Guest article by Anantaa Ghosh

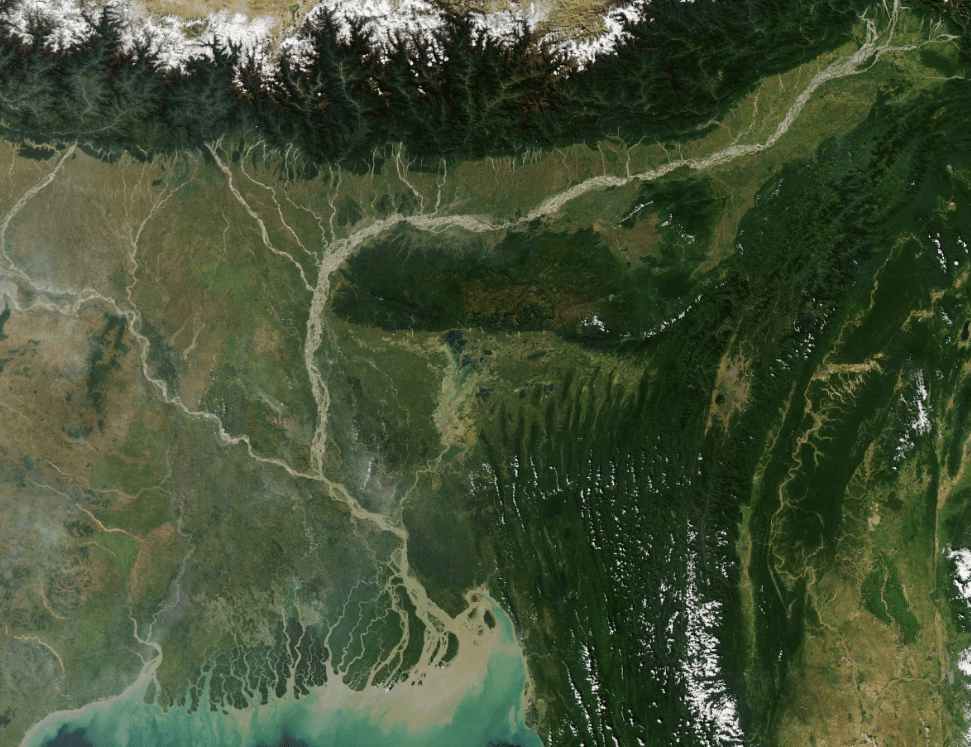

[Feature image above: A NASA Earth Observatory image by Lauren Dauphin]

Author’s note: In this article, I have taken grammatical liberties by omitting the use of ‘the’ before a river’s name and ‘it’ when referring to them. I firmly believe that reimagining and re-understanding rivers necessitate a profound change that extends to our lexicon as well. Consequently, I am deliberately employing the pronoun ‘they’ to refer to Brahmaputra and all the rivers mentioned herein, rather than ‘it’ which may reduce the river to an object. I also refrain from using ‘he’ or ‘she’ (as per Indian mythology) as these pronouns tend to impose a mythological identity as the sole identity of a river,, negating the multifaceted nature and diverse forms of identity that a river has.

