–J. Mark Baker (JMark.Baker@humboldt.edu), Humboldt State University, Arcata, CA, USA

Introduction

This article is part one of a two part summary of the results of a study on the socio-ecological impacts of privatized, small, run-of-the-river hydropower projects in Himachal Pradesh.[1] It is based on field research conducted in 2012 on all 49 commissioned small hydropower projects in the state.

In the late 1990s Himachal Pradesh, as did other states in this region, launched a series of initiatives to privatize and promote small hydropower production (Sinclair 2003). In 2006 these initiatives were incorporated into a new hydropower policy that aimed to generate revenue through the sale of surplus power to neighboring states and to promote the state’s own development (GoHP 2006). Because the levels of investment necessary to develop hydropower exceed the state’s financial resources as claimed by the policy, Himachal Pradesh’s power policy provides for private sector involvement and uses central government subsidies. Small hydropower project construction and operation in Himachal Pradesh is entirely privatized (GoHP 2006). Small hydropower projects mostly utilize run-of-the-river power generation technologies to convert hydropower into electricity; this study uses the Himachal Pradesh government definition of small as 5MW or less (though the Government of India defines small as below 25 MW capacity).[2] By 2012, only six years after the implementation of the policy, there were a total of 49 small hydropower projects generating electricity in the state (including the approximately 8 projects commissioned before 2006) (map 1). Additionally, approximately 50 more projects were under construction, and approximately 400 were in various stages of planning and approval (GoHP 2012) (map 2).[3]

The state established a nodal agency, Himurja, to oversee the private development of the state’s small hydropower potential, and to promote utilization of renewable energy more generally. In 2006 the state formalized the processes and mechanisms that govern private sector involvement in electricity production by passing the Hydropower Policy. Himurja plays a central role in this process by allocating government-identified small hydropower project sites to private corporations. After receiving an allotted project site, the corporation (referred to as the project developer or independent power producer) must prepare a series of detailed project reports that include, for example, two years of streamflow data and analysis of the engineering, economic, hydrological, geological, and environmental characteristics of the project. Once Himurja officers approve these reports, they and the project developer sign a Memorandum of Understanding, a Techno-Economic Clearance document and eventually an Implementation Agreement. At that point the developer begins the work of securing the required No Objection Certificates (NOCs) from the relevant state and local government entities including the Wildlife Department, Forest Department, Irrigation and Public Health Department Fisheries Department, Public Works Department, Pollution Control Board, Revenue Department, and affected Panchayats. After obtaining the required certificates, the power producer may commence project construction.

Construction costs generally range from Rs 6-8 crores per megawatt, but these are quickly recouped through the sale of electricity to the Himachal Pradesh State Electricity Board. Once the project is commissioned, the HP State Electricity Board guarantees the independent power producer a purchase price of Rs 2.50 per kilowatt hour – the equivalent of approximately Rs 2.2 crores per megawatt per year.[4] The project reverts to the state government free of cost after 40 years of operation. The developer pays the state government no power royalties for the first 12 years of the project’s life. However, for the next 18 years the developer must provide 12% of the power it produces free of charge to the state; for the remaining 10 years it must provide 18% free electricity to the state.

For small hydropower projects, there is no requirement that the project developer prepare a formal environmental and social impact assessment or environmental and social management plan subject to public review. Nor is the developer required to hold public hearings about the proposed project. This is a serious issue because the absence of a formal environmental assessment and hearing process prevents members of project-affected communities and other civil society groups from sharing concerns about the projects’ anticipated effects. This is one of the reasons for the growing and significant level of local opposition to small hydropower development in the state. A significant amount of the local opposition to small hydropower projects stems from the ways in which such projects disrupt rural livelihoods, combined with the inadequacy of local benefits such as rural employment generation and other forms of direct compensation. The next sections describe some of the livelihood disruptions the commissioned small hydropower projects have caused. The discussion is organized district by district, reflecting the geographical pattern of these disruptions.

