By Anil Prakash

Rivers are not simply rivers, but they are our cultural life lines. Freshwater of rivers, fertile land on either side and island inside them, living beings, plants and vegetation and millions and millions of human beings, laughing and singing and shedding tears of sorrow, all taking together constitute the world of rivers. Men tried to fetter these rivers and construct dams, hydropower projects, riverfronts, embankments and barrages over them, encroached the floodplains, all in the name of progress. But the rivers want to break these fetters, as if they are giving a message to mankind to break the fetters of slavery, and to live a free and natural life. Whenever obstructions are put to them or they are polluted, they break their self restraint.

GOOGLE IMAGE OF FARAKKA BARRAGE

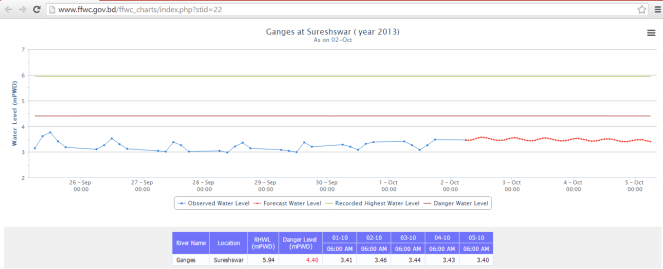

The 2245 m long Farakka Barrage is one of the most debated river management projects though for reasons which have nothing to do with either environmental or demographic reasons. Built primarily to serve the twin purpose of regulating the amount of Ganga water to flow out from the Indian territory into Bangladesh (East Pakistan then); and to ensure that sufficient water is diverted to Hooghly river to enable the regular flushing of silt at Calcutta port, the Farakka Barrage has been more often mired in controversy as India and Bangladesh have disagreed over the share of Ganga water between the two countries. While in the recent past, some efforts have been made to resolve this contentious dispute between the two nations, no thought has been spared so far on the long term impact the barrage has already caused and continues to do on an ongoing basis.

Though the Farakka Barrage was commissioned in 1975, work on the project had been going on for long. The structure of the Barrage was completed as early as in 1971 but the feeder canal which diverts water to the Bhagirathi river (as the Hooghly is called at this point) was completed only in 1975. By this time however, the cost of the project had escalated and when it was finally completed, the Farakka Barrage cost the nation Rs. 156.49 crore. The cruel irony is that since its commissioning, the Farakka Barrage has cost the nation much more but leave alone calculating the total cost, barring a handful, no one is even willing to concede the fact that the Barrage has caused irreversible harm to environment and society. The Barrage is being maintained by the Farakka Barrage Project (with 878 employees[1]), under Union Ministry of Water Resources, with jurisdiction upto 40 km upstream of the barrage, 80 km downstream along the right bank feeder canal and in the downstream area upto Jangipur barrage[2].

