Guest Article by Mridhu Tandon [i]

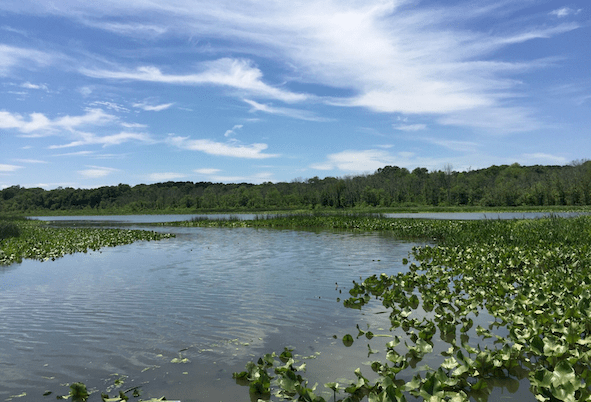

The Sudd wetland in the Nile basin is one of the world’s largest freshwater ecosystems. Nourished by the White Nile-a tributary of the Nile, Sudd is a mosaic of open water and submerged vegetation, seasonally inundated woodlands, rain-fed grasslands, and floodplain scrubland. An integral part of Africa’s largest intact savannahs-the Jonglei plains, Sudd supports the world’s second-largest mammal migration after Serengeti. An estimated 1.3 million antelope: white-eared kob, taing, and Mongalla gazelles move from Sudd every year to reach Ethiopia’s Gambella National Park. Sudd has been in the international news recently. Revival of the 40-year-old 240-mile Jonglei canal will divert the waters of the White Nile around the Sudd wetland and send it to Egypt. The canal will desiccate the wetland, and end seasonal flooding of the Jonglei grasslands. Why is it necessary to protect Sudd from drying up? Why has the subject received global attention? More generally, why protect wetlands at all?

As per the Convention on Wetlands of International Importance especially as Waterfowl Habitat (or the ‘Ramsar Convention’), the world’s rivers, lakes, estuaries, swamps, marshes, flood plains, peat lands, mangroves, seagrass beds, coral reefs are collectively termed as wetlands. This definition also includes marine systems up to 6 meters in depth and human-made wetlands such as rice paddies and water storage bodies. The focus of this article is however restricted to natural wetlands.

The importance of Wetlands These wetlands are ecologically and economically critical ecosystems. They play a key role in the global water cycle by receiving, storing, and releasing water, regulating flows, and supporting life. The riparian vegetation within and around wetlands acts as a buffer, by removing pollutants from both point and nonpoint sources of water pollution, hence purifying the water. Wetlands also provide food supplies such as rice, fish, timber, fuel, and non-timber forest products. An estimated one billion people make a living from wetlands. Wetland tourism and travel support 266 million jobs worldwide. The economic value of ecosystem services provided by inland wetlands alone is five times that of tropical forests.

Wetlands, however, have traditionally been viewed as ‘wastelands’, of low value due to flooding, as well as being sources of mosquitos, flies, unpleasant odours, and disease. From a development perspective, it has been typical to assume that for wetlands to become valuable within current systems, they must be drained to make way for farmlands or filled to construct real estate and industrial facilities. For example, India’s Rural Development Ministry classifies wetlands such as marshes as wastelands in its Wetland Atlas of India, 2019. The report identifies areas such as marshes that can be used to boost agricultural production and develop industrial zones, despite their status as wetlands. Industrialization compromises marshes’ ability to recharge groundwater and serve as prime habitats for the globally threatened fishing cat.

Rapid Decline Due to reclamation and conversion, the world’s wetlands have declined fast. As per the Wetlands Extent Index, 35% of natural wetlands were lost between 1970 and 2015. Over this period, the average annual rate of wetland loss was 0.95%. However, this rate almost doubled in the most recent five years from 0.85% for 2005-2010 to 1.6% for 2010-2015.

These trends are alarming, especially as the world is less than a decade from achieving its goals set under the Paris Agreement and the proposed post-2020 global biodiversity framework, for which wetlands are key.

Wetlands – the best defence against climate change? The 2015 Paris Agreement requires limiting global warming to well below 2 degrees Celsius, preferably to 1.5 degrees Celsius, compared to pre-industrial levels. Achieving this goal would require reducing CO2 emissions by 45% by 2030 relative to 2010, and reaching net-zero emissions by 2050. The 2021 Glasgow Climate Pact underscored the urgency required to achieve this goal, calling for countries to strengthen their own 2030 domestic climate targets and align them with the Paris Agreement goals by the end of 2022.

While the world’s forests are vital in fighting climate change, wetlands may be even more valuable in achieving global climate goals. Coastal wetlands, like mangroves, salt marshes, and seagrass meadows can absorb carbon at a rate 50 times greater than that of terrestrial forests. They also maintain their sequestration rates for centuries, while rates in most forest ecosystems level off after a few decades.