District Kangra – disruption to local irrigation systems and farmer collective action

The majority of District Kangra lies on the southern side of the Dhaula Dhar mountain range, from where it extends across Kangra Valley and into the Sivalik Hills. The district is notable for its extensive network of community-managed gravity flow irrigation systems (kuhls). In Kangra Valley alone 750 large and more than 2100 small kuhls irrigate approximately 40000 hectares (Baker 2005) (figure 1).[5] Kuhl irrigation water is crucial for both kharif crops (rice and corn) and rabi crops (wheat and potatoes). These crops, except for potatoes, are almost entirely used for home consumption. Historically, kuhl irrigation water was essential for driving water-powered mills (gharats) and other machines, as well as irrigating home gardens, watering livestock, and meeting household needs for non-potable water. The importance of ensuring the continuity of these kuhl irrigation systems is reflected in the language of the No Objection Certificates that project developers must obtain from the Irrigation and Public Health Department as well as from village panchayat pradhans. These certificates contain language that protects community-managed kuhls from disruptions by small hydropower projects and requires the developer to pay full compensation if a project damages or disrupts a community-managed kuhl.

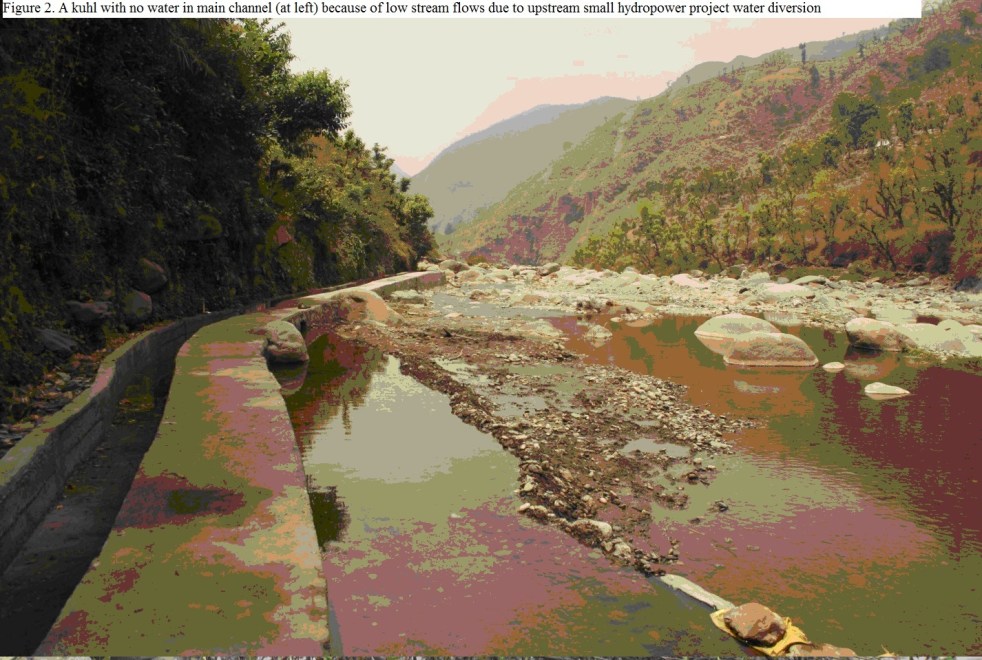

Despite the protections delineated in the No Objection Certificates, small hydropower projects commonly disrupt kuhl irrigation systems or cause them to cease functioning altogether, either by physically damaging the irrigation system or by diverting the water on which the irrigation system relies (figure 2). When a kuhl is damaged or deprived of water, farmers must shift to rainfed cultivation. Output from rainfed crops is invariably much less than for irrigated crops, in part due to unpredictable rainfall, increased vulnerability to drought, and damage from hailstorms at harvest time. Throughout the state, small hydropower projects have disabled a total of at least 13 kuhl irrigation systems; in none of these cases did the project developer compensate farmers for their losses. This level of disturbance to irrigation is significant – for example, one of the disabled kuhls was the primary source of irrigation water for approximately 2000 households.

