead to more absorption of heat causing further rise in temperature, thus increasing the rate of anaerobic decay in the reservoirs and release of more Methane.

- Lack of Proper Cost-Benefit Analysis: The cost benefit ratio of such projects are calculated on investment and direct benefits from the projects with consideration of impact of project on people & ecosystem, which are often underestimated and excluding socio-cultural costs and cost of a healthy environment and cost of services provided by the river, forest and other ecosystems. The monetary value of the impacts such as on forests, biodiversity, fishing, non-use values, public money spent on infrastructures, cultural loss and other negative impacts are not considered at all.

- Lack of Options assessment There has been no options assessment as to establish that this proposed dam is the best option for water resources development in the Kanhar/ Sone basin.

Conclusion

There is no justification for the project. There has not even been an application of mind if the project is beneficial to the people and society. There is not even any impact assessment, nor any democratic decision making process. A huge amount of public money is already spent on development of schools, roads, hospitals, houses etc in the area, which will be lost permanently by this project. At the time, when this project was incepted in 1976 the environment and social scenario of the country and this region was very different from what it is today. River Sone was not in critically modified state, Forests of Sonebhadra and adjoining regions were still intact, human population was lesser, technology was not so advanced, science of climate change was not fully understood and the need of protection of environment was not felt or required as it is today. In 1976, protection of rivers was not a primary concern as the problems were not evident as it is today. In such scenario furthering such abandoned projects shows poor understanding of environment and insensitive attitude by the policy makers. It is thus important to undertake a proper cost-benefit analysis, a fresh Environment Impact Assessment and Social Impact Assessment, conduct proper options assessment to understand the implications of this project on the ecological balance and people keeping into account the present scenario. Such studies should undergo a detailed scrutiny and public consultation process.

- About the Author: Debadityo Sinha is coordinator of Vindhya Bachao, an environment protection group based in Mirzapur. He can be contacted at debadityo@vindhyabachao.org. More details on the project can be accessed at www.vindhyabachao.org/kanhar.

POST SCRIPT UPDATE on March 16 2015 from the author:

Update from NGT hearing dated 12th March, 2015

The Ministry of Environment, Forests and Climate Change has filed its reply before the National Green Tribunal confirming that there exists a confusion with respect to grant of forest clearance diverting 2500 acres of forest land for construction of the Kanhar dam. The Ministry has defended itself claiming that the Forest Clearance dates back to the time when the Ministry was not in existence and therefore the files pertaining to the same cannot be traced. However, it has shifted the burden of proof on the State of U.P. indicating that a letter dated 28.8.1980 by the then ministry of agriculture implies the grant of fc and must be produced by the state.

The state in defence has filed a bunch of letters which according to them refers to the grant of forest clearance. However, the state has failed to produce thee letter dated 28.8.1980 which is claimed to be the FC granted to the project.

The court observed that :

Learned counsel appearing for MoEF submits that the original letter of 1980 granting Forest Clearance to the Project Proponent is not available in the records of the MoEF. Similar stand is taken by the Project Proponent. However, both of them submit that the preceding and subsequent transactions establish that clearance was granted.

…..

Since it is a matter of fact and has to be determined on the basis of record and evidence produced by the parties, we grant liberty to the Applicant to file Replies to this Affidavit, if any, within three days from today.

We also make it clear that one of the contentions raised before the Tribunal is whether it is an ongoing project for number of years or it’s a project which still has to take off and which law will be subsequently applicable today. Let the Learned counsel appearing for the parties also address to the Tribunal on this issue on the next date of hearing.

