Water sharing disputes across the country (and even beyond) are only going to escalate with increasing demands, and also with increasing pollution & losses reducing the available water. Climate change is likely to worsen the situation as monsoon patterns change, water demands going up with increasing temperatures, glaciers melt and sea levels rise. The government’s agenda of interlinking of rivers would further complicate the matters.

The ongoing Cauvery Water Dispute [iv] has once again brought the focus on interstate river water sharing disputes in India and what has been our experience so far. There is no solution of Cauvery water dispute in sight and the engineer-dominated Cauvery Management Board that the Cauvery Water Dispute Tribunal Award has recommended is unlikely to help matters.

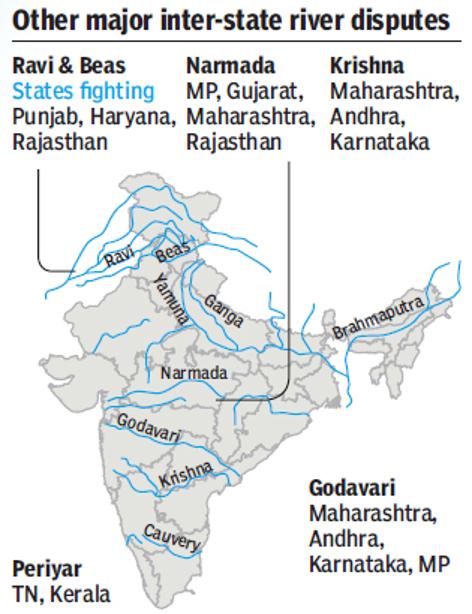

Current Tribunals Some of the water disputes that are ongoing now include the Mahadayi water dispute between Goa, Karnataka and Maharashtra, the Vansadhara Water Dispute between Odisha and Andhra Pradesh,the Krishna Water Dispute between Maharashtra, Karnataka, Telangana and Andhra Pradesh, Cauvery Water Dispute between Kerala, Karnataka, Tamil Nadu and Puduchery and Ravi Beas Tribunal Between Punjab, Haryana, Rajasthan and Himachal Pradesh. For all these five cases, the Tribunals set up under the Inter State Water Disputes Act of 1956 are still in office and supposed to be functioning, though in case of Cauvery and Ravi Beas disputes, there is no activity happening at the Tribunals. Even in case of Krishna dispute, the only issue the Tribunal is now discussing is the water sharing between newly created states of Telangana and Andhra Pradesh. So for example in the 2016-17 budget of Union Ministry of Water Resources, River Development & Ganga Rejuvenation (MoWR for short)[i], there is provision of Rs 0.68 Cr for Ravi Beas Tribunal, Rs 2.8 Cr for Cauvery Tribunal, Rs 2.6 Cr for Krishna Tribunal, Rs 4.52 Cr for Vansadhara Tribunal and Rs 3.1 Cr for the Mahadayi Tribunal.

Past Tribunals The Narmada Water Disputes Tribunal award came in 1979, the Godavari Krishna Disputes Tribunal award was announced in July 1980 and the Krishna Water Disputes Tribunal award was announced in Dec 2010. These tribunals no longer function. However, in case of the Krishna Water Disputes Tribunal, after the bifurcation of Andhra Pradesh and Telangana, the water distribution issue between these two states has been referred to it, so it is functioning again.

The Narmada Water Disputes Tribunal award did not entirely resolve the issue, the dispute between Gujarat and Madhya Pradesh lingered on many years after the Tribunal Further Award in 1979. Major project that the tribunal decided about, namely the Sardar Sarovar Project, is still incomplete, 37 years after the tribunal award and several petitions have been filed subsequently, since the Tribunal did not hear the affected people, who continue to struggle. Even people of dry region of Kutch, in whose name the project was justified, went to the Supreme Court, asking for greater share in Narmada waters. The Tribunal award is up for review in eight years, and the states are already gearing up for next round of fight.

In case of Godavari Tribunal decision, the Polavaram dam that was one of the key aspect of the decision, continues to be under construction and large number of disputes and litigations are still pending. The Krishna basin disputes has already seen need for second tribunal and its work is still ongoing.