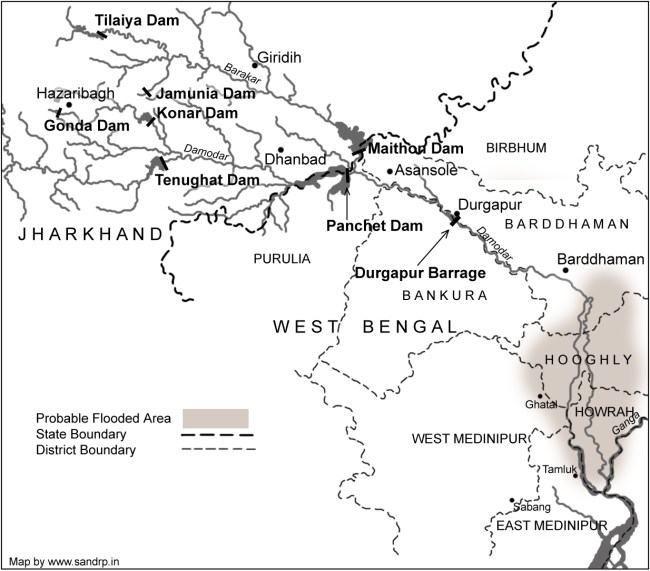

The Farakka Barrage was modelled on the lines of the Damodar Valley Corporation (DVC)- one of the first major riverine projects undertaken by the Central government under the influence of Nehruvian model. Both the DVC and the Bhakra project in the northern India were reflective of the government’s viewpoint that river management projects in India needed to be modelled on western lines – with its emphasis on large dams. In fact, plans for the DVC had already been drawn up by the British before independence during Lord Wavell’s tenure as Governor General. The entire project was modelled on the lines of the Tennessee Valley Authority of America and its chief engineer was actually appointed by the government of Independent India as the Chief Administrator of the DVC. When the DVC was planned and work on it was initiated in the late 1940s & early 1950s, the government was lavish on its claims regarding the benefits from the project. For eastern India, the DVC was considered to be a panacea to several problems in areas of power, irrigation and flood control. But as experience later showed, the claims had been falsely made on all fronts: the DVC in fact, made more areas in West Bengal prone to flood than before; the project’s utility in irrigation & power generation programmes was minimal.

Faulty Projections

By the late 1950s evidence was mounting that the projections made by the planners of the DVC had got it all wrong. The greatest demerit in the DVC was the sharp decline in the discharge capacity of Damodar river: from a level of 50,000 cusecs in 1954, the figure touched abysmal level of 20,000 cusecs. By 1959, the depth of Calcutta port had declined considerably after the construction of the Maithon and Panchet dams. The discharge capacity of several other rivers in the region like Jalonshi, Churni, Mayurakshi, Ajai and Roopnarayan also declined greatly and further contributed to the rising bed of the Hooghly. The situation slowly started reaching the point of no return and by the late 1950s, large ships stopped coming to Calcutta port and instead opted for Diamond Harbour.

SANDRP MAP OF DAMODAR VALLEY DAMS

These facts were not hidden from the policy makers and planners when work on the Farakka Barrage was initiated. Yet, they chose to remain myopic and contended that the Barrage would flush out silt and mud from the Hooghly and thereby it would be possible to reclaim Calcutta port. What was ignored was the fact that till the DVC project had been initiated, the problem of Hooghly not getting desilted had never risen because of the nature and timing and force of the floods in the Damodar and Roopnarayan rivers. But, once various dams came up in the course of the DVC, these rivers lost their capacity to flush the Hooghly thereby jeopardising Calcutta port.

The Farraka Barrage was thus intended to correct a un-envisaged adverse impacts created by DVC dams. However, as events have proved, the step taken to correct a previous wrong move also turned out to be a faulty and unwise decision. However, it is not that words of caution were not available when the DVC dams or the Farakka Barrage were initially planned: they were only not heeded. To illustrate, Kapil Bhattacharya, an engineer in West Bengal contended that the amount of water that could be diverted from the Farakka Barrage into the Bhagirathi, would not be sufficient to flush the Hooghly to the level that Calcutta could once again be used as a port. He also suggested that the DVC should be modified in a manner so that water from river Roopnarayan flows into the Hooghly which would ensure regular flushing of the river. Regarding the Farakka Barrage, Bhattacharya further said that the project would reduce the water carrying capacity of the Hooghly and thereby make more areas in West Bengal prone to floods. He had further cautioned that there would be heavy silt accumulation even in river Padma on the Bangladesh side of the border and this would further make areas on the right bank of Padma flood prone.

Creating Problems at both Upstream and Downstream

An alarming development has been the steady decline of the Ganga’s depth. In 1975, when the barrage was commissioned, the depth of the river at the barrage was 75 feet. In March 1997 when I visited the area with some friends, we were shocked to find that the depth of the river was only 13 feet. In effect, this means that the bed of Ganga had risen by 62 feet in the past years. Latest report shows that Ganga has become a havoc and the erosion goes on increasing year after year at Malda and Murshidabad districts.

Actually the Ganga river system transports vast amount of fluvial sediment. The Ganga used to be desalted up to 150 feet during flood season every year. On construction of Farakka barrage natural flushing of the sediment has been obstructed.

