As somewhat belated summer in North India reaches its peak, with ongoing heat wave in Delhi and surrounding areas, there is increasing fear of water scarcity. The media generally uses one figure to highlight this situation, namely Live Storage in some 150 reservoirs in Central Water Commission (CWC)’s Weekly Reservoir Bulletin (WRB) that is published every Thursday afternoon (why cannot this be given on daily basis is a mystery).

The first thing to note about the water storage position given in CWC’s WRB is that this is expected to be low when we are getting ready to welcome the South West Monsoon (SWM) that has already set in Andaman Sea. In fact according to Bhakra Beas Management Board (BBMB), the reservoir filling period for Bhakra, Pong and Pandoh reservoirs has already started on May 20 and reservoir levels have started rising.

The reservoirs in any case are constructed to use up the water before the onset of next monsoon. In fact optimum utilisation of created capacity would mean that the live storage capacity of the reservoirs should be bare minimum when fresh inflows into these reservoirs start. To have substantial quantity of water in these reservoirs when fresh inflows starts would also be non-optimal as that would mean much less storage capacity in these reservoir for storing fresh inflows. It would also mean increased potential of avoidable flood disasters.

In fact since IMD (India Meteorological Department) has already forecast above normal rainfall in SWM 2024, and since La Nina factor is also likely to be active during the monsoon, which generally brings surplus rains, lower the storages we have at the onset of the SWM, better it is for us.

According to CWC’s bulletin, North India includes Himachal Pradesh, Punjab and Rajasthan. Uttarakhand, which should be in North India, is strangely included in East India. And rest of North India (Haryana, Jammu & Kashmir, Delhi, Chandigarh) is absent since these states do not have any worthy water reservoir to be included in CWC list!

So in North India, CWC bulletin includes ten reservoirs, where the live water storage on May 24 was 5.554 BCM (Billion Cubic Meters) or 28% of total live capacity. This is only 3% below the ten years average figure of 31%, which is defined as Normal. So while this is lower than last year’s or normal storage, it cannot be called alarming. India had 5.55% below normal rainfall in SWM 2023, so some deficit in storage is expected. However, North India also had more than one round of severe floods during SWM 2023, so we need not be having alarmingly low reservoir levels.

The key missing question however here is, does the CWC’s WRB provide an accurate or even widely applicable figures for water available across India? CWC’s WRB includes water storage figures in just 150 reservoirs across India. India has 6138 completed Large Dams as per CWC’s National Register of Large Dams (Sept 2023). Thus CWC’s WRB includes less than 2.5% of India’s Large Dam reservoirs. In terms of storage capacity, it includes larger proportion of Live Storage behind these completed large dams but the key point is that it does not provide the applicable useful information for large majority of Indians as for them it is the smaller local reservoirs and groundwater aquifers that are useful for them, and not some distant mega water body.

If CWC wanted to provide more accurate picture of water stored in India’s reservoirs, it can easily do it, as illustrated by us in 2018 when we wrote about How India measures Water Storages. We showed that state govt websites provide water storage position in 3863 reservoirs across India more frequently and accurately than possibly CWC’s WRB.

In fact India has lakhs of smaller water reservoirs and millions of groundwater aquifers that people depend on, which provide the largest proportion of water India uses, and clearly CWC’s WRB does not provide accurate water availability figure that the vast majority of Indians depend on. BBMB’s reservoirs, for which filling period starts on May 21, in fact gets its water in summer from the melting of glaciers and other snow-mass, which is a different source altogether, for which we have no figures.

But this outdated focus on large dams that the governments in India has been using to neglect all other options has also rubbed onto the media, it seems. The world is realising that this advocacy for large dams is no longer useful. In fact there is increasing movement across the world to decommission Large Dams. With increasing impacts of climate change on rainfall patterns, this movement is only going to gain strength.

Moreover, India in the just concluded year 2023-24 saw one of the lowest generation from large hydropower dams. The number of disasters related to dams and hydropower projects are increasing rapidly. In coming June 2024, when peak power demand will be the highest, hydropower generation is projected to be at the lowest. The Tehri project in North India has added to this bad news by saying power generation from the project will be suspended from June 1. This will also affect water supply in Delhi and UP.