All this shows that none of the tribunals have been able to resolve water sharing conflicts permanently.

The Indus treaty between India and Pakistan[iii] is often cited as an example of successful water sharing dispute resolution. However, the Indus Treaty basically divides the six rivers between the two states, giving absolute right to use waters of Beas, Ravi and Sutlej to India and most of the rights over waters of Chenab, Jhelum and Indus to Pakistan. The limited rights that upper basin areas of India have over the three western rivers, remains to be fully used, but many of the projects on these rivers have been challenged by Pakistan, and at least one of them was even taken to International Court of Justice at Hague.

There have been number of agreements between India and Nepal, including on Kosi, Gandak, Sharda and Mahakali rivers, but Nepal continues to have so much resentment that one cannot call any of them as successful examples of river water sharing.

Other ongoing Disputes In addition to the tribunals, the MoWR website lists three more disputes as ongoing disputes. The Polavaram (also known as Indirasagar) Dam in Andhra Pradesh has led to a dispute with Odisha and Chhattisgarh as the dam is going to submerge large parts of tribal areas of these states, but there has not even been an environment and social impact assessment, nor public consultation process. The Ministry of Environment and Forests have given a stop work order, but strangely, the order keeps getting suspended, and in the meantime, the Union Government has declared the project as a National Project and offered to fund it fully, though the project will be implemented by Andhra Pradesh. However, several petitions remain pending in the apex court against the project. Telangana has also raised a number of issues about the project, including share in benefits and backwater impacts. How is the project going ahead in spite of these issues, remains a mystery.

The second dispute that MoWR lists is about the Bhabali barrage on Godavari river. The MoWR website says about this dispute: “The State of Andhra Pradesh in May, 2005 brought to the notice of the Central Government that Government of Maharashtra was constructing Babhali barrage in the submergence area of Pochampad Project (Sriramsagar Project) in violation of the Godavari Water Dispute Tribunal (GWDT) award dated 7.07.1980. Babhali barrage is located on the main Godavari River in Nanded district; 7.0 km upstream of Maharashtra – Andhra Pradesh border. The Pochampad dam on Godavari River is 81 km downstream of Babhali barrage. Pochampad storage stretches to a distance of 32 km within Maharashtra territory and its submergence is contained within river banks in its territory under static conditions.” Following the creation of Telangana state on March 1, 2014, the dispute now is between Maharashtra and Telangana, but with signing of an agreement between these two states recently, this dispute may now be a history, though the MoWR website is yet to take cognizance of this.

The third ongoing dispute that MoWR lists is about Mulla Periyar Dam between Kerala and Tamil Nadu. The dispute here is basically about safety of an over 120 year-old dam, which if it beaches, will affect Kerala, when all the benefits are going to Tamil Nadu. Kerala, in rare magnanimity seen in interstate water disputes, has offered that Tamil Nadu will continue to get all the water it is currently gets, even though Tamil Nadu does not have much share it the basin, but the beneficiary state of Tamil Nadu is refusing to allow decommissioning of the dam. The dam will have to be decommissioned at some stage, sooner its safety issue is resolved, better it will be.

However, there are a number of other simmering issues. One major dispute that is soon likely to go the tribunal way is Mahanadi water sharing issue between Chhattisgarh and Odisha. Odisha government has already sent letters to the Centre, referring to the Inter State Water Disputes Act of 1956. The meetings of the Chief Secretaries and the Chief Ministers called by the Centre has not helped resolve the issue so far.

A dispute between Tamil Nadu, Karnataka and Andhra Pradesh on Palar River Water sharing has been brewing for some years. Another between Tamil Nadu and Kerala has started with Kerala seeking stage I environment clearance for Atapadi irrigation project on a tributary of Cauvery. The Sutlej Yamuna water sharing issue between Haryana and Punjab also keeps raisinging its head from time to time. There is also unresolved water sharing issue between Upper Yamuna Basin states. Between Maharashtra and Gujarat, the issue of water sharing of Tapi River remains unresolved now for some years, blocking the approval for Par Tapi Narmada and Damanganga Pinjal River Link proposals. However, none of these issues have so far gone the tribunal way.