Peatlands Undisturbed wetlands are powerful carbon sinks as well. Coastal habitats can store 3-5 times more carbon per equivalent area than tropical forests. Given their largely anaerobic soil, the carbon in coastal wetlands decomposes slowly and therefore can be stored for up to thousands of years. Further, peatlands occupy only 3% of the world’s land area, yet they store twice as much carbon as the world’s forests. Peatlands can store carbon more effectively and for longer periods than any other terrestrial ecosystem.

However, when developed for alternative usage, these carbon sinks can turn into a major carbon source. Draining peat lands for agriculture and forestry operations leads to the release of CO2. Though only 15% of the total known peatlands have been drained, they alone are responsible for 5% of global CO2 emissions. Once this carbon is lost, it will take centuries to form peat. Peatlands in Congo Basin, New Guinea, Northern Scotland, and the Hudson Bay Lowlands are considered irrecoverable carbon reserves. These are vast natural carbon stores that are vulnerable to release from human activity. If lost, the carbon could not be restored by 2050.

Coastal Wetlands Coastal wetlands too are under pressure and are often developed for housing, ports, and other commercial facilities. Studies suggest that the destruction of vegetated coastal ecosystems will release 0.15-1.02 billion tonnes of CO2 emissions annually, equivalent to 3%-19% of emissions from deforestation globally.

Wetlands are useful beyond controlling emissions. With climate change increasing the risk of coastal flooding, coastal wetlands help in building resilience against this by absorbing the force of incoming waves, providing storm protection, and preventing erosion. Recent studies suggest that existing coastal habitats are more cost-effective than building sea walls in reducing the height of flood waves and thereby protecting coastlines.

Protecting wetlands is therefore an important pathway to mitigating climate change and building resilience to climate-induced vulnerabilities. Safeguarding these biomes as intact natural ecosystems will also be important for conserving the biodiversity within them.

Wetlands-key to conserving global biodiversity? Representatives of 172 countries are meeting this week (5-13 Nov, 2022) in Geneva, Switzerland, for the 14th Conference of Parties (CoP) to the Ramsar Convention. Wetland conservation will be an important subject of discussion. For example, Resolution no. 18.20 recognizes their value as nature-based solutions for climate change mitigation and adaptation. It urges parties to include these solutions in their Nationally Determined Contributions under the Paris Agreement. Parties are also urged to simultaneously address biodiversity loss, wetland degradation, water abstraction, and risks associated with climate change as urgent, and pursue policies to safeguard wetlands in the coming years.

Following the Ramsar CoP, representatives of 195 countries will meet in December 2022 in Montreal, Canada to finalize the post-2020 Global Biodiversity Framework of the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD). This landmark negotiation aims to set long-term conservation goals to be achieved by 2050 and a series of ‘action-oriented’ goals and targets achievable by 2030.

1% surface, 5-11% species Wetlands such as rivers, lakes, peatlands, and swamps alone host an extraordinary diversity of floral and faunal communities. They constitute less than 1% of Earth’s surface, supporting 5% of all plant species and 11% of all animal species, including one-third of vertebrate species. As per the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species, 36,833 species live and breed in wetlands.

Despite their contribution to global biodiversity, wetlands worldwide are undergoing a major biodiversity crisis. On average, populations of wetland vertebrate species have declined by 83% between 1970 and 2018. Of the 36,833 wetland species assessed so far, 21% are threatened with extinction. These trends have largely been driven by changes in wetland extent due to conversion and drainage; construction of dams that reduce flows, sediments, and connectivity; overexploitation of species; and introduction of invasive species and pollutants that affect habitat quality.

Fishy trouble Amphibians, reptiles, and fishes are well documented as being affected by the loss of wetland ecosystems (although of course many other species, such as species of dragonflies, molluscs, and plants are equally seriously threatened). For example, consider the Granular salamander-an amphibian species found in the Highland wetlands of Mexico. This endangered species faces the threat of extinction from invasive predatory fish. In the mid-1990s, the Mexican government began a program to distribute non-native carp for a local fishery project. The project is still in existence. Since the introduction, the population of the Granular salamander has declined by 50%. Riverine fish species such as the Mekong giant catfish also face a high extinction threat. This wetland megafauna can reach a maximum length of 3 meters and weigh up to 300kgs. At the onset of the rainy season, adult Mekong catfish gather in the lower Mekong River and migrate huge distances together to their spawning grounds. The construction of dams over the Mekong has, however, fragmented the catfish habitat and blocked their traditional migration routes. And if the fish stop migrating, they will stop spawning. Furthermore, overfishing in the River has led to a 90% decline in the population of Mekong giant catfish in just two decades. Identified as beingcritically endangered, only a few hundred individuals of the giant catfish are surviving in the wild. The case of the Cuban crocodile is equally noteworthy. Earlier also found in the Cayman and Bahamian islands of Cuba, the species is now restricted to only two swamps of the country-Zapata Swamp and Lanier Swamp. Listed as critically endangered, their range is the smallest of any crocodile. The population of this crocodile species has plummeted by 80% in just three generations. This is mainly attributed to a decline in habitat quality and exploitative illegal hunting for the sale of meat.

The above trends could limit the ability to meet the primary 2050 biodiversity goal as drafted which seeks to ‘enhance the integrity of ecosystems, ‘support a healthy and resilient population of species’, ‘halve the risk of species extinction’, and ‘safeguard 90% of species’ genetic diversity. An important draft target that can help realize the above goal is to protect and conserve 30% of the planet’s land and sea area by 2030. Given the role of wetlands in conserving biodiversity, restricting their conversion could help achieve this vision of reducing biodiversity loss. This vision would also ensure that this biodiversity continues to generate the wealth of ecosystem services that are essential to the livelihoods of local communities.

Conserve wetlands, but how? Conserving wetlands as a pathway to satisfy global climate and conservation commitments starts with ensuring that they are adequately included in global policymaking. Currently, wetlands are under-represented as compared to other ecosystems. For example, as a part of the Glasgow Pact, 141 countries pledged to halt and reverse forest loss by 2030. Since 1970, natural wetlands have disappeared three times faster than forests, and populations of wetland species have fallen at more than twice the rate of land or ocean vertebrates. Yet, no similar promises were made to save wetlands. Even in terms of conservation strategies, there exists no framework that can guide policy actions commensurate with the scale and urgency of the wetland biodiversity crisis. And actions taken till now to safeguard wetlands have largely been inadequate.

Six Priority Actions to stop wetlands loss The proposed Global Biodiversity Framework should therefore address wetland biodiversity decline better. Draft target 3 of the framework seeks to enhance the protected area coverage and conditions across terrestrial areas and marine areas. And this currently includes wetlands within the terrestrial category. However, to effectively address threats to wetland biodiversity, the framework must specifically reflect actions to correct threats that affect its water flow and connectivity. The world’s leading wetland scientists have identified six priority actions to bend the curve of wetland biodiversity loss. These include the following- accelerating the natural flow in wetlands; reducing pollution; protecting critical wetland habitats; ending overfishing and overexploitation of species; preventing the introduction of invasive non-native species; restoring connectivity between upstream and downstream river stretches, and between rivers and floodplains. The targets proposed under the post-2020 framework should therefore either be amended or re-drafted to reflect the wetland priorities. And indicators must be specified to guide the implementation of these targets.

Dams destroy wetlands Domestic decisions on wetland use should also consider the uniqueness of these biomes and prioritize the urgency to protect them. For example, consider the Lower Mekong Basin which is spread across four countries-Cambodia, Thailand, Lao PDR, and Vietnam. As of 2019, 89 dams were constructed in the lower basin with 44 more in the pipeline. Next time when the national governments decide to give permits to build another dam, the authorities should deliberate (or invite experts who can advise) over whether the new dam would further block the migratory pathways of the riverine fauna. And if yes, whether the fish would be able to swim across a large barrier like a dam to reach its spawning grounds upstream. Without these norms, commitment to international agreements is ineffective.

Wetlands should be considered as separate land use category in official records As the world gears up to finalize the Global Biodiversity Framework, few NGOs are advocating for a better representation of wetlands in the targets. For example, The Nature Conservancy (TNC) has recommended explicit recognition of wetland ecosystems in draft Target 1 which seeks to cover all land and ocean areas under integrated biodiversity-inclusive spatial planning. WWF has called for better representation of rivers and other inland waters in Target 2 on ecosystem restoration. TNC has also called for the specific inclusion of wetlands in draft target 3 Furthermore, Wetland International is calling for increasing the area of certain wetlands before 2030- mangroves by 20% and tidal flats by 10%. However, how is it possible to register an increase in wetland areas if they are not recognized as a distinct land-use category in the land records of the country? Forests often have a distinct place in the land records, however, wetlands are often ignored or even bundled under the ‘wasteland category’. Therefore, the foundation for conserving wetlands domestically lies in enlisting them as a separate category in the official records.

Saving these natural assets requires targeted efforts. Administrative authorities at the domestic level and those in charge of global climate and conservation agendas need to act now. Otherwise, as the Sudd case shows, the implications can be extreme: Sudd has approx. 16,000 sq. km of peatlands which holds up to 4 billion tons of carbon. The monetary value of the wetland for providing natural resources, regulating river flows, and cultural and biodiversity benefits are estimated at $ 3.3 billion. All this will be lost if water abstraction from Sudd is permitted. Wetland advocates have even questioned the credibility of Egypt as the host for the current climate negotiations as it proposes the completion of the Jonglei canal. Given that the world is nowhere near stemming the tide of wetland decline, the choices, therefore, seem clear: investments and policies to protect wetlands are urgently needed now.

Mridhu Tandon (mridhutandon@gmail.com)

NOTE: The author is an independent conservation researcher based in New Delhi, India. She is also a member of the IUCN-World Commission on Protected Areas (WCPA).

END NOTE:

[i] Sincere gratitude to Dr. Ian Harrison, Freshwater Specialist at Conservation International & co-Chair of the IUCN Species Survival Commission’s Freshwater Conservation Committee, and Dr. Rachel Golden Kroner, AAAS Science and Technology Policy Fellow at USAID for their mentorship and comments on the previous version of the article.