Above: Mithi River at Bandra-Kurla Complex; Photo by Nidhi Jamwal

Guest blog by Nidhi Jamwal

The four rivers of Mumbai —- Mithi, Oshiwara, Dahisar and Poisar —- now have an anthem of their own. Released recently by T-Series and Leelaa, the music video, “Mumbai River Anthem”, has already created uproar in the state Assembly, as it features the state chief minister (CM), Devendra Fadnavis; the state finance minister, Sudhir Mungantiwar; Mumbai civic commissioner, Ajoy Mehta; and the city police commissioner, Datta Padsalgikar lip-syncing and striking poses to urge Mumbaikars to come together to save the rivers. The anthem also features Amruta Fadnavis, wife of the chief minster, who, along with Sonu Nigam, a playback singer, has sung the song. While celebration of rivers is welcome, when not accompanied by necessary actions to improve the pathetic state of Mumbai’s rivers, it sounds like hypocrisy.

The people concerned about the state of Mumbai’s rivers and Opposition have raised several questions over the river anthem video — its funding, the use of CM’s official bungalow, not understanding difference between a lake and a river, etc. But, none of the political parties or people’s representatives have asked real and tough questions around why the rivers of Mumbai, officially known as nullahs (open drains), have been reduced to putrefying garbage and untreated sewage channels; and why in spite of piles of official reports and their recommendations for maintenance of Mumbai’s rivers, their condition continues to get worse. The answer lies in the state’s inaction and wrong actions that have systematically destroyed city’s natural watercourses, which not only protect Mumbai from floods, but are also an integral part of its urban ecosystem.

Rivers of Mumbai

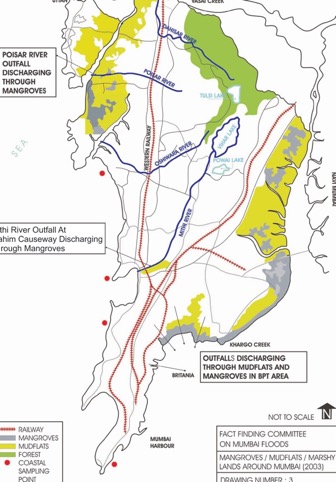

It took an extreme rainfall of 944 millimetre (mm) in 24 hours on July 26, 2005, leading to unprecedented floods and an official death toll of 456, for Mumbai’s administration and its people to realise the city had a river called Mithi, which, till then, was referred to as a nullah. Soon it was realised that Mumbai doesn’t have just one river, but three more rivers in its suburbs — Oshiwara, Dahisar and Poisar — that flow through congested informal settlements, commercial hubs, residential and industrial areas, and together form the natural drainage network of the city (see map 1: Rivers of Mumbai).

Mithi River originates from the overflow of Vihar Lake (built by the British sometime around 1860 to supply drinking water to the then Bombay) inside the Sanjay Gandhi National Park (SGNP) and also receives overflow from Powai Lake. It flows for about 17.9 kms before meeting the Arabian Sea at Mahim Creek and has the largest catchment area of 7,265 hectares (ha). The upper stretch of 11.8 kms of the river falls under the jurisdiction of the Municipal Corporation of Greater Mumbai (MCGM), whereas the remaining downstream portion of the river is under the administrative control of the Mumbai Metropolitan Region Development Authority (MMRDA). Mithi River forms the boundary between Mumbai’s island city and its suburbs.

Oshiwara River (also known as Walbhat River) starts from the Aarey Colony near SGNP, cuts through the Goregaon hills and after a journey of seven kilometres, finally empties into the Malad creek. Its total catchment area is 2,938 ha of which 53 percent is built-up with slums accounting for 23 percent share (data for 2005).

Mumbai’s third river, Dahisar, originates from Tulsi Lake inside the SGNP and flows across the northern suburbs and meets the sea at Manori Creek after travelling for 12 kms. Dahisar River’s total catchment area is 3,488 ha, of which 24 percent is built up (data for 2005).

Poisar (Poinsar) River also starts from SGNP and flows for about seven kms to end its journey at the Marve Creek. As of 2005, almost 53 percent of its catchment was already built-up. In the last 13 years since 2005, the built-up area in the catchments of these rivers must have gone up tremendously.

All these four rivers together form the natural stormwater drainage (SWD) system of Mumbai that carries excess rainwater (runoff) from various areas of the city, emptying it all into the creeks and the Arabian Sea. This drainage network is crucial for Mumbai as the city receives a heavy annual rainfall of over 2,400mm within the four months of June, July, August and September. Also, large parts of Mumbai are barely above the sea level (some even below sea level), thus prone to regular flooding.