Principles of water sharing The tribunals have been using a number of principles while deciding about water sharing between contending states. The Helsinki rules were issued in 1966, United Nations Convention on the Law of the Non-Navigational Uses of International Watercourses were finalized in 1997, the World Commission on Dams report came in Nov 2000, the Berlin Rules were issued in 2004. All of them have certain commonalities, but they differ in some aspects. This brief article will not allow detailed analysis of these rules and conventions, but we need to adopt and use them according to our situations. India’s National Water Policy and Draft National Water Framework Bill also mention some principles.

Environmental flows for rivers Earlier tribunal awards like the Narmada tribunal did not provide any water for the river downstream from the Sardar Sarovar Dam. It said that, since the downstream river was entirely in Gujarat, Gujarat can allocate water for the river from its own share. More recent awards like the Cauvery award of 2007 and the Krishna award of 2010 have provided some water, but the quantum is so small that it sounds more like tokenism.

So for example in the Cauvery award, there is a token provision of 10 TMC (thousand Million Cubic Feet), less than 1% of available flows or 740 TMC, for the river. But even for that provision there are absolutely no practical mechanisms to ensure the river gets it throughout its stretch. It seems to escape the attention of the tribunals that if there is no river, how will the states get their share of water?

In that context what the interim award dated July 17, 2016 of the Mahadayi Tribunal says is educative: “Rivers are important for many reasons. One of the most important things they do is to carry large quantity of water from the land to the ocean. There, seawater constantly evaporates. The resulting water vapour forms clouds. Clouds carry moisture over land and release it as precipitation. This freshwater, feeds rivers and smaller streams. The movement of water between land, ocean, and air is called the water cycle. The water cycle constantly replenishes Earth’s supply of freshwater which is essential for almost all living things. Except some few rivers, all rivers ultimately flow into the sea whether it is Arabian Sea or Bay of Bengal etc. Before merging into the sea the water of the river is available for consumptive and non-consumptive uses by the States concerned. Therefore, merging of water of river Mahadayi to the Arabian sea irrespective of uses, cannot be considered to be wastage of water. The plea of wastage of water may become relevant if surplus water is available. As indicated in the earlier part of this order, this tribunal has come to the conclusion that the State of Karnataka has failed to establish at this stage that the surplus was is available at the three points from which the water is sought to be transferred to Malaprabha basin if water available is 108.72 tmc at 75% dependability in the Mahadayi basin. For this reason, it is difficult for the Tribunal to accept the case of Karnataka that water goes into the sea is wastage.”

Implementation of Tribunal Awards Some of the tribunals have made provisions for implementation of the awards. So for example, the Narmada Tribunal Award made a provision of Narmada Control Authority, to which Rehabilitation and Environment Sub Groups were added. This arrangement has been useful to some extent due to provision of some independent members in the Environment Sub Group, though they are missing in other bodies. The Cauvery dispute lingers on over nine years after the Final Award of the Tribunal and on Sept 20, 2016, the Supreme Court has directed constitution of the Cauvery Management Board as provided in the Cauvery Water Disputes Tribunal Award. However, this engineers dominated body do not seem to have right constitution for river basin management in this 21st Century.

The government has been considering setting up of a permanent River Water Disputes Tribunal, but we need change in the interstate water disputes act to ensure that river, environment and communities get a voice in the functioning of the Tribunals.

In Conclusion It can be seen from the above facts that almost in every case, the dispute between states have arisen when a state goes for construction of major dam on interstate rivers. So there was no dispute on Narmada till Gujarat decided to build Sardar Sarovar Dam. There was no dispute on Mahadayi till Karnataka decided to build diversion structures under the Kalsa-Bhanduri Project[ii]. At the root of a number of disputes are dams like Polavaram, Mulla Periyar and Bhabali barrage. In Cauvery basin, the dispute started when the upstream state Karnataka proposed dams, threatening the water availability for irrigation systems in Cauvery delta.

Even if we look internationally, India shares at least 54 rivers with Bangladesh, but the dispute is there is only about Ganga River, after construction of Farakka barrage and regarding Teesta barrage after construction of another diversion barrage there. For rest of the rivers, there is no dispute so far.

If the plans of Inter Linking of Rivers get implemented, then the existing scenario is likely to undergo major change and the disputes are likely to multiply and would be much more complicated. A glimpse can be seen in Gujarat and Maharashtra where Par Tapi Narmada Link is still opposed by Maharashtra despite BJP Government in both states.

So the most successful way of sharing rivers is not to build large dams! In 21st Century water management scenario, we can avoid more disputes and complications by using the available water of our rivers in more prudent, sustainable and environment friendly way, without necessarily involving large dams and diversion structures or inter linking of rivers. But it seems we are going to learn only hard way!

In this context it should be mentioned here that, while the disputes and tribunals are about sharing of surface waters, India’s water lifeline today is groundwater. But strangely, the tribunals do not even include groundwater use while calculating and apportioning water use.

The biggest problem in the way the interstate water disputes have been handled by the central and state governments, the tribunals and the judiciary is that there is no place for the river, the people who depend directly on the river and those who get affected by the decisions of these bodies. Nor is there any role for environmental, social and cultural issues related to the rivers.

The legal and institutional architecture has no place for these stakeholders currently. We need to urgently change this.

Himanshu Thakkar (ht.sandrp@gmail.com), SANDRP

Note: An edited version of this has been published under the title “Interstate Water Issues: Disputes Aplenty” in Oct 14, 2016 issue of FRONTLINE magazine, see: http://www.frontline.in/cover-story/disputes-aplenty/article9153555.ece?homepage=true

END NOTES:

[i] http://wrmin.nic.in/writereaddata/DDG_2016-17.pdf

[ii] https://sandrp.wordpress.com/2016/08/02/mahadayi-water-disputes-tribunal-trouble-brewing-in-paradise/

[iii] For an article on Indus Treaty, see: https://sandrp.wordpress.com/2016/10/04/so-who-will-suffer-in-the-indus-water-imbroglio/

[iv] https://sandrp.wordpress.com/2016/09/23/cauvery-is-there-will-for-way-forward-will-constitution-of-cmb-help/

Recently a new wave of tussle and controversy over the Mahanadi water has come up between Odisha and Chhatisgarh. No solution in the share of water between these two states has been reached till date.

LikeLike

if there will be no dams , then from where will be hydro power be produced ? interlinking of rivers can solve water scarcity problems of millions of indians especially farmers . interlinking of rivers is not just the need of the century but need of the hour….ground water is scarce and cannot help solve the water crisis. every year kosi river destroys the lives of milions of bihari poor people because of its waters ..and the same time farmers of bundelkhand and vudharbha region are dying……interlinking of rivers is mandatory for a huge country like india .

LikeLike

All evidence shows that large dams or interlinking of rivers are not viable, desirable, least cost or democratic options.

LikeLike

Thank you very much for posting this

It is very very useful🌞

LikeLike

Our country has highly variable rain both in time and space. We have to store water in our house if the supply is erratic and use it whenever needed. Large dams have higher depth and hence low evaporation.If deconstruct severalamall dams in lieu of one big dam water will be lost during summer. Hence for feeding our population such large dams are very much needed.

LikeLike

Not really sir. The most benign, cost effective and quick storage option is groundwater. Our aquifers are empty. Similarly our soils. Increase carbon content to increase its; ;capacity to store water. Thirdly, local water storages, since rain is decentralised and demands are decentralised. Lastly, use existing storage capacity optimally. Try and reduce siltation. Desilt local systems. If we do all this,FIRST, we may have done a lot. We wont need big dams.

LikeLike

I really think the writer did a commnedable job in approaching all of the aspects also I totally agree with the conclusion he made.

Was an interesting read to such a mind boggling topic.

LikeLike

Many thanks, for your feedback and kind words. Much appreciated.

LikeLike

Sir, you have done a great job

LikeLike