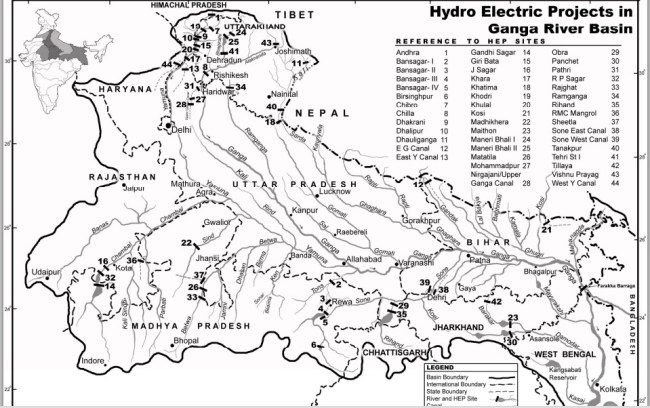

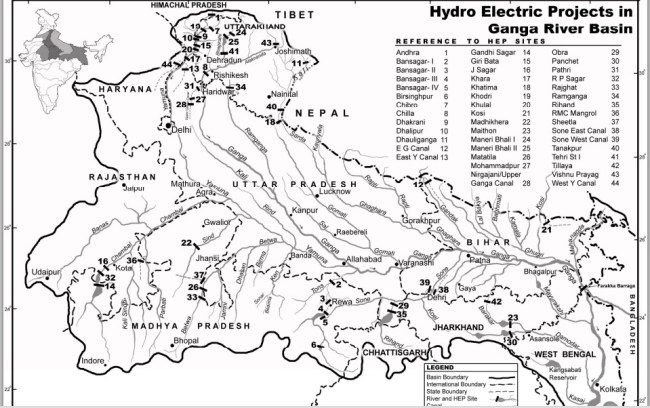

Ganga Basin Map (source: https://sandrp.in/basin_maps/)

This alarming development has led to untold misery to the people of Gangetic region of West Bangal, Bihar and Eastern UP as the level of the bed of all tributaries of Ganga has risen steadily. As a result, thousands of Chaurs (lowlands) that previously used to remain flooded only during the monsoons, now remain submerged under water for as long as ten months. The problem of constant water logging not only leads to possibilities of the outbreak of infectious diseases, but also causes unfathomed economic and social miseries on the people in these regions. Nature of the soil becomes alkaline and already lakhs of acres of once fertile land in Bihar have now turned totally barren. The fertility of the Gangetic plains today is a poor image of yesteryears.

While the problem of submergence as a result of the Farakka Barrage is acutely felt upstream of the barrage, the problem is one of erosion downstream of the barrage. As the water discharged into the Bhagirathi and the Padma is devoid of any silt, the water tends to cut into the land more sharply than in the past. As a result the problem of soil erosion is being very acutely felt in villages and towns on the banks of the Bhagirathi.

Depletion of Fish Resources

Besides water depletion, river diversion and dam projects also wreak havoc among the fish living in these waters. These projects adversely affect the fisheries which are migratory in nature. Dams and barrages act as barriers in their migratory paths and several species have either already become extinct or are facing extinction as they breed in a particular type of water while inhabiting in a different sort. The Farakka barrage has over the years acted as a barrier to the migration of marine & deltaic fish leading to the near absence of several popular varieties in the entire northern India. As the waters of several rivers of northern states directly or indirectly flow into the Ganga, there is a similarity in the type of fish found in the rivers. There are many aquatic verities (for instance prawn) that inhabit in fresh water but breed in marine water. Likewise, there are other species – like Hilsa – that inhabit in marine water, but have migrated upstream to breed. The Ganga once used to have plenty of Hilsa but this has changed as the fish is no longer able to breed leading to the near extinction of the Hilsa in the Ganga upstream of the Farakka Barrage.

In fact, it is not just a question of Hilsa alone, but there has been a substantial drop in the fish population on the entire Ganga. Prior to the barrage, during monsoon, there used to be a very high population of eggs and spawns in this stretch (UP and Bihar upstream of Farakka) of Ganga. After catering to the local needs (there is great demand for fish in Bihar and eastern UP) a substantial amount of eggs, prawns and different varieties of fishes used to be sent to other states. Today barely about 25 per cent of the local demand is met by the fish caught in this stretch and for the rest; the people have to depend on fish caught in other states.

It has been estimated that there has been an overall decline of 80 per cent in the entire population of fish upstream of the Farakka Barrage. Large fish, once found in abundance in the Ganga and its tributaries are no longer available and millions of traditional fishermen who have made their living for generations by catching fish now face destitution. What had previously been a close relationship between the fishermen and local customers have now been replaced by a cold system comprising air-conditioned trucks and ice-laden crates of fish brought in by large companies from other states like Andhra Pradesh. This not only makes the fish beyond the reach of the poor, but also alienates traditional fishermen from their ancestral profession in a situation where they do not have the training to do other jobs.