Network of nullahs

Apart from these four rivers, Mumbai has a wide and intricate network of nullahs and drains that criss-cross the city like veins in the human body. As per MCGM’s inventory of stormwater drains, Mumbai has 261.52 kms of major nullahs that are more than 1.5 metres (m) in width. Minor nullahs, less than 1.5 m wide, run for 411.56 kms length. Arch drains are 601.80 km in length, whereas roadside drains are over 2,000 kms long. There are some closed drains, also known as dhapa drains, mostly in the island city, which are 549 kms in length. All these nullahs and drains empty into the creeks and the Arabian Sea through 174 outfalls.

These nullahs are important because they connect with the rivers of the Mumbai and act like their tributaries or distributaries. Almost each locality of Mumbai has a minor nullah crossing through it, which somewhere joins a major nullah that eventually meets one of the rivers. Thus, the health of Mumbai’s rivers depends on the health of its more than 3,800-km long network of nullahs and various types of drains.

But, over a period of time, the nullahs and rivers of Mumbai have been converted into open sewers infested with disease spreading vectors and preferred open spaces for dumping of solid waste.

Rivers or sewers?

As per the MCGM Act of 1888, the construction, maintenance and cleaning of city’s drainage system is the corporation’s duty. The corporation has to ensure that the city has two separate systems for stormwater drainage and sewage disposal. And, both must not mix up. But, in reality, Mumbai’s rivers are nothing but channels to carry untreated sewage to the creeks and the sea.

The length of Mumbai’s sewer lines is about 1,973 kms, but it does not cover informal and slum settlements where half of city’s population lives. Hence, untreated sewage, industrial effluents, etc from these areas flow into the local nullahs from where it enters the rivers and flows into the sea. It is estimated that almost 40 percent of the city’s untreated sewage flows into its rivers and nullahs. No wonder then at any point during the year, Mumbai’s rivers and nullahs are full of stinking sewage. Ideally, these rivers are supposed to carry only the run-off/stormwater and should be dry during rest of the months.

Encroachments restricting the river flow

Second major problem with the rivers of Mumbai, which, again has been promoted (or ignored) by the government authorities, is encroachments on and along the river paths. And, let us remember these encroachers are not slum-dwellers alone. Even planned developments, such as the Bandra-Kurla Complex (BKC) on Mithi, have come on the river lands.

A document of the MGCM notes that major cause of flooding of Mithi river is reclamation of the river by industrial units, diversion of the course of river for construction of Santa Cruz runway and taxi bay extensions, BKC reclamation, construction of walls around the Air India and Indian Airlines colonies, reclamation of natural ponds, etc. It also notes that “the main river has been forced to turn 90 degrees four times in rapid succession”. Flooding has also increased because of bunding of river with walls and embankments on both sides in some sections.

So, how does the civic agency deal with such encroachments and bunding of the Mithi river? It is widening and deepening the river, and also constructing concrete retaining wall of 21.588 kms length on both the sides of the river. Over 14.233 kms length of retaining walls is already done and the work is underway for the remaining free section of the river. This is sure to further destroy the river.

This frenzy of restricting the flow of rivers and turning them into drains is not limited to Mithi alone. The civic agency has gone ahead and ‘trained’ the other three rivers as well. For instance, the corporation proudly claims that ‘training’ and widening of 2,939 m of Dahisar River, 3,312 m of Poisar River and 2,118 m of Oshiwara River has been completed with RCC (roller-compacted concrete) at a cost of Rs 70.71 crore, Rs 200 crore, Rs 70.27 crore, respectively. Little does the government that promotes an anthem on Mumbai’s rivers understand the difference between a river and a drain. Rivers have a direct connection and relation with their floodplains and catchments. Creating concretised structures that severe them from their floodplains is a sure recipe to kill the rivers. Even residents living in close vicinity of these ‘trained’ rivers complain that post the construction of high cemented walls along the rivers’ courses, flooding in their area has increased, as excess run-off cannot flow into the nullahs and rivers.

Rivers as garbage dumpsites

Because the rivers of Mumbai have been neglected and systematically destroyed, they have become dumping grounds for solid waste by all and sundry. Last year in the month of April, volunteers of River March removed 1.47 lakh kg of garbage from a stretch of Poisar river. A 2016 report by the Environmental Policy and Research India (EPRI) had found that pollution levels in Poisar were 100 times more than the safe limit. Another study conducted last year by the Maharashtra Pollution Control Board (MPCB) found the water at the mouth of the Mithi river and Versova beach to be the dirtiest, with pollution levels almost 13 times above the safe limit.

Report after report but little action

Since at least 1975, committee after committee and report after report have made recommendations to the civic agency and the state government on improving the drainage system of Mumbai, including upkeep of its rivers and nullahs. But, even after decades, several of these recommendations remain unimplemented. An important comprehensive report known as BRIMSTOWAD (Brihan Mumbai Storm Water Drainage) was submitted to the MCGM in 1993. Among many other things, it recommended widening and desilting of the nullahs, including the four rivers, so as to increase their capacity of draining excess water during heavy rainfall days. The report noted that the existing capacity of nullahs — 25 mm per hour rainfall — was inadequate and the same should be upgraded to 50 mm per hour rainfall.

The BRIMSTOWAD report kept gathering dust till July 2005 when Mumbai faced unprecedented floods and the state machinery got into some action. However, it has been 25 years since the submission of the 1993 report, but its implementation (divided into two phases), is still not complete. As of last year, out of total 20 works listed under phase I, 16 are complete and four are under progress. Under phase II, a total of 38 works are listed, of which only 12 are complete, 23 are in progress and for three tenders are yet to be invited.

Post the July 2005 floods, another Fact Finding Committee (known as Chitale Committee) was appointed by the state government to find out the root causes of floods in the city and suggest remedial measures. The Chitale committee submitted its final report in March 2006, and more than a decade later, its recommendations, too, have not been implemented in totality.

Meanwhile, another consultant has been appointed by the MCGM to review and upgrade the 1993 BRIMSTOWAD report. The consultant is preparing an updated BRIMSTOWAD master plan for drainage in the city. Clearly, the state government hadn’t heard the old adage ‘a stitch in time saves nine’.

Climate change and floods

The ‘Maharashtra State Adaption Action Plan on Climate Change’, recently adopted by the state Cabinet, has a section dedicated to the vulnerability of Mumbai to urban flooding. It notes that “the Mumbai Metropolitan Region (MMR) area of 149 square km in 1971 increased to 1,000 square km by 2010. Its forest area declined from 1,045 square km to 879 square km over the same period. Similarly, area under industry increased from 45 square km to 140 square km, while agriculture area reduced from 2,098 square km to 1,381 square km.” The report goes on to say that “protecting forests around water catchment areas is no longer a luxury but a necessity”. However, in reality, the state government is opening the Aarey forests, which form the buffer of SGNP, to plunder. One of the four rivers to whom the recent River Anthem is dedicated — Oshiwara River — originates from Aarey Colony.

The state action plan on climate change has also carried out model-based assessment of flood possibilities in the city and found that “even after augmentation of the drainage capacity to 50 mm/hour, Mumbai’s low lying areas need special attention as these areas are exposed to the risk of high flood level and that flood risk mitigation practices should be implemented for the city”.

There is enough international scientific evidence as well to show that as climate changes and sea-levels rise, Mumbai is highly prone to the floods. A 2015 report by Climate Central, a US-based research organisation, has warned that as many as 11 million people are at risk in Mumbai alone if the global temperature rises by 4°C, which would lead to sea-level rise and submerge lands.

Another 2016 report, Global Environmental Outlook (GEO 6) of the UN, has said that nearly 40 million Indians will be at risk from rising sea levels by 2050, with people in Mumbai and Kolkata having the maximum exposure to coastal flooding in future due to rapid urbanisation and economic growth.

It isn’t without a reason that several developed countries have realised that ‘training’ rivers and diverting natural watercourses only adds to the flooding risks. Take the case of The Netherlands, which faced unprecedented floods in 1993 and 1995, leading to launching of a unique programme ‘Room for the River’ in 2007 that aims to restore the rivers’ natural floodplains, broaden the floodplains, restore marshy riverine landscapes to serve as ‘water storage sponges’, and provide biodiversity and aesthetic and recreational values.

Without taking any concrete action on the above mentioned problems faced by the rivers of Mumbai, just an anthem on the (dying) rivers of Mumbai cannot absolve the civic agency and the state government from its duty towards protection of the waterbodies and their catchments. An anthem on the rivers cannot hide the decades of neglect, apathy and wilful destruction of the city’s rivers. If you are serious about saving the four rivers, Mr Fadnavis, then ensure treatment of the very last drop of sewage and industrial effluent, stop ‘training’ the rivers, and create more space for these watercourses. Actions speak louder than words, or music videos.

Nidhi Jamwal (nidhijamwal@gmail.com) is an independent journalist based in Mumbai.

NOTE: Photos are of 2016.