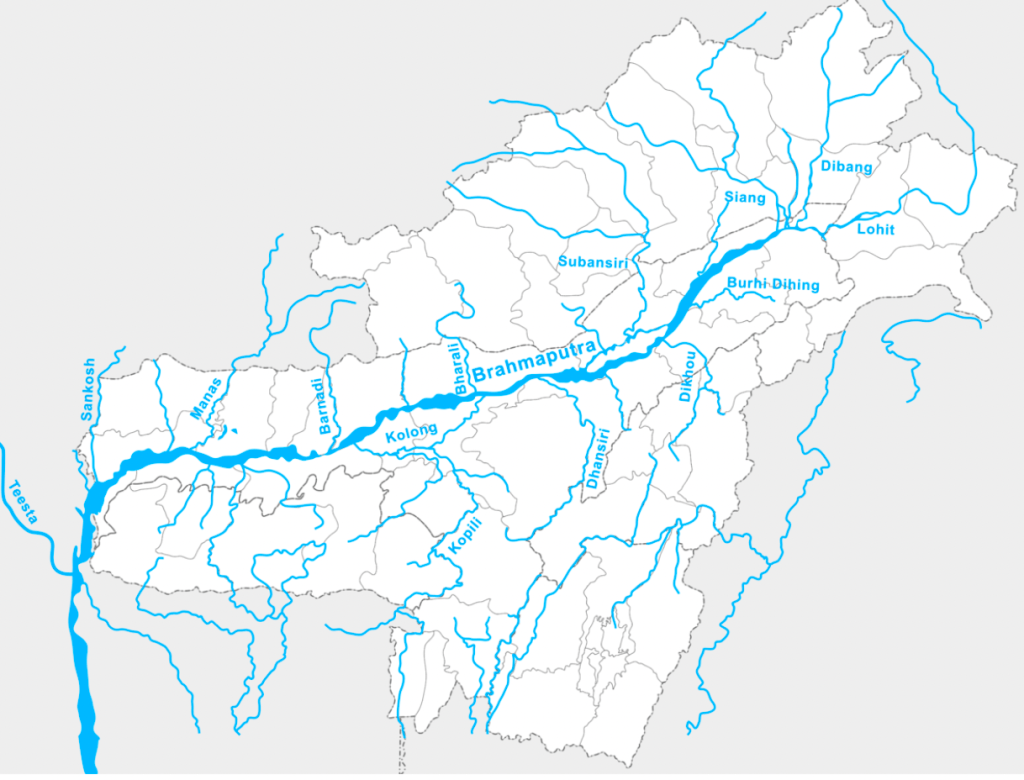

Brahmaputra, the braided Himalayan river, descends from the Mansarovar region and is known by many names like Yarlung Tsangpo, Siang, Dihang, Luit, and Jamuna. Theyhave protected, nourished and taken care of the people who have always shared a personal connection with them. The river acted as a natural barrier against Mughal invasions during the 17th century. All those who ruled the land realized early that knowing the river would help strengthen their empire. In spite of this, the river has never found a proper place in human-centric history and has significantly been pushed to the margins. It is only in the folklore, myths and songs of their people that Brahmaputra has always found a place. They have forever chronicled and sung of their river’s beauty and fury, kindness and power.

When studying the history of tea plantations in Assam, one will find a lot of material on the discovery of tea, the change of the indigenous Assam plant into a hybrid shrub, the labor transportation and of course the iron steamers due to which the plantations prospered and became a huge success. But what of the river? Brahmaputra, which played the most crucial role in the growth of the tea industry, and over time bore the greatest burden for it, hardly finds a mention in these historical records. So, let’s try to re-read the history by making the river the center of the narrative; like ‘amphibians’, as Arupjyoti Saikia says, instead of being too rooted on land and behind embankments[i].

Before delving deep into the tea plantations, it is worth discussing the pre-colonial agrarian activities, commerce and transportation which had thrived in Assam because of the dense network of rivers. The early Ahom rulers who were from Mong Mao (currently the Yunnan province), were already skilled in wet rice cultivation and chose the floodplains for better irrigation. They preferred smaller river valleys that had a lot of silt deposited by the rivers and within a short period of time, wet rice cultivation was thriving due to Brahmaputra and their tributaries. While building embankments for flood control during the next two centuries, the Ahom rulers also made sure to use the river for other purposes like trading goods. They ensured that ‘chawkeys’ are set up on river banks for inter-regional trade and collection of taxes from such trade. “These ‘chawkeys’ also served as places where occasional haats (periodic markets of exchange (barter) in South Asia) were set up”[ii]. Transportation of goods using the vast network of rivers was much easier which helped such a setup. The clash between the Ahom rulers and those in Bengal subsided once trade relations began and this was wholly dependent on the river.

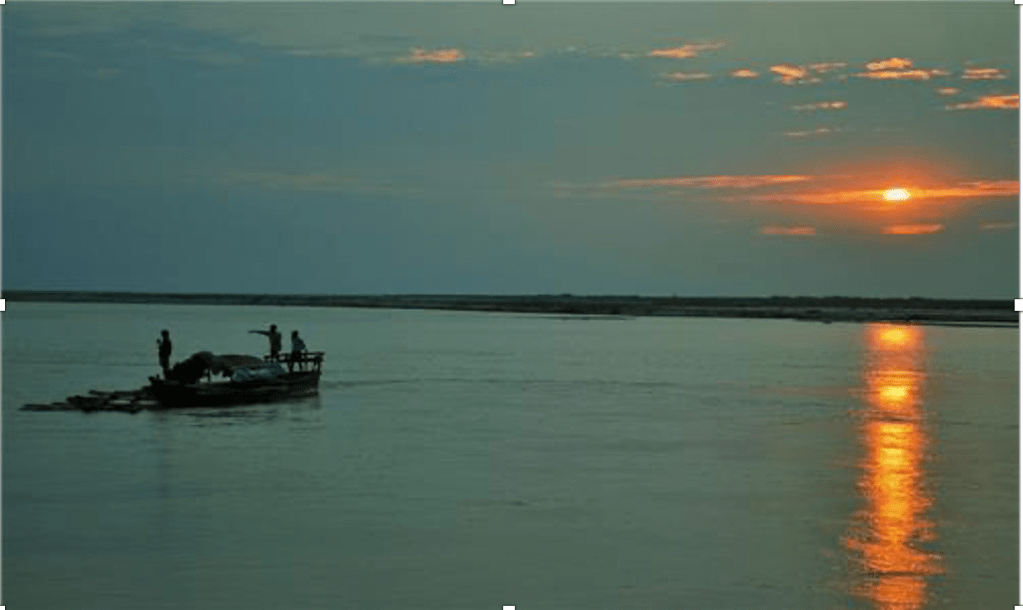

Boats have been a recurrent motif in Assamese literature and it only proves the connection that the people have shared with Brahmaputra. Boatmaking was a craft and an industry that flourished before the railways. People would travel short distances using small boats which would be made from the trunk of hollowed trees, the structures of which were vastly different from the ones used in Ganga. Navigation was a huge task considering the number of sandbars present in the riverbed.

The people were used to the annual rhythms of flood and recession of Brahmaputra. In spite of the embankments, they would avoid staying on the heavily flooded banks and would constantly shift. When there was heavy damage, the rulers would shift even their capital.

Even back then Brahmaputra wasn’t untouched by the powers of the state. The rulers would tax the boatsmen and frequent disputes took place over the water passageways[i]. Even going back to the time before the Ahoms had invaded (before 1200 CE), control of Brahmaputra and their tributaries was essential to gain control of the valley.

Tea Plantations

The river became the central focus once again when the East India Company gained control of Assam in 1826. Robert Bruce, a Scottish naval soldier was the first to discover tea plants in the hills of the northeast. The word discovery isn’t appropriate, though, for he merely found them. The Singpho people were already in the habit of consuming a concoction of dried leaves[iii]. He informed his brother Charles Bruce about it who then found the indigenous plants growing on river banks. But the wild tea plants had to be ‘domesticated’ first so that they could give higher yields, which meant shortening the plants and increasing the girth.

In the year 1834, a scientific expedition was led by surgeon-botanist William Griffith in Assam to confirm the presence of tea plants. He and his colleagues traveled from Calcutta to Cachar to climb the Khasi hills. To make an upward journey to Eastern Assam from there, they descended to Brahmaputra at Guwahati. It is said that the overall journey, by boat and road, took them four and a half months. Finally, the first batch of tea was ready and was dispatched for sale from Assam to London on 8 May 1838. It was sold on 10 January 1839 in London, where it received an enthusiastic response[i].

The location for tea cultivation had a broader impact on the ecology. The planters of Assam experimented with various forms of soil, the first experiment being conducted on a char (a tract of land in the middle of the river)at the confluence of Brahmaputra and Kundil in 1835 but the experiment failed[i]. Towards the end of the 19th century, after a lot of experience, the planters agreed that newly cleared forest lands with virgin soil tend to give more yield, though after some decades the production tends to fall.

Assam’s complex geography of linked landscapes was thus delinked and redesigned by the planters for their greed for commercial gain. To them, the ‘landscape’ seemed very untidy and needed to be shaped for better usage. The tea plantations which they grew stood at the foothills disrupting the linkage between the river, the hills and the plains[i]. The planters preferred hillslopes more than grassland not just because of the yield but mostly because they were afraid of floods. The planters, all of them being Europeans had little to no idea about South Asian rivers and ecology and hence, they could not imagine what it’s like to live in harmony with rivers. They feared the rivers and felt a constant need to gain control over them. The damage that they were causing by changing the nature of the environment was far beyond understanding. They employed Nagas to clear the forests. With such a massive level of tree felling, the river’s ecosystem got affected along with the soil which lost its ability to get replenished. Inadequate drainage systems were causing further imbalances. The combination of all these factors led to a new pattern of soil erosion in the hills which not only caused several planters to abandon their previous plantations but also increased the annual sedimentation in rivers. Studies in Malaysia have proved how tea cultivation has increased soil erosion thus, increasing the overall sediment in rivers. If such a study is conducted here, then we might obtain similar results.

One of the most important roles that Brahmaputra played was in the transportation of labor and tea chests. A British newspaper named Blackburn Standard wrote, “The distance of the tea districts from Calcutta, though great, can be but little obstacle when such a noble river as the Brahmaputra is open at all seasons for boats of largest burdens, even to the foot of the hills where the tea grows.”[iv] Yes, a noble river indeed who is kind enough just to ‘give’ and not ask for much in return!

As previously stated, boats were the most convenient mode of transportation. The problem with roads was that they were not well constructed yet and most were subject to frequent flooding during monsoons. Railways too did not develop until the early 1900s. Most of the people who were employed to work in the tea plantations were ‘coolies’ from the Chotanagpur plateau and other famine-stricken areas of eastern and central parts of India. The ‘coolies’ were transported in the same way as their Mauritian counterparts, like commodities. They were crammed into the lower decks of steamers which were then being used to transport laborers as quickly as possible to the plantations. The journey took at least 5 days and usually much longer than that. Hygiene was neglected and so was the food. If any worker died during travel they were thrown off the steamer into Brahmaputra who then carried the unwanted deceased like their own.

The workers were brought to Calcutta mostly by rail after which they were made to wait for medical examination. Once it was over, they were made to board large commercial steamers. Some were taken via country boats too, (it was mostly for those who needed to go to Sylhet and Cachar) which could only hold 20 passengers. The steamers on the other hand could hold 200-300 passengers. In 1875, Dhubri, situated on Brahmaputra was turned into an emigre port for embarkation.

The making of the steamers is another interesting story for the steamers which plowed on Ganga were different from the ones which were used along Brahmaputra. Also, the steamers and the country boats carried the tea chests thus, making tea an economic success for the East India Company. But that’s a story that we will keep for the second part of this article.

All those who have ruled the land adjoining Brahmaputra and their tributaries have thought about how they can utilize them for their gain, be it political or economic. But the amount of ecological damage that Brahmaputra incurred was way more in the time of the Company’s rule. The Company laid the seed for typical Western utilitarian thought of how a river, like land, is a property that, to date, we are nurturing. The key difference lies only in terms of ownership. While land can be possessed by individuals, rivers are considered to be the property of the state, ready to be used as per the state’s requirement.

But what happened to living in peace and harmony with the rivers, understanding and adjusting to their annual flows and recesses? Rivers, like us, are bodies susceptible to change. As our thinking increasingly embraced utilitarianism and an unwavering focus on human interests, the river underwent a profound transformation, largely due to our own interventions and their consequences. We have recorded the changes that were taking place amongst us, the humans and the places where we live or the things that we have built, but forgot to record the changing environment around us. Hence, the same rivers who have nourished our ancestors now seem so unkind, violent and a complete stranger to us.

Anantaa Ghosh (22anantaa01@gmail.com)

References:

[i] Arupjyoti Saikia, The Unquiet River, 2019.

[ii] Nabanita Sharma, Market Formation in Assam: Nature of Trade in and around the Brahmaputra Valley, C. 1826–1905

[iii] H.A Antrobus, A History of the Assam Company, 1957.

[iv] Blackburn Standard, Wednesday, 15 August 1838 (collected from The Unquiet River).