Not all local farmers have not stood by idly, watching the lifeline of their subsistence agricultural economy go dry. Our research documented countless visits from village representatives to district administrative authorities petitioning them to intercede on their behalf in order to seek redress, compensation, and/or release of adequate water flows necessary for irrigation. Despite these frequent and often repeated requests, we did not encounter one instance in which the district administration prevailed upon the power producer to either compensate for disruptions to these irrigation systems or reduce water diversion to provide adequate water supply.[6]

Seeing the futility of seeking redress for damage or guaranteed minimum flows from already-constructed projects, farming communities in Kangra have started blocking construction of hydropower projects until the power developer agrees to binding conditions. One example of this concerns Ganetta Kuhl, which diverts water from the Baner stream and conveys it 22 kilometers to the cultivated lands of more than 500 households in 12 different villages. The diversion weir for a partially completed small hydropower plant is located upstream of the kuhl’s diversion point.[7] Farmers worried that the project’s water diversion would reduce the water available to them. When letters outlining farmers’ concerns sent to Prodigy Hydro Power, the deputy commissioner, and even to the chief minister by the panchayat pradhan and kuhl committee president did not produce results, the irrigators used the threat of opposition and civil disobedience to block further project construction (figure 3). As a result, project construction work was halted for many months. Finally, in 2013, the project developer agreed to the farmers’ demands, including that their water rights be guaranteed, and in return the farmers rescinded their threats; construction work on this project is currently underway.

The problems associated with project disruption of traditional irrigation systems are most pronounced in District Kangra due to the large number of kuhl irrigation systems. However, our research revealed that any location in the state in which kuhl diversion structures are located between a project’s trench weir and tail race were liable to experience water shortages during the year.

Chamba District – landslides, damaged watermills, and local activism

District Chamba lies to the north of District Kangra and contains the headwaters of the Ravi River and key tributaries, all of which have cut deeply into the Himalayan mountains. Because it lacks the broad arable plains that characterize the kuhl-irrigated Kangra Valley, farmers in Chamba combine rainfed cultivation on terraced fields carved into steep slopes with a high level of dependence on timber and non-timber forest resources, which meet both subsistence needs and generate revenue. The streams that flow from the forests down through the cultivated fields and villages to eventually join the Ravi River often power 10, 20, or more gharats (water-powered mills).

One of Chamba District’s defining characteristics is its steep topography. Not only are the roads carved, at times precariously, into steep mountain faces, but there are also numerous signs of natural and human-caused landslides. In some instances the failure of a terraced field has initiated a landslide whose head swale climbs higher upslope each monsoon season. In other cases road construction is clearly the culprit, especially where roads traverse steep, unstable slopes or cross ravines that may washout during monsoon storms.

In steep, geologically unstable terrain such as this, small hydropower projects trigger large landslides that not only cause extensive environmental damage but may also damage or destroy the project itself.[8] The Terailla Project is a case in point. Located beyond the small town of Tissa in a remote area of Chamba District, this is one of four small hydropower projects that take turns diverting and returning the Terailla River’s water in quick succession. The power channel of the Terailla Project is carved from a steep, unstable slope containing loose gravel and large rocks and boulders. After the project was commissioned in 2007, landslides destroyed large sections of the power channel. Car-size boulders slid downslope and deformed the one meter diameter pipe near the upper end of the power channel (figure 4). Two other landslides carried large sections of the concrete box power channel down the slope towards the source stream (figure 5). As of the summer of 2012 this power project had been nonoperational for one year due to the landslide damage.[9]

The upper edge of the growing landslide continues to move upslope and is now destroying the common grazing grounds of the adjacent village; if the rate of the slide’s uphill movement continues, then it will begin approaching the village itself. Additionally, project roads constructed across adjacent steep slopes to provide access to the diversion weir and to the power house have themselves triggered further landslides. Despite the clear potential for landslides in this area, the Detailed Project Report submitted by the power developer to HIMURJA states that there is no landslide risk in the project area. That this faulty assessment was accepted and the project approved suggests there are problems with the government review process.

