Increasing incidences of Glacial Lake Outburst Floods (GLOFs) are being experienced in the Indian Himalayas. One of the most notable examples of GLOF was the Chorabari Lake GLOF that occurred on 16th June 2013 in Kedarnath, Uttarakhand[1] which was triggered by heavy rainfall induced mass movements into the lake. The GLOF devastated villages of Kedarnath, Rambara, and Gaurikund. Around 6,000 people were officially killed, and a significant number of the deaths were linked to the GLOF. Countless bridges and roads were washed away, and about thirty hydropower plants were affected or completely devastated. Several Hydropower projects resulted in exponential losses to life and livelihoods. Whole of Uttarakhand was affected in the disaster, and a significant proportion of it was related with GLOF.

In Feb 2021, following the collapse of a rock glacier in the Rishiganga River in Uttarakhand, a huge flood wave was generated in the river even when the water levels were low. The rapidly advancing wave with debris destroyed 13.5 MW Rishi Ganga HEP and 520 MW Vishnugad Tapovan barrage, leading to the death of over 200 people, most of whom were workers at the dam sites. While there was no GLOF component to the disaster, there was a clear nexus of changing climate and hydropower in high altitudes. Local communities had protested and even filed cases against hydropower projects which collapsed and caused deaths. Till date no independent report is available about what happened in this disaster, who played what role and what lessons we can learn.

Then in October 2023, moraine wall of South Lhonak Glacial Lake in Sikkim collapsed generating a 20m high wave. The breach caused sudden displacement of over 50 MCM (Million Cubic Meters) of water with a peak discharge of 48,000 cumecs (Cubic Meters per second). The incident completely destroyed 1200 MW Teesta III hydropower project and severely damaged 520 MW Teesta V and under construction Teesta VI, both NHPC projects in the downstream, in addition to the damage to NHPC’s Teesta Low Dams III and IV. More than 57 people lost their lives and over 7000 people were displaced.[2] Here too local communities had put up very strong protests against Teesta III and dams on Teesta River and warned about GLOF even before the project construction started. Even scientists had pointed out the impending threat of GLOF at this site for years. [3]

Till date no independent report is available about the disaster, its accountability or the lessons to be learned. The report of the National Dam Safety Authority about this disaster is not in public domain, nor was it even mentioned in the minutes of the Expert Appraisal Committee on River Valley Projects that cleared the reconstruction of the project based on the same old failed EIA done before 2006.

Even as more and more glaciers are receding, glacial lakes expanding and posing a threat, more and more hydropower projects are being built in the headwater regions of Himalayan rivers. This is directly putting local communities and dam workers in the harm’s way. Accountability surrounding these disasters is so severely lacking that after the collapse of Teesta III dam, a new dam was recommended environmental clearance with the same old failed EIA which played an important role in its collapse.

In this situation, what is the role of the governing bodies? What is their accountability in such disasters? How are new projects planned and sanctioned in the headwaters? What are the precautions being taken and studies being done?

Let us take an example of Chenab Basin in Himachal Pradesh and the Union Territory of Jammu and Kashmir where a cascade of over 20 large hydropower dams is planned, being given environmental clearance, are under construction or in operation.

Receding glaciers, expanding glacial lakes and rising threats in Chenab Headwaters

Almost all glaciers in the Chandra and Bhaga basin which make up the headwaters of Change are receding. A study published in Current Science in 2020 states, “most of the glaciers in the Bhaga Basin have experienced critical thinning and lost huge ice mass in the range –6.07 m.w.e. (‘meters water equivalent’) to –9.06 m.w.e.”[4]

In the projected climate, Chandra basin is likely to retain only 40-50% area of glaciers by the end of the century. Volume of glacier water retained will be much lower at between 29-40%, but the volume loss could be as high as 97% for low altitude glaciers.”[5]

Chandra Basin is home to the largest glacial lakes in Himachal Pradesh known as Samudra Tapu Glacial Lake which has expanded by a whopping 905% from 1956 to 2022 from 14.19 ha to 142.69 ha. NRSC-ISRO (National Remote Sensing Centre-Indian Space Research Organisation) report states. “Such alarming rate of lake expansion has increased the possibilities of a catastrophic impact due to GLOF event by many folds.”