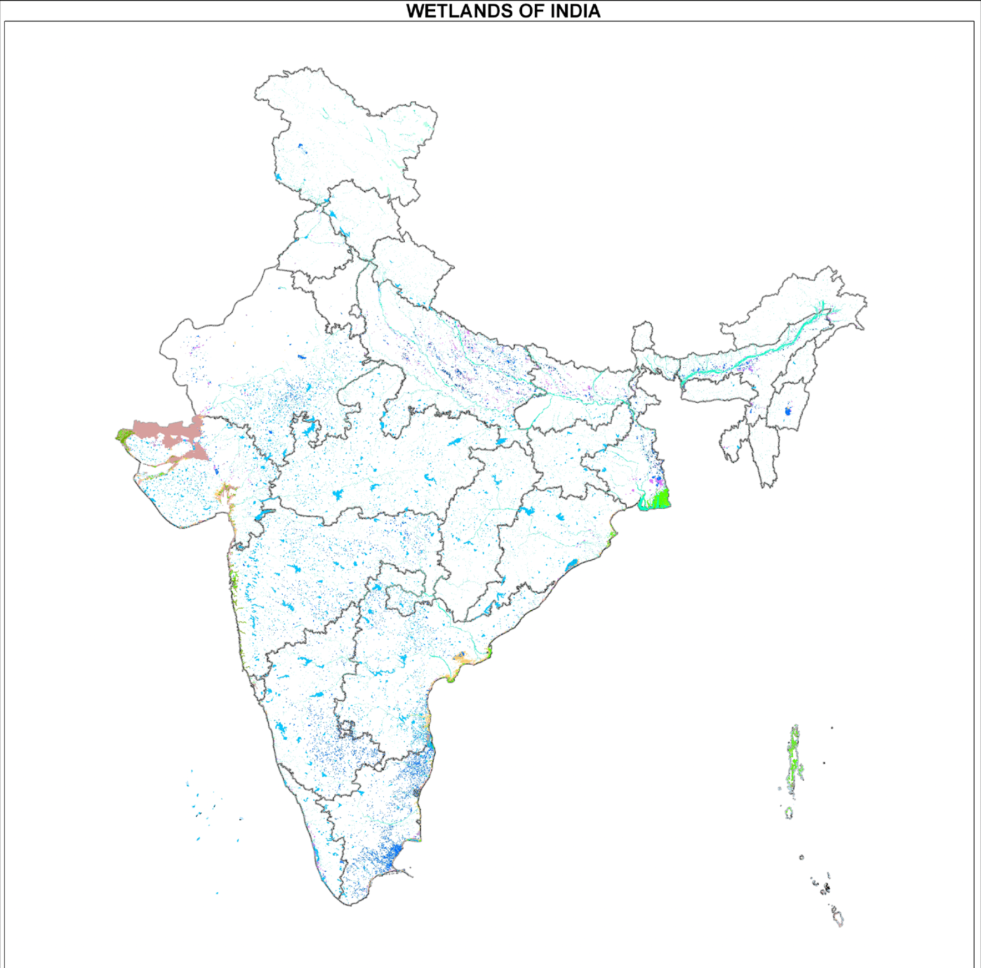

The key question in the context of water scarcity is, what is the most optimal way of maximum harvesting, storage, recharge and utilisation of rains and local flows. The key component to achieve this objective is the catchment of any river or stream. Greater the capacity of the catchment to harvest, hold, store and recharge rainwater at or close to the source, nearer we will be to achieving this objective. This capacity of catchments can be improved, when there are more natural forests, water bodies, more organic or carbon content in the soil, more we are able to recharge the groundwater, more wetlands we have in the catchments, more floodplains we have saved from destruction. The barometer for this is our rivers, streams. If our catchments are healthy, than rivers will have more distributed flows particularly in post monsoon months.

Sponge cities is the name of the scheme for our urban areas in the same context. This scheme is all about harvesting, holding, storing, recharging more proportions of the rain and flow in the city.

Earlier we adopt these measures and commensurate policies and programs, smarter our cities will become, more secure our water future will be.

PS: An edited version of this was published on May 28 2024 at: https://www.tribuneindia.com/news/comment/becoming-water-smart-holds-the-key-to-tackling-scarcity-625429.