The four tightly spaced small hydropower projects along the Terailla River have triggered numerous small and large landslides and wrought negative environmental and livelihood impacts. These include damage to grazing land and cultivated areas, destruction of gharats and other landslide-related damage. The cumulative negative effects of these projects have generated significant local opposition. Local community members have protested on numerous occasions and filed multiple court cases against these projects. Some protesters, including local village women, have been arrested and detained overnight in jail. The close proximity of these projects along one stream reach raises concerns about the cumulative impacts of clustered small hydropower projects. This is especially troubling because the project review process contains no mechanism for assessing the cumulative impacts of multiple projects located along the same stream or river.

Damage to gharats from small hydropower projects occurs commonly in Chamba. Gharats are the most common method for grinding corn, wheat, and occasionally rice. In exchange for grinding neighbors’ grain, the gharat owner usually receives 10% of the volume of grain they grind. These in-kind payments support the gharat owner’s family. Interestingly, in our surveys we found many examples of woman-owned and managed gharats; in most of these cases the woman was either a widow or the head of her household. Thus gharats are an important livelihood source for this otherwise disadvantaged group of people.

The 49 commissioned small hydropower projects in the state have stopped 104 gharats, either by destroying them due to land and rockslides or by diverting so much water that the gharat had to be abandoned due to lack of water (figures 6 and 7).[10] The elimination of these 104 gharats weakens the economic stability of the large number of households whose livelihoods they previously sustained. Although the Irrigation and Public Health Department No Objection Certificate directs the power developer to provide adequate water flows for gharats, the policy contains no requirement that compensation be paid gharat owners if the project damages their gharat or restricts the water available for diversion. This gap in the hydropower policy, which stems from urban policy makers’ general dismissal and undervaluation of gharats’ importance, suggests why the owners of many of these gharats received no compensation.[11]

Seeing the pattern of uncompensated damage, gharat owners in one stream in Chamba decided on a proactive strategy. For six months, using threats of direct action against a newly-commissioned small hydropower project, the owners of 12 project-affected gharats stopped the power project from operating until an acceptable compensation agreement was successfully negotiated. Eventually, through negotiations between the gharat owners, the power developer and the district commissioner, an agreement was reached that ensured acceptable levels of compensation for affected gharat owners. Based on the assumption that the gharat contributed the equivalent of a daily wage for the household (Rs 120), and the expected life of the power project (40 years), the negotiated settlement consisted of a series of five annual payments which together would total the equivalent of 40 years of daily wage labor. After the first payment had been made to the concerned gharat owners, they removed their opposition to the project and it began producing and selling electricity. However, as one gharat owner noted, if their payments cease, they will again stop the project through direct action.

The ability of these gharat owners to successfully engage in direct action and then negotiation reflects the pre-existing patterns of social activism and strong local governance traditions prevalent in Chamba. Local leaders, inspired by Gandhian ideologies of self-governance and sustainable local livelihoods, have worked to strengthen village panchayat institutions over the last two decades. This awareness building and social mobilization has centered on defending village community timber and non-timber forest product rights, advocating for community-based medicinal herb collection, and strengthening village level democratic institutions (Gaul 2001). The resulting awareness and knowledge concerning local rights and democratic process has empowered local communities to defend against livelihood threats, including threats from small hydropower projects.

Kullu District – threats to apple wealth, tourism

Kullu District’s fame, which extends throughout India and indeed the world, stems from a variety of characteristics that also influence the pattern of socio-economic and environmental consequences of small hydropower development. The district, located to the east of Districts Kangra and Chamba, tends to be relatively wealthy, in part due to the revenue from the cultivation of apples and stone fruit. Other key sources of local revenues include the film productions that regularly occur in the picturesque mountainous scenery, year-round tourism resulting from Kullu’s attraction to honeymooners and outdoor sports enthusiasts, and Kullu’s prominent pilgrimage destinations, which attract large numbers of pilgrims from throughout north India. The streams and rivers of Kullu District also support the largest number of private trout farms in the state as well as the Fisheries Department’s fish stocking program, which in turn attracts anglers from around the world and whose efforts are supported by the Himachal Angling Association. Lastly, parts of the district possess unique ecological and biodiversity values, which conservation efforts within the Forest Department, and especially the creation of the Great Himalaya National Park, seek to conserve and maintain.

The diverse elements of the economic foundations of the district – fruit cultivation, commercial film production, tourism, pilgrimage, fisheries opportunities, and conservation values – also heighten the stakes associated with the proliferation of hydropower projects. The cumulative impacts of the 11 completed small hydropower projects in the district (with many more under construction and planned) undermine the integrity and value of these elements.

The cumulative effects of transmission line infrastructure threaten the aesthetic and economic values of the Kullu landscape. As noted previously, private power developers are responsible for constructing power towers and installing transmission lines to convey the electricity they produce to the nearest HPSEB substation. This is a significant undertaking as the distance between power projects and substations ranges from 3 to 15 kilometers. When multiple power projects are located in one valley, each must separately construct transmission infrastructure; as the density of power projects increases, so does the resulting network of transmission lines spreading across the picturesque mountain landscape. Already this density has created negative effects. Residents we surveyed decried the ugly transmission lines that cut through the fruit orchards in the main Kullu Valley and also traverse the deodar forests and cultivated areas of the tributary watersheds of the Beas River. Many Kullu residents link the area’s natural beauty with the tourism and film industry and are worried about the negative effects on it of hydropower development. For example, a panchayat pradhan likened the white boulders of the dewatered reach of the Beas River to bleached bones and asked whether tourists would like to see those instead of clean, free running water. Regarding transmission lines, one local film production manager noted ruefully that the density of transmission lines in the valley has already disrupted shooting operations and is challenging the ability of film crews to obtain sequences not marred by transmission lines. Seeing the damage to apple orchards from transmission line construction and the fact that at least one person has died from electrocution from a low hanging power line, families that own land where towers need to be constructed are increasingly reluctant to sell the small plot of land necessary to construct the power tower.

Kullu District – threats to fisheries-based livelihoods

The negative effects of small hydropower development on water quality and fisheries-based livelihoods were also particularly evident in Kullu District. In addition to reducing the quantity of water available for kuhl irrigation systems and for gharats, as discussed above, small hydropower projects also affect water quality. Project managers clean desilting tanks by flushing the accumulated silt directly back into the source stream, thus creating a slug of sediment that harms downstream water quality and aquatic habitat and species.

These sediment slugs negatively affect downstream fisheries operations, both private and government. The Himachal Pradesh Fisheries Department’s oldest trout hatchery is located at Patlikuhl in Kullu Valley (figure 8). Established in 1909, the hatchery diverts water from the Sujan stream before it joins the Beas River. In 1988 a joint Indo-Norwegian effort was initiated to commercialize trout production (Sehgal 1999). The hatchery now operates independently of Norwegian support. In 2009-2010 it produced 3.75 lakhs of fish ova, 80 metric tons of fish feed (sold to local fish farmers and as far away as Sikkim, Bhutan, and Uttarakhand), and 12 metric tons of fish (Fisheries Department records 2012). This fish hatchery operation anchors the state’s fish stocking program and supplies fingerlings and other inputs to the growing number of households in Kullu that have established fish farming operations. The hatchery depends on clean, cold, oxygenated water to successfully manage the large number of tanks where fish eggs are fertilized and the ova are reared to become fingerlings or adults. Already, commissioned power projects (small and large) have increased sedimentation in the Sujan stream and more projects are planned. Hatchery managers are concerned about the threats to their source water posed by upstream hydropower development; they have written letters expressing this concern to the Director of the Fisheries Department.

When asked about the Fisheries Department’s ability to require water quality protection measures as a condition for approving the No Objection Certificate, the Fisheries Department official in charge of the Patlikuhl fish hatchery stated that initially department officers had attempted to restrict the proliferation of small hydropower projects due to their negative effects on fisheries and aquatic ecology. In some instances they had refused to provide a No Objection Certificate or they had required stringent water quality protection measures. However, the officer noted in a resigned manner that eventually they “had to give the NOC; it is the policy of the government” (to promote small hydropower).

Many local communities share the Fisheries Department’s concerns about the negative water quality impacts of small hydropower projects, especially given the recent growth of fish farming. The fingerlings and fish food from the Patlikuhl Fish Hatchery have enabled fish farming in Kullu District to grow rapidly from only four or five small private fish farms a few years ago to 52 farms. In 2011 these farms produced more than 50 metric tons of trout, which were sold to local and more distant markets at Rs 250-350 per kilogram and netted each of these 52 families approximately Rs 3 lakhs. This scale of economic production is significant. And, given the market and transportation linkages with large cities such as Chandigarh, Delhi, and even Mumbai, the potential demand for farmed trout far exceeds current production. However, the negative effects on water quality from hydropower development could significantly limit realization of this potential.

The potential threat small hydropower development poses for fish farming has strengthened local community opposition, which occasionally manifests as local panchayat refusal to grant the No Objection Certificate. One example of this concerns the controversy over small hydropower development planned for Haripur Nullah, a tributary of the Beas River on the east side of Kullu Valley. A project developer had been seeking the requisite NOCs from the three panchayats within whose boundaries the project fell. Concerned residents, including retired government officers and educators, had earlier formed a local organization (Jan Jagran Vikas Sanstha, JJVS) to successfully oppose a planned ski resort in their area (Asher 2008). This same group of individuals mobilized against the proposed small hydropower project, due to the anticipated damage to the private and government fish farms the stream supports and the negative effects on the four affected kuhls, the numerous gharats along Haripur Nullah, and the local government seed farm and private agricultural production in the project affected area. Due to this well organized local opposition, at eight different meetings the developer was unsuccessful in obtaining the NOC. Finally, just prior to a panchayat election (which the pradhan was not planning to contest) the developer, through a “miracle” (as recounted by JJVS members), managed to obtain a signed NOC from the pradhan. JJVS members rejected the validity of the NOC, which they claimed was obtained through undue influence, and sought redress through the district administration as well as the local courts.[12] Meanwhile, despite continued local opposition, the project developer has begun construction.

The intersections between fish, livelihoods, and small hydropower development extend to both sport fishing and subsistence fishing. Individuals that engage in subsistence fishing obtain cast net licenses from the Fisheries Department. In 2011 there were 350, 200, and 2000 cast net license holders in Districts Kullu, Chamba, and Kangra, respectively. The Fisheries Department estimates that in the state overall approximately 10000 households depend entirely or significantly on subsistence fishing for their livelihood. Sport fishing is also a significant and growing source of economic revenue, especially for those who operate fishing lodges and otherwise cater to sport fishers. In 2011 the Fisheries Department allocated 752 sport fishing licenses in Kullu District, the center of sport fishing for Himachal Pradesh. The Tirthan River, which flows out of the Great Himalaya National Park and travels approximately 16 kilometers before it joins with the Sainj and then the Beas Rivers, is one of the centers of sport trout fishing. The Himachal Angling Association, an active organization that promotes sport fishing, held its 2012 Trout Anglers Meet at Sai Ropa on the Tirthan River. The keynote address at the angling competition, given by the Association’s Secretary General, advanced strategies for strengthening “Angling Tourism” and denounced the negative impacts of small hydropower development on fisheries and the livelihoods they support.

The competition was attended by Mr. Dilaram Shabab, the retired MLA from this area who had spearheaded the successful effort to have the Tirthan River watershed declared off limits to small hydropower development (figure 9). Local panchayats, community members, and fishing lodge owners, with the able support and vision of Mr. Dilaram Shabab, as well as eventual backing from Fisheries Department, Forest Department and Great Himalayan National Park officials, launched a five year court battle against small hydropower development in this watershed. After three years of arguments and rulings in the Kullu District Court and more than one year in the High Court in Shimla, the High Court presiding judge ruled in favor of the arguments set forth concerning the negative effects on the environment, fisheries, and affected communities of the planned small hydropower projects in the watershed. The court declared the Tirthan off limits to all hydropower projects, and it cancelled the 9 previously approved small hydropower projects (Civil Writ Petition 1038 2006).[13] This is the only example in Himachal Pradesh of a watershed being declared permanently off limits to hydro development.

This concludes part one of this two part article. The second part will address labor issues related to small hydropower development and the functioning of the Local Area Development Authority (LADA). It will also discuss two promising institutional models for small hydropower development and offer a set of recommendations.

J. Mark Baker (JMark.Baker@humboldt.edu), Humboldt State University, Arcata, CA, USA

Please see Part II of this piece here: https://sandrp.wordpress.com/2014/06/11/the-socio-ecological-impacts-of-small-hydropower-projects-in-himachal-pradesh-part-2/

References:

Asher, Manshi (2008): “Impacts of the Proposed Himalayan Ski Village Project in Kullu, Himachal Pradesh – A Preliminary Fact Finding Report” (Himachal Pradesh: Him Niti and Jan Jagran Evan Vikas Samiti).

Baker, J Mark (2005): The Kuhls of Kangra: Community Managed Irrigation in the Western Himalaya (Delhi: Permanent Black).

Gaul, Karen K (2001): “On the Move: Shifting Strategies in Environmental Activism in Chamba District of Himachal Pradesh”, Himalaya, 21(2):70-78.

Government of Himachal Pradesh (2006): “Hydro Power Policy”, (Shimla).

Government of Himachal Pradesh (2012): “Memorandums of Understanding”, Himachal Pradesh Energy Development Agency (Himurja). Viewed on 25 May 2012. Website: (http://himurja.nic.in/moutilldate.html).

Payne, Adam (2010): “Rivers of Power, Forests of Beauty: Neo-Liberalism, Conservation and the Governmental Use of Terror in Struggles Over Natural Resources”, Columbia Undergraduate Journal of South Asian Studies, 2(1):61-92.

Sehgal, KL (1999): “Coldwater Fish and Fisheries in the Indian Himalayas: Culture” in T Petr (ed.), Fish and fisheries at higher altitudes: Asia. FAO Fisheries Technical Paper. No. 385. (Rome: FAOF).

Selvaraj, S and A Badola (2012): “Validation of the Small Hydro Power Project by Prodigy Hydro Power Private Limited”, (Neuilly Sur Seine, France: Bureau Veritas Certification).

Sinclair, John (2003): “Assessing the Impacts of Micro-Hydro Development in Kullu District, Himachal Pradesh, India”, Mountain Research and Development, 23(1):11-13.

END NOTES:

[1] The material presented here is partly excerpted from a recent article in Economic and Political Weekly, “Small Hydropower Development in Himachal Pradesh: an Analysis of Socioecological Effects,” vol XLIX no 21, pages 77-86.

[2] Run-of-the-river power small hydro projects divert water from a source stream or river through a dam or trench weir into a settling tank where the silt and sediment load settles to the bottom. From there the water is conveyed through a power channel (usually a large diameter pipe or concrete box tunnel) away from the source stream along a slight downhill gradient. The power channel length varies from one to as long as eight kilometers. From the power channel the water flows into the forebay and then passes into the steeply sloped penstock and then inside the power house where the force of the water is used to drive one or more turbines. The electricity the turbines produce is monitored and managed through a complex set of operating controls. Power lines one to fifteen kilometers in length convey the generated power to the nearest HP State Electricity Board substation, at which point the power joins the state’s power grid.

[3] The 49 commissioned power projects have a total generating capacity of about 200 MW, which represents about 20% of the small hydropower potential in the state. Some of these projects were commissioned prior to the 2006 Hydropower Policy. This article restricts its focus to small (5 MW or less, as defined by the Himachal Pradesh Power Policy) hydropower projects, which are often considered socially and environmentally benign. Large hydropower projects are also proliferating across the state, and have their own socio-ecological impacts. Sometimes small and large hydropower projects are located on the same stream or river; however, most of the commissioned small hydropower projects in Himachal Pradesh are located in different watercourses, and generally upstream, of medium and large hydropower projects.

[4] This rate of return assumes the power project operates at full capacity year round. However, even at half capacity, these projects still fetch a handsome return on investment, especially when central government subsidies are taken into account.

[5] A large kuhl may be defined as irrigