Guest Article by Dr. Sreeja KG and Dr. Madhusoodhanan CG

Climate change and its impacts in the tropics are changing the once familiar landscapes, once certain weather patterns, once secure living spaces beyond recognition. The disasters that can be as local as a tidal surge to national level episodes of cyclones, wildfires and massive floods are being managed in the same administrative mode as has been the practice during the more forgiving past: without training, without relevant real time information, without involvement of the communities and often merely with the strong will and dedication of the field staff and local volunteers. With events far in between, episodic and with time to recoup, we have been spared total and irrevocable breakdown of the system and society. But for how long?

Last year we had written about the everyday realities of a changing climate on our second season paddy crop and the state of our recalcitrant administration at all levels of governance[i]. We slowly recovered from our losses, planted a summer crop of blackgram that served as a balm during the worst days of Covid, lost half of the crop to floods from Cyclones Tauktae and Yaas in May of 2021[ii], again discounted losses, counted our blessings and prepared for yet another second season paddy crop in August. This time around the calamity visited early in the cropping season; as the SW monsoon was making a courteous exit. Least expected and most damaging, as has become the norm in this age of climate crisis. We shared this in our last guest post — last year’s paddy crop was hit by a surprise shower at the time of harvest in January 2021.

A dear friend of ours had decided to farm this year on our land. A self-taught farmer, he had been wanting to try his hand at midland paddy cultivation for a while. It was sheer pleasure to see him and his work partner earnestly take up each stage of land preparation, arranging for seeds and nursery laying, building local relationships, and slowly settling in with the rhythm of the land and its ways. They had decided to go for a transplanted crop. The SW monsoons which was in its final legs went rogue in the last few days, barely two weeks after the crop was planted in the field.

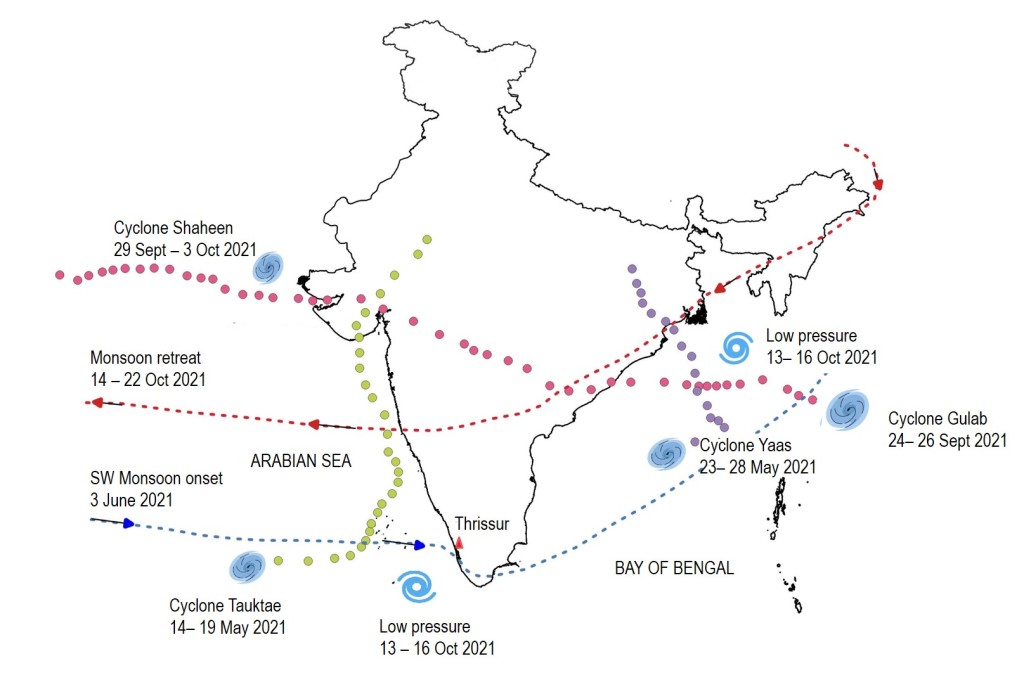

A transplanted paddy crop is more capital and labour intensive. You spend more time, energy and money on all pre-cultivation operations from field clearing and preparation to bund strengthening. But transplanted crop also gives you some leverage when it comes to planting and plant establishment and promises higher yields. In fact, we could delay the actual transplantation for a day or two when rains brought in by the cyclone Gulab in the Bay of Bengal interfered with the plans for transplanting in the last week of September. (Cyclone Gulab, in a rare feat, then crossed over the Indian mainland, entered the Arabian Sea, and with a new name Shaheen moved towards the Persian Gulf to wreak havoc in middle-east Asia). When the seas calmed and skies cleared, the paddy was transplanted from the nursery.

This year the entire polder got together to establish the seedling nursery and had decided to plant a single variety on the same date. This kind of synchronisation, though not easily achieved, helps in water management and lower machinery renting costs. Nonetheless, Gulab-induced rains had increased the water levels in the Peechi reservoir and created a nearly bankful flow in the Manali river. We were having trouble with waterlogging in the fields at the end of the watershed bordering the stream which too was flowing full. When two low pressure depressions one each in the Arabian Sea and the Bay of Bengal developed following the Typhoon Kompasu in the South China Sea, rains resumed with a vengeance over Kerala, from October 11th onwards (Figure 1). On our farm, the stream bunds overtopped, water flowed into the planted fields and sunk the barely a fortnight old transplanted seedlings deep under water.

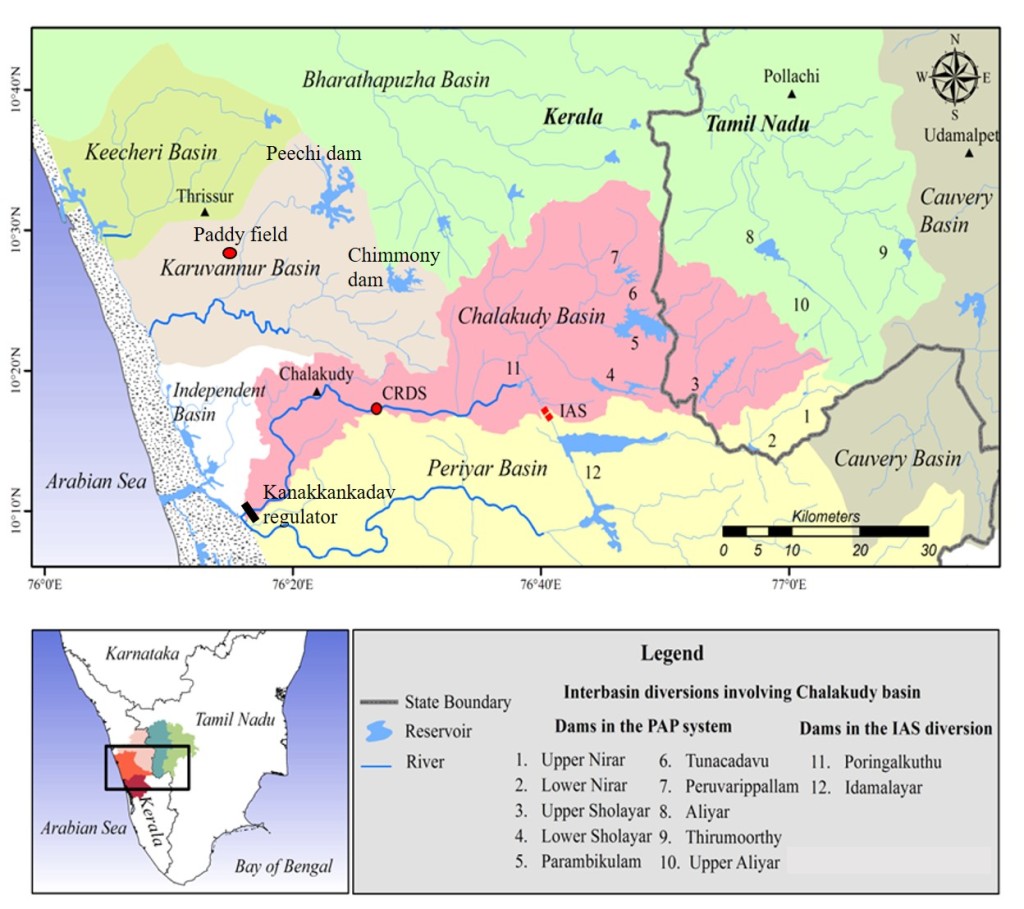

As it was already approaching the end of a fairly good SW monsoon season and after the impacts of the cyclone twins Gulab and Shaheen, many reservoirs in the state were already skirting Full Reservoir Levels (FRL). In the nearby river basin of Chalakudy, the water levels in its upstream dams were rapidly rising. The Tamil Nadu (TN/ Upper) Sholayar reservoir was already above FRL and the Parambikulam reservoir was nearing FRL. The Tamil Nadu state, who owned and operated both these dams as per the PAP treaty[iii], was consistently and erroneously reporting the storage at TN Sholayar as exactly 100% against the actual figure which was well above 100%, to the Central Water Commission (in their Reservoir Level & Storage Bulletin published weekly on every Thursday) [iv].

In this age of aggravated climate uncertainty, dams are increasingly releasing spills from rapidly filling up reservoirs during extreme, intense and unprecedented rainfall events[v]. It is terrifying that there is no mechanism in the country to verify such dangerous manipulations of reservoir storage records which could end up creating manmade floods and havoc downstream. The sudden increase in the water level at the Parambikulam dam due to heavy rains and abrupt release of water from an overfull TN Sholayar dam resulted in an unexpected release of a large quantum of water from the Parambikulam dam in the early hours of 12th October 2021 (2.30 am).

Since there were no official warnings or prior notices to the Kerala government on this surprise release, no warnings could be issued to the downstream population in the Chalakudy basin (see in Fig 2 above a map showing the locations of various components described in this article). Because of the lack of warning, the regulator shutters downstream of the Chalakudy river at Kanakkankadav which discharges flood waters into the Arabian sea were also partially closed. As the huge spill released without any warning from these two upstream dams rushed down the Chalakudy river after midnight, it could have been the making of a huge downstream disaster which was averted only because of dedicated community-driven monitoring initiatives downstream. Since the administrative system could not plan for the lifting of the shutters at the Kanakkankadav regulator on time, a local fish worker had to take up the risky task in the pouring rain on October 12th morning, at the last minute, avoiding unimaginable downstream calamities[vi]. Following this shocking water release, the Chief Secretary of Kerala state wrote to his Tamil Nadu counterpart to ensure adequate flood cushion at Parambikulam reservoir to avoid such future incidents.[vii]

The rains retreated for a couple of days and intensified by October 16th Saturday, especially over central and south Kerala, triggering numerous landslides and flash floods. It was decided to release water from many of the state’s nearly full reservoirs in preparation for more rains predicted due to the retreating monsoons arriving by October 20th. The Peechi and Chimmony dam shutters were thus raised on 16th October 2021, which sealed the fate of this year’s crop once and for all.

The newly transplanted seedlings have been inundated now for close to two weeks. As the river level continues to be high, the water from the paddy fields, which are in fact floodplains, would take more time to withdraw. When it rains in such extreme intensities, it is frightening to witness the rush of water from the increasingly built-up catchments of our stream into our polders[viii]. These midland paddy fields had once provided invaluable flood containment spaces across the state. With their drastic conversion over the years (refer previous article), now 20% of the original area has to contain downpours which on the other hand have increased in intensity. The state received 135 per cent excess rains during the period from October 1 to 19 (117% excess by Oct 24, 2021[ix]) according to the India Meteorological Department (IMD)[x]. It is to nominally pay for this priceless ecological service that the Govt. of Kerala initiated the Royalty scheme for paddy lands retained as wetlands. The amount though of Rs 2,000 per hectare is a highly insufficient incentive, given the increasing importance of these lands in these times of climate crisis.

An unprecedented move by the Peechi dam authorities this time over was to open the outlets of the river into the ‘Kole’ paddylands where this year’s paddy season is yet to start. The Kole wetlands[xi] thus literally became floodwater sinks. This is exactly the kind of administrative resilience and agility that is expected in climate crisis times. Unfortunately, these still remain emergency modes of working, preventing such measures from being participatory with community support. Rather, resources are commandeered at the last hour that leads to unnecessary conflicts that could have been avoided with systematic steps to invite and include communities and stakeholders in disaster preparedness and management.

It is 26th October today. IMD has predicted that the retreating monsoon rainfalls would continue till early this week. We would have to wait that out too before replanting this year’s crop. Meanwhile paddy seeds are in short supply with frantic demand from all those who lost their crop across the state. We have no idea what awaits us at the end of the cropping season that would now restart a month late. It could be an early and harsh summer signalling water crisis for the crop in its ripening stage or more unexpected rains in just the wrong week as it happened last year. These are the small but terrifying ways in which larger agricultural and food crises are unfolding across the country and the tropics.

Dr. Sreeja KG and Dr. Madhusoodhanan CG (kg.sreeja@gmail.com)

END NOTES:

[i] https://sandrp.in/2021/01/14/paddy-farming-in-times-of-climate-change-field-notes/

[ii] https://summerrainweb.wordpress.com/wisdom-of-the-farmer/

[iii] The west-flowing Chalakudy river basin in the Western Ghats has six dams in its upstream, four of which are owned and operated by the Tamil Nadu state as part of the interstate Parambikulam Aliyar project (PAP). Of these four, three including the Parambikulam dam are in Kerala territory and the fourth, the Tamil Nadu Sholayar dam is in the Valparai region of Tamil Nadu just across the border from Kerala. The fifth dam, the Kerala Sholayar, owned and operated by the Kerala state, is below TN Sholayar dam within Kerala. The waters from the Chalakudy river are being diverted into the eastern plains of Tamil Nadu, as per the PAP treaty, but the reservoir spill releases from all the dams are released into the Chalakudy, almost always without prior notice. There is only one other dam in the Chalakudy river outside of the PAP treaty viz. the Poringalkuthu, downstream of the PAP group of dams. To know more of the PAP treaty and the complex water diversions it involves and their impacts please read the book, Tragedy of Commons: The Kerala Experience in River Linking, published by RRC & SANDRP.

[iv] http://www.cwc.gov.in/reservoir-level-storage-bulletin

[v] https://sandrp.in/2021/05/31/drp-nb-31-may-2021-worrying-dam-water-storage-at-the-onset-of-sw-monsoon/

[vi] https://www.thehindu.com/news/cities/Kochi/a-community-resource-centre-on-alert-against-rain-fury/article37101103.ece

[vii] https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/kochi/ensure-flood-cushion-in-parambikulam-kerala-to-tamil-nadu/articleshow/87198922.cms

[viii] Polder is a Dutch word originally meaning silted-up land or earthen wall, and generally used to designate a piece of land reclaimed from the sea or from inland water.

[ix]https://hydro.imd.gov.in/hydrometweb/(S(tdwm5lfcs1eo5145jxkqpmef))/PdfReportPage.aspx?ImgUrl=PRODUCTS\Rainfall_Statistics\Cumulative\District_RF_Distribution\DISTRICT_RAINFALL_DISTRIBUTION_COUNTRY_INDIA_cd.PDF

[x] https://www.indiatoday.in/india/story/kerala-received-135-extra-rain-this-month-says-imd-1866675-2021-10-19

[xi] The Kole wetland system is located 2-3 meters below mean sea-level, contiguous with the Vembanad estuary. Paddy is cultivated only during summers by pumping out water from the polders which are protected by earthen embankments. The Vembanad-Kole wetland is the second largest of the Ramsar sites in India after the Sunderbans.

I am from Jammu and Kashmir. Here also the paddy crop is severely affected due to heavy rain and hailstorm at the time of harvesting season. The standing crops as well as harvested paddy was damaged due to untimely rain n hailstorm. R. S Pura considered as producer of Basmati Rice was heavily affected by it. At many places in R.S Pura there is 80 percent damage of paddy crop.

LikeLike

Many thanks, Dr Bala, for sharing this. Very sorry to know that. Global warming induced rainfall and other seasonal changes are doing havoc to so many farmers. Do keep sharing your feedback.

Himanshu Thakkar

LikeLike