It is also home to the largest glaciers in Himachal Pradesh known as the Bara Shigri, (28 km long, 3 km wide with 131 sq kms in area) which is receding rapidly and has lost about 4 sq kms area in the last century, with accelerated loss in the latter part of last century.[6] According to IPCC’s (Inter-governmental Panel on Climate Change) Fourth Assessment Report[7], Bara Shigri’s snout shows a retreat of 650 meters between 1977 to 1995, averaging to 36.1 meters retreat annually.

More than 60 ice-dammed (supraglacial) glacial lakes have formed on the debris covering the glacier.[8] These lakes are highly susceptible to climatic changes.

The most dangerous glacial lake in Chandra Basin is the Ghepan Gath Glacial Lake near Sissu. The NSRC-ISRO states: “A change analysis of the lake water spread area carried out in 1989 and 2022 reveled a 178% increase in size from 36.49 ha to 101.30 ha. Such alarming rate of lake expansion and the rapid urbanization of its downstream settlements have increased the possibilities of a catastrophic impact due to GLOF event by many folds.”

Leading glaciologists like Ashim Sattar whose team warned against the Sikkim GLOF have called attention to artificial lowering of Ghepan Gath Lake. The authors state that even after the proposed lowering of 30 meters, “It is seen that there is a significant reduction in the GLOF impact downstream when the lake levels are lowered, but the risk from very large events is not eliminated.”[9]

And yet, newer agreements are being signed about hydropower projects in this region, ignoring local protests.[10]

CWC, Hydropower Projects and GLOFs

In this situation, how is CWC (Central Water Commission, India’s premium technical body on water resources), whose representative also sits in the MoEF&CC’s (Ministry of Environment, Forests and Climate Change) Expert Appraisal Committee for River Valley Projects, a body which recommends Environmental Clearance to hydropower projects, assessing GLOF risks? What does it recommend when a hydropower project is in the path of a possible GLOF? CWC representative also sits on a committee of CEA (Central Electricity Authority) that gives Techno-Ecnonomic Clearance to all large hydropower projects.

Let us look at a paper being authored by the Director, Deputy Director and Assistant Director of CWC dealing with the impact of GLOF on Dugar Hydropower Project in the Pangi Valley across Chenab.

This paper has been presented in 2022 at the International Conference on Hydropower and Dam Development for water and energy security under changing climate[11] titled ‘A Comparative Modelling Study of Glacial Lake and Associated Glacial Lake Outburst Floods at Dugar Hydro-Electric Project in Chenab River Basin.’

- Firstly, the authors are trying to assess the impact of GLOF generating in the farthest upstream Glacial Lake on the last dam in the cascade of hydropower projects in Himachal Pradesh at a distance of over 205 kms. There are over 20 large hydropower projects planned on the Chenab mainstem upstream of Dugar, much closer to the high-risk glacial lakes, but the authors assess the impact on the farthest project.

- The study undertakes ‘vulnerability analysis’ and decides to study the impact of three glacial lakes and consequent GLOFs on Dugar HEP. For some reason, names of the three glacial lakes which have been used for generations are not mentioned. These names are also used by several studies, so it is unintelligible why only “Lake Ids used by CWC” are used. Incidentally, CWC uses two different lake IDs for the same lake. To add to the confusion, the coordinates of one of the glacial lakes (Ghepan Gath) used in the paper are incorrect. The coordinates, when traced, lead to a mountain peak!

However, after plotting the coordinates it is clear that the glacial lakes considered by CWC are:

| Lake ID used in the Paper | Lake Name | Comment |

| 01_52H_002 | Ghepan Gath Glacial Lake | Wrong coordinates used in the paper |

| 01_52H_004 | Samudra Tapu Glacial Lake | CWC Inventory Lake ID also labels this lake as 01_52H_003 |

| 01_52H_005 | Chandra Tal | Chandra Tal is not considered as a high-risk glacial lake by other studies. |

- Volume of Samudra Tapu Glacial Lake calculated by CWC as compared with other publication is very different.

While CWC paper (2022) assesses the volume to be 17.6 MCM (Section 3.2, Page 4), other studies including those by authors from National Institute of Hydrology and an NSRC-ISRO report titled ‘GLOF Risk Assessment of Samudra Tapu Glacial Lake in Indus River Basin’, assesses the volume to be 57.5 MCM. Even an earlier, 2017 study assess the volume to be 67.7 MCM. Some other assessments are even higher. The reasons for this three-fold difference are unclear.

500 MW Dugar Hydropower Project has been recommended Environmental Clearance in August 2022 based on these and calculations and recommendations.[12]

| Agency that assessed volume of Samudra Tapu Glacial Lake | Volume in MCM | Source | Year of assessment/ presentation |

| CWC | 17.6 MCM | Paper presented in 2022 | 2022 |

| NRSC-ISRO | 57. 5 MCM | NRSC-ISRO | 2024 |

| Authors from National Institute of Hydrology and National Centre for Polar and Ocean Research | 67.7 MCM | Patel et al, A geospatial analysis of Samudra Tapu and Gepang Gath glacial lakes in the Chandra Basin, Western Himalaya, | 2017 |

| Authors from Wetlands International South Asia | 65.34 MCM | Ganapathi et al, ASSESSMENT OF GLACIAL LAKE OUTBURST FLOOD IN CHANDRA BASIN, WESTERN HIMALAYAS | 2023 |

- Differences in Peak Discharge downstream the GLOF site

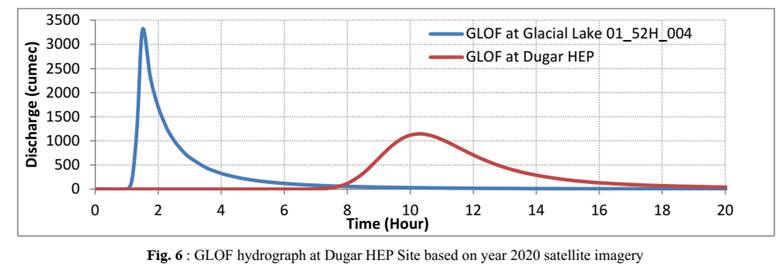

Peak discharge just downstream after GLOF event stated in CWC paper and NRSC-ISRO report are also entirely different. According to the CWC paper using 2020 data, peak discharge is 3305 cumecs[13].

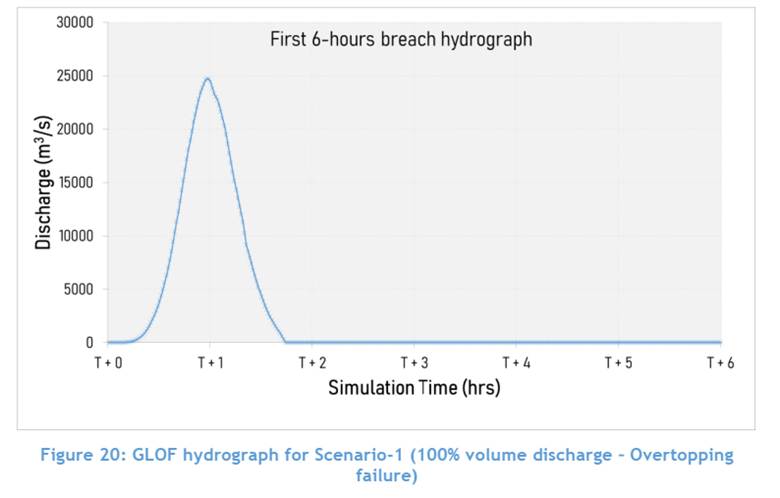

However, according to NRSC-ISRO Report, the peak discharge is 24,730 cumecs for 100% release.

This also leads to very different water depth figures. These have direct implications for settlements like Batal immediately downstream the glacial lake.

Above: From CWC 2022 Paper

This is such a huge difference that it raises huge questions about the accuracy of all further calculations.

- NRSC ISRO study also considers a scenario when Samudra Tapu and Ghepan Gath Glacial Lakes breach simultaneously under a Probable Maximum Precipitation (PMP) scenario. It is not a far-fetched assumption. As multiple studies have pointed out, both lakes are at a high risk and are very susceptible to changes. Such a simultaneous scenarios has not been considered by the CWC study.

- Finally, although EIA of Dugar HEP mentions CWC’s GLOF study in its EIA report, it is unclear if the spillway capacity is increased to accommodate this flow or not. Dugar HEP has already been recommended for Environmental Clearance by the EAC in August 2022 where CWC is also represented.

- Importantly, major volume of GLOF constitutes sediment scoured from the riverbed and banks as it gains momentum. In case of South Lhonak lake in Sikkim, while the water drained was about 50 MCM, the GLOF eroded ~270 million m3 of sediment and triggered 45 secondary landslides. This adds immense volume reaching the downstream hydropower projects. The CWC study makes no mention of the sediment and its impact on the proposed hydropower projects on the way and on Dugar HEP.

- There are several high-risk glacial lakes developing much closer to Dugar HEP in addition to Samudra Tapu or Ghepan Gath lake which are nearly 200 kms away from the dam site. In a paper rightly titled, “Intimidating Evidences of Climate Change from the Higher Himalaya: A Case Study from Lahaul, Himachal Pradesh, India’[14] authors from institutes like Birbal Sahni Institute of Paleosciences and ISRO report a new lake exponentially expanding just upstream the proposed Purthi Hydropower project on Chenab. This lake is just about 30 kms upstream of the proposed 500 MW Dugar HEP.

- The CWC study and EIA or EAC discussions also do not take into account the cumulative impact of discharge/ disaster in the cascade of proposed hydropower projects upstream of Dugar HEP.

The authors did come up with a newer presentation in 2023 with updated figures, but the peak discharge is still less than NRSC ISRO study, Dugar EIA used the earlier figures by CWC and studies before CWC 2022 study had calculated higher volumes of the lake in 2017 itself.

On more paper presented by CWC at the same conference (International Conference on Hydropower and Dams Development for Water and Energy Security – Under Changing Climate from 7th to 9th April 2022 at Rishikesh) titled: ‘Estimation of Glacial Lake Outburst Flood (GLOF) for Planning and Design of Hydroelectric Projects in the Himalayas’ considers case study of 168 MW Sirkari Bhyol-Rupsiabagar HEP in the Gori Ganga basin of Uttarakhand. Shockingly, the paper does not make any comments, recommendations or suggestions about the design or siting of the proposed project! How is this credible or helpful? The paper relentlessly justifies hydropower projects in the Himalayas without objectively weighing the pros and cons of the situation to arrive at an informed decision. While mentioning the Chorabari GLOF and Uttarakhand floods in 2013, it talks about the damage to hydropower projects but does not make even a fleeting mention of the impacts of these projects on the communities as highlighted by Vishuprayag Hydropower Project. Blockage of the river caused by this project resulted in the river diversion which destroyed Lambagad Village market, which has not returned to normal till date. [15]

The intention of this piece is not to pick holes in the CWC papers but to indicate that the GLOF threats faced by communities in the Chenab basin and overall Indian Himalayas is too large. We are aware that development of new glacial lakes, increase in volume of existing lakes is taking place at a very rapid pace. All the more the reason why Premier institutions like CWC need to integrate cutting edge research of several scientist teams in the country and integrate them with the hydropower development planned and existing in the basin.