Ms. Parul Gupta appeared for the applicants while Mr. Pinaki Mishra and Mr. Vivek Chhib appeared as counsel for State of U.P. and MOEFCC respectively. The matter is now listed for two days- 24th March, 2015 and 25th March, 2015 for arguments. For the order click here , for Press Release click here

POST SCRIPT ON April 14, 2015:

Urgent Alert

Firing in Sonbhadra, UP

Police firing in Kanhar anti dam proterstors early morning today

against illegal land acquisition by UP Govt

Firing done on the day of Ambedkar Jyanti

Police firing on anti land acquisition protesters at Kanhar dam early morning today. One tribal leader Akku kharwar from Sundari village have been hit by bullet in chest, Around 8 people have been grievously injured in the firing and lathi charge by the police. Thousands of men and women are assembled at the site to intensify the protest against on Ambedkar jyanti. The protesters were carrying the photo of Baba Saheb to mark the day as ” Save the Constitution Day”. Akhilesh Govt fired arbitrarily on the protesters among whom women are in the forefront. Most of the women have injured. The firing is being done by the Inspector of Amwar police station Duddhi Tehsil, Sonbhdara, UP.

Condemn this criminal Act and join in the struggle of the people who are fighting against the illegal land acquistion and constructing illegal Dam on kanhar river.

Roma

Dy Gen Sec

All India Union of Forest Working People

POST SCRIPT on April 20, 2015: Update from Roma:

Chhattisgarh Bachao Andolan

A fact finding team of the Chhattisgarh Bachao Andolan consisting of Alok Shukla, Sudha Bharadwaj, Jangsay Poya, Degree Prasad Chouhan and Bijay Gupta visited the dam affected villages of the Kanhar Dam in UP and Chhattisgarh on 19th April 2015.

The team first visited Village Bheesur which is closest to the dam site and interacted with the affected families who are mostly of the Dalit community who were still deeply affected by the repression of the 14th April and 18th April.

The affected men and women were very articulate about their grievances and extremely legitimate demands. They explained that they were first told about the Kanhar Dam in the year 1976 when the then Chief Minister ND Tiwari promised 5 acres of land, one job in each family and a house measuring 40’x60’, apart from full facilities of education, health, electricity and water to the 11 affected villages of Uttar Pradesh namely Sundari, Korchi, Nachantad, Bheesur, Sugwaman, Kasivakhar, Khudri, Bairkhad, Lambi, Kohda and Amwaar. In 1983 it is correct that compensation payments were made at the rate of Rs. 1800 per bigha (approximately Rs. 2700 per acre) to the then heads of households. After this the villagers have got no notice whatsoever.

On 07-11-2012 the Irrigation Minister laid the foundation stone of the dam. It was claimed that now a consolidated sum of Rs7,11,000 would be given to the heads of households as identified in 1983 and houses of 45’x10’ dimensions would be constructed for them. The farmers are rightly arguing that they have been in physical possession of the lands all these years and therefore they should be compensated as per the 2013 Act. The government must be sensitive to the fact that the earlier households have multiplied and the compensation must be provided to all adult families who will lose their livelihood. It is also very pertinent that in the meanwhile the Forest Rights Act, 2006 has come into existence and we found that many of the farmers have been granted Pattas under the Act; however the government is refusing to compensate them for the loss of such lands, which is absolutely against the spirit of the Act.

The work of the dam was started on 04.12.2014 and from 23.12.2014 the villagers were sitting in continuous dharna. On that very day, efforts were made to intimidate them. While the SDM and District Magistrate did not intervene till about 6pm, at about 7pm the Provincial Armed Constabulary (PAC) of which about 150 jawans were deployed at the dam site interfered. After the Tehsildar assaulted a young man Atiq Ahmed, people rushed in from the weekly market and a fracas ensued. Right from that day cases were foisted on 16 named and 500 unnamed persons.

Despite this, the villagers continued with their peaceful protest, however since the government was not carrying on any negotiations and at the same time the dam work was progressing, on 14th April they decided to shift the venue of the dharna closer to the site. The PAC opened fire and a bullet passed through Akklu Chero (Cherwa) – an adivasi of Sundari village. 39 persons were injured, 12 of them seriously. The deployment of the PAC was increased to about 500-1000 jawans.

On 18th April early in the morning the administration was determined to remove the protestors. The district force and PAC surrounded the dharna site, uprooted the pandal and mercilessly beat and chased the villagers right up to their villagers. They entered Village Bheesur and not only beat up men and women, but vandalized a motor and motorcycle of Ram Lochan. Colesia showed us her injured arm and fingers and was in tears because she did not know where her husband Mata Prasad was.

People were not certain where missing family members were since the injured have been taken to the Dudhi Health Centre and if any person tries to contact them they face the threat of arrest since between the cases made out against them for the events of 23rd December, 14th April and 18th April cover about 956 persons. But the team found out that the following had been injured mostly with fractures and were possibly hospitalized. The number of women injured is significant:-

Village Bheesur – Rajkalia, Kismatiya Mata Prasad, Uday Kumar and Phoujdar (all ST)

Village Korchi – Phoolmatiya, Butan.

Village Sundari – Ram Bichar, Shanichar, Zahoor, Azimuddin, Jogi.

Village Pathori Chattan – Bhagmani, Ram Prasad, Dharmjeet.

Similarly the PAC people chased the protestors of Village Sundari too right up to the houses on the outskirts of the village. They damaged motorbikes and cycles even setting fire to them.

We observed that the work at the dam site seemed to be progressing fairly fast. The height of the dam which was earlier stated to be about 39.90 m appears to have been increased subsequently to 52.90 m increasing the apprehensions of the people. The Police had cordoned off the area and there were still a large number of PAC trucks and personnel in their makeshift camp of sheets.

When the team reached Village Sundari, there was an extremely tense atmosphere. Some dominant caste-class persons were holding a meeting in which others seemed to be quite subdued. Some very vocal local leaders told us that they do not want any interference from any outside NGO or organization. Most of them were quoting the DM Sanjay Kumar belligerently saying that he had said that all protest and movements should stop. Otherwise he would foist so many cases that they would rot in jail for the rest of their lives and use up all the compensation in paying lawyers. Some persons who seemed to have been sent by the administration were clicking our photos when we introduced ourselves. The leaders told us that they had decided to accept the compensation and would be going to the DM to inform him so as that was the only way the cases would be lifted. While it was clear that not all the persons in the meeting were in agreement with this “decision”, they were clearly cowed down by the cases and the pressure being brought by the administration.

However our most tragic experience was in the affected villages of Chhattisgarh in block Ramchandrapur of district Balrampur. They fall in the “Sanawal” constituency of erstwhile Home Minister Ram Vichar Netam who had assured the villages that there would be no submergence whatsoever in Chhattisgarh. Even when the current MLA Brihaspati Singh of Congress tried to hold a meeting at Sanawal in which he

invited the protestors of UP, lumpen supporters of Ram Vichar Netam made it difficult for him to educate the villagers about this.

We were shocked to find that the Water Resources Department of Chhattisgarh admits that the following 19 villages are to be submerged – Jhara, Kushpher, Semarva, Dhouli, Pachaval, Libra, Kameshwarnagar, Sanawal, Tendua, Dugru, Kundru, Talkeshwarpur, Chuna Pathar, Indravatipur, Barvahi, Sundarpur, Minuvakhar and Trishuli; and 8 to be partially submerged – Chera, Salvahi, Mahadevpur, Kurludih, Tatiather, Peeparpan, Ananpur, and Silaju. Yet the villages are in blissful ignorance.

Only after the incident on the UP side of the dam occurred, on 18th April an Engineer came to Jhara village and stated that 250 acres of land would be submerged out of which 100 acres was private land. But even this is not the truth since it is clear that the entire village is to be submerged. As we were leaving Jhara village we saw a whole convoy of 6 Government Scorpios rushing through the village. Clearly, the state at some point has to begin some legal acquisition proceedings and seem to be at a loss as to how to do so.

Strangely enough, keeping up the pretence of no submergence Shri Netam has had many constructions sanctioned in Sanawal and surrounding villages whereas ordinarily, once there is an intention to acquire, government expenditure is kept to a minimum.

As we returned to Ambikapur, we heard that another fact finding team from Delhi who were to meet with the injured in hospital and the Collector Sonebhadra, had been detained for questioning.

The rapidity and the ruthlessness with which the dam is being built, at any cost, indicates that is unlikely to be for the stated purpose of irrigation. With large industrial projects coming up in Sonebhadra UP and even in neighbouring Chhattisgarh and Jharkhand, on the cusp of which this dam channelizes the waters of Kanhar and Pang rivers, it appears to be that providing water to these projects and also hydel power are likely to be the real causes.

The Chhattisgarh Bachao Andolan comes to the following tentative conclusions on the basis of its fact finding –

1. The demands of the project affected farmers, particularly dalits and adivasis, are eminently reasonable and the administration should enter into sympathetic discussion with them to redress their very legitimate and legal grievances. Work on the dam should be stopped during such negotiations so as to create an atmosphere of good will.

2. The PAC used excessive and unnecessary force on the protestors on both 14th April and 18th April. The complaints of the protestors should be registered as FIRs and action should be taken against the errant police jawans.

3. Using the threat of false cases against the protestors to arm-twist them to accept unjust compensation and rehabilitation is a form of state terror. The cases must be reviewed particularly the practice of filing cases against “unknown” persons, and malicious cases must be withdrawn.

4. In the State of Chhattisgarh, there has been absolutely no transparency, information or following of legal procedure with regard to affected 27 villages. The provisions of the 2013 Act beginning with the pre-acquisition procedure of Social Impact Assessment, Gram Sabha Consultation (all these areas are Scheduled areas), determination of Forest Rights, Public Hearing on Rehabilitation and Resettlement packages etc must be strictly followed.

5. Finally, the attitude of the Uttar Pradesh Government and the district administration of Sonabhadra in restraining activists from entering the area or making an enquiry into the facts on the ground is undemocratic and reprehensible.

Delhi Contact : c/o NTUI, B – 137, Dayanand Colony, Lajpat Nr. Ph IV, NewDelhi – 110024, Ph -9868217276, 9868857723,011-26214538

To: “cmup@nic.in” <cmup@nic.in>

Cc: Amod Kumar <amodk2013@gmail.com>; Rigzin Samphel <rigzin123@gmail.com>; Sanjay Kumar <sanjaykumarias02@yahoo.co.in>

Sent: Saturday, April 25, 2015 1:34 AM

Subject: Stop construction of Kanhar Dam

Further reading:

कनहर कथा http://tehelkahindi.com/story-of-kanhar-barrage-project/

– छत्तीसगढ़ सीमा पर संगीनों के साए में कनहर बांध का निर्माण

http://naidunia.jagran.com/chhattisgarh/raipur-kanhar-dam-making-start-in-chhattisgarh-border-279906

(Nai Duniya)

– Despite NGT stay, UP govt goes ahead with construction of dam

https://www.hindustantimes.com/india-news/despite-ngt-stay-up-govt-goes-ahead-with-construction-of-dam/article1-1304050.aspx

– “Kanhar dam case: Green panel pulls up environment ministry” By IANS | 22 Feb, 2015

END NOTES:

- For NGT order on Kanhar Dam, see: http://vindhyabachao.org/embeds/kanhar/NGT-order-Kanhar.pdf

- For a brief video clip on project location, see: http://youtu.be/ZZD_Jk2hDs0

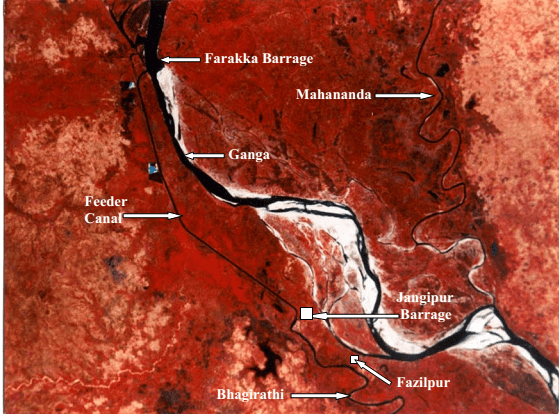

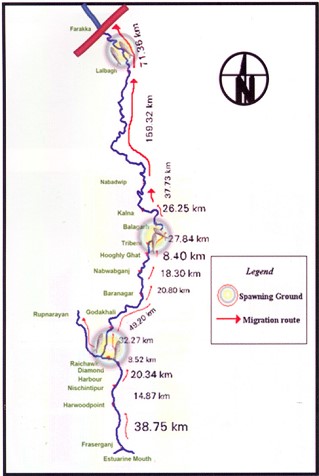

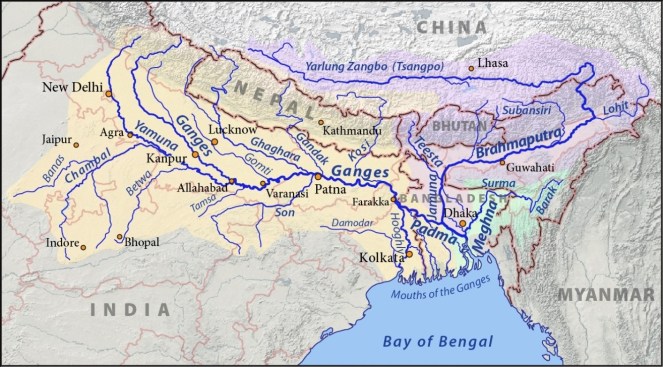

missioning Farakka Barrage in 1975, there are records of the Hilsa migrating from Bay of Bengal right upto Agra, Kanpur and even Delhi covering a distance of more than 1600 kms. Maximum abundance was observed at Buxar (Bihar), at a distance of about 650 kms from river mouth. Post Farraka, Hilsa is unheard of in Yamuna in Delhi and its yield has dropped to zero in Allahabad, from 91 kg/km in 1960s. Studies as old as those conducted in mid-seventies single out Farakka’s disastrous impacts on Hilsa, illustrating a near 100% decline of Hilsa above the barrage post construction.

missioning Farakka Barrage in 1975, there are records of the Hilsa migrating from Bay of Bengal right upto Agra, Kanpur and even Delhi covering a distance of more than 1600 kms. Maximum abundance was observed at Buxar (Bihar), at a distance of about 650 kms from river mouth. Post Farraka, Hilsa is unheard of in Yamuna in Delhi and its yield has dropped to zero in Allahabad, from 91 kg/km in 1960s. Studies as old as those conducted in mid-seventies single out Farakka’s disastrous impacts on Hilsa, illustrating a near 100% decline of Hilsa above the barrage post construction.

Farakka has profoundly changed the character, sediment regime and flow of Ganga. It is affecting lives of lakhs of people in India and Bangladesh through cycles of erosion, sedimentation, floods and affected fishing. Our response to the issue has been dismal. We have not conducted a single review of costs, benefits and impacts of Farakka Project so far. In addition to Farakka , Lower Ganga (Narora), Middle Ganga, Upper Ganga Barrages (Bhimgoda), Kanpur Barrage, Hydropower projects in Uttarakhand and other upstream states have affected the river in most profound ways. If we want to rejuvenate the Ganga, we need to institute a credible independent review the existing Barrages, not plan new ones. May be we can begin with a demand for such a review for Farakka on urgent basis. One World Rivers Day, let us wish for a long and healthy flow for the Ganga River, a symbol of all flowing rivers in India!

Farakka has profoundly changed the character, sediment regime and flow of Ganga. It is affecting lives of lakhs of people in India and Bangladesh through cycles of erosion, sedimentation, floods and affected fishing. Our response to the issue has been dismal. We have not conducted a single review of costs, benefits and impacts of Farakka Project so far. In addition to Farakka , Lower Ganga (Narora), Middle Ganga, Upper Ganga Barrages (Bhimgoda), Kanpur Barrage, Hydropower projects in Uttarakhand and other upstream states have affected the river in most profound ways. If we want to rejuvenate the Ganga, we need to institute a credible independent review the existing Barrages, not plan new ones. May be we can begin with a demand for such a review for Farakka on urgent basis. One World Rivers Day, let us wish for a long and healthy flow for the Ganga River, a symbol of all flowing rivers in India!