The Farakka Barrage has adversely affected the ecology and economy of Bangladesh too. Before 1975 Ganga used to flush out the Padma basin in Bangladesh and spread the alluvial soil in agricultural fields. But the barrage has disrupted this natural process. Now tides of the sea fill sand in the bed of Padma and also fields around it. Lakes and ponds are filled with saline water. The ground water level has fallen down resulting in drying up the shallow tube wells and dug wells. The Barrage has caused serious damage to land and populace both upstream and downstream of the barrage. Corrective measures are called for immediately and if not taken then there are portents of much greater havoc both to the people and to the land.

Chain of barrages will worsen the situation

The new plan of union government[3] to built chain of barrages along Ganga, every 50-100 KM will further worsen the situation. Natural process of silt transport and distribution in flood plains will be completely obstructed and breeding of migratory fishes will be further disturbed. The government should review this plan. A high level inter-disciplinary team need to be appointed to study at length the problems that have surfaced on account of the Farakka barrage and suggest measures that can be initiated to reverse the process of the damage. This plan will not succeed in either making Ganga Navigable or help the cause of rejuvenation of Ganga that the new government claims it is committed to. Strangely, the plan was announced without any details, public participation, environmental impact assessment, social impact assessment, public participation or participatory decision making. Free flow of Ganga is essential for rejuvenation of this holy river.

Ganga Mukti Andolan

Since 1982 fisher-folk and peasants of gangetic region are contending that rivering projects like dams, barrages and embankments are leading to economic downfall on account of fish depletion, submergence and fertile tracts turning alkaline. The Ganga Mukti Andolan has its origins in the resistance to the system of ‘Panidari’in Bihar. Under this system, waterlords and power contractors had fishing rights of Ganga and its tributaries. After a long struggle zamindari (Panidari) and contract system was abolished in January 1991 and traditional fisher people were given free fishing rights in 500 KM stretch of Ganga and in all rivers passing through the Bihar state. The movement continuously raised the issue of pollution caused by factories and thermal power station. Ganga Mukti Andolan has thus, moved from a movement of social and economic equity to one that questions the very model of development that is destroying the Ganga and those who depend on it. The movement wants a new direction for river management.

(Contact address of author: Anil Prakash, Jayaprabha Nagar, Majhaulia Road, Muzaffarpur – 842001, Bihar. Mobile – 09304549662, email – anilprakashganga@gmail.com)

END NOTES:

[1]Annual Report of Ministry of Water Resources, 2011-12

[2] http://mowr.gov.in/forms/list.aspx?lid=252

[3]PIB press release of Ministry of Water Resources on June 6, 2014

Farakka has profoundly changed the character, sediment regime and flow of Ganga. It is affecting lives of lakhs of people in India and Bangladesh through cycles of erosion, sedimentation, floods and affected fishing. Our response to the issue has been dismal. We have not conducted a single review of costs, benefits and impacts of Farakka Project so far. In addition to Farakka , Lower Ganga (Narora), Middle Ganga, Upper Ganga Barrages (Bhimgoda), Kanpur Barrage, Hydropower projects in Uttarakhand and other upstream states have affected the river in most profound ways. If we want to rejuvenate the Ganga, we need to institute a credible independent review the existing Barrages, not plan new ones. May be we can begin with a demand for such a review for Farakka on urgent basis. One World Rivers Day, let us wish for a long and healthy flow for the Ganga River, a symbol of all flowing rivers in India!

Farakka has profoundly changed the character, sediment regime and flow of Ganga. It is affecting lives of lakhs of people in India and Bangladesh through cycles of erosion, sedimentation, floods and affected fishing. Our response to the issue has been dismal. We have not conducted a single review of costs, benefits and impacts of Farakka Project so far. In addition to Farakka , Lower Ganga (Narora), Middle Ganga, Upper Ganga Barrages (Bhimgoda), Kanpur Barrage, Hydropower projects in Uttarakhand and other upstream states have affected the river in most profound ways. If we want to rejuvenate the Ganga, we need to institute a credible independent review the existing Barrages, not plan new ones. May be we can begin with a demand for such a review for Farakka on urgent basis. One World Rivers Day, let us wish for a long and healthy flow for the Ganga River, a symbol of all flowing rivers in India!

Conflicts in South Asia: Rising tension and Policy options across the sub-continent

Conflicts in South Asia: Rising tension and Policy options across the sub-continent