There is a very real and urgent need to understand the impacts of GLOFs on the existing, under construction and planned hydropower projects across Himalayas. This assessment cannot be piecemeal, but an extensive undertaking with multidisciplinary experts and local participation.

We have already lost several lives to the Climate change-GLOF-hydropower nexus. It is high time we not only fix accountability of these disasters, but also proceed in a way that values the lives of construction workers and local communities who are left destitute after GLOF and hydropower collapse instances.

Parineeta Dandekar, SANDRP (parineeta.dandekar@gmail.com)

SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION:

2018: CWC came up with Guidelines for Mapping Flood Risks Associated with Dams in 2018, but this important document did not even mention glaciers or glacial lakes.

2020: NDMA came up with a COMPENDIUM OF TASK FORCE REPORT ON NDMA GUIDELINES MANAGEMENT OF GLACIAL LAKE OUTBURST FLOODS (GLOFs) in which it stressed the need for an overarching agency which can function as a Centre for excellence around glacier studies. Nothing of the sort was done.

2021: Rishiganga Valley Disaster. Local communities had protested and even filed cases against hydropower projects which collapsed and caused deaths.

2023: South Lhonak Glacial Lake disaster. 1200 MW Teesta III Dam destroyed. Teesta V and VI damaged. Loss of over 55 lives.

2023: After the South Lhonak Lake disaster, several questions were raised about GLOFs in the Parliament and a Parliamentary Standing Committee submitted its report in December 2023 about ‘Glacier Management in the Country – Monitoring of Glaciers / Lakes Including Glacial Lake Outbursts leading to Flash-Floods in the Himalayan Region’[16]. It highlighted the need for a dedicated agency, “The Committee are of the considered view that given the strategic role and importance of glaciers as a vital national resource, there is a critical and imperative need as never before, to formulate new strategies for combating the challenges posed by the climate change and global warming in the glacier management especially glaciers movement, glaciers surge, Glacial Lake Outburst Flood (GLOF), Landslide Lake Outburst Flood (LLOF) and cloud burst in mountainous regions. In this regard, the role of planners, scientists and academicians assumes critical importance in devising, developing and implementing suitable measures for studying, monitoring and providing early warning response to reduce the potential glacier related risks. Fragmented research and studies by various Departments/Institutions/Agencies in this regard will not yield desired results / outcomes and also may not necessarily convert into actionable steps. The Committee, therefore, recommend that there is need to set up a single nodal agency for bringing out synergies among various Government Departments/Ministries involved in glaciological research and monitoring to achieve desirable results. Such an agency should be entrusted with the responsibility of coordinating the activities of all the Departments/Agencies involved in Himalayan Glaciers monitoring and research work.”

However, till date such an agency is not being formed.

Central Water Commission (CWC) monitors 902 Glacial lakes and water bodies, to enable the detection of relative change in water spread areas of Glacial lakes and water bodies as well as identifying those ones which have expanded substantially during its monitoring months. It produces monthly monitoring reports of selected glacial lakes and water bodies between the months of June to October and annual reports every year since 2016. These can be found at https://cwc.gov.in/en/glacial-lakeswater-bodies-himalayan-region It is not clear how these studies are leading to any action plan and providing inputs for decision making process. The quality of these efforts also need to be assessed.

The National Remote Sensing Research Centre-ISRO under the National Hydrology project has been producing reports on High-Risk Glacial Lakes.

Wadia Institute of Himalayan Geology[17] monitors glaciers and has prepared inventories for Uttarakhand (2015) and Himachal Pradesh (2018), identifying 1,266 lakes (7.6 km²) in Uttarakhand and 958 lakes (9.6 km²) in Himachal Pradesh.

2024: PIB Press Release of August 2024 states that “As per the information compiled by NDSA, 47 dams (38 Commissioned and 9 under construction dams) have been identified by Central Electricity Authority under Ministry of Power, which are likely to be affected by Glacial Lake Outburst Flood (GLOF) from the Glacial lakes in the Indian territory. GLOF studies have been completed for 31 projects.” However, no further information of how these dams were identified, what measures are recommended and what sort of GLOF studies are completed is clear.

2025: As per PIB press release on the 1st of April 2025, Central Government has approved National Glacial Lake Outburst Flood (GLOF) Risk Mitigation Project (NGRMP) for its implementation in four states namely, Arunachal Pradesh, Himachal Pradesh, Sikkim and Uttarakhand at a financial outlay of Rs. 150 crore.

However, this is still on a project basis and falls woefully short of the recommendation of the Parliamentary Standing Committee and NDMA of instituting an independent Apex Body for studying and mitigating GLOFs.

It is high time that a detailed GLOF assessment of all dams planned in GLOF watersheds is conducted by an independent body and an apex body as suggested by the Parliamentary Standing committee is constituted without losing any further delay. It may be added that CWC cannot be the apex body in this regard, considering its track record.

[1] GLOF Risk Assessment of Ghepang Ghat Glacial Lake in Indus River Basin, NRSC-ISRO 2023

[2] Sattar et al, The Sikkim flood of October 2023: Drivers, causes, and impacts of a multihazard cascade, 2025, https://india.mongabay.com/2025/02/political-stir-follows-expert-panels-approval-to-rebuild-teesta-dam-in-sikkim/

[3] Sattar et al, Future Glacial Lake Outburst Flood (GLOF) hazard of the South Lhonak Lake, Sikkim Himalaya, 2021

[4] Nagajyothi et al, Western Himalaya: a geospatial and temperature-weighted AAR based model approach, 2020

[5] Tawde et al, An assessment of climate change impacts on glacier mass balance and geometry in the Chandra Basin, Western Himalaya for the 21st century, 2019, Environmental Research Communications

[6] Pritam Chandra Sharma, 2017, Reconstructing the pattern of the Bara Shigri Glacier fluctuation since the end of the Little Ice Age, Chandra valley, north-western Himalaya,Progress in Physical Geography, Earth and Environment

[7] Climate Change 2007: Working Group II: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability, IPCC

[8] Chander Prakash et al, IIT Mumbai, 2018 Glacial lake changes and outburst flood hazard in Chandra basin, North-Western Indian Himalaya

[9] Sattar et al, Modeling Potential Glacial Lake Outburst Flood Process Chains and Effects From Artificial Lake-Level Lowering at Gepang Gath Lake, Indian Himalaya, 2023

[10] https://www.tribuneindia.com/news/himachal/pact-on-two-hydel-projects-in-lahaul-spiti-faces-opposition/

[11] https://www.cbip.org/ISRM-2022/images/7-8%20April%2022%20Rishikesh/Data/Session%204/2%20Sh.%20Ankit%20Kumar.pdf

[12] https://environmentclearance.nic.in/writereaddata/Form-1A/Minutes/0609202262648832DraftMoM33rdEACRVHEPheldon29_08_2022.pdf

[13] https://www.cbip.org/ISRM-2022/images/7-8%20April%2022%20Rishikesh/Data/Session%204/TS4-2.pdf

[14] https://www.researchgate.net/publication/370036808_Intimidating_Evidences_of_Climate_Change_from_the_Higher_Himalaya_A_Case_Study_from_Lahaul_Himachal_Pradesh_India

[15] https://www.downtoearth.org.in/environment/vishnuprayag-hydel-project-suffers-extensive-damage-41610, https://sandrp.in/2013/06/23/uttarakhand-floods-disaster-lessons-for-himalayan-states/, https://sandrp.in/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/drp_june_july2013.pdf

[16] https://sansad.in/getFile/lsscommittee/Water%20Resources/17_Water_Resources_26.pdf?source=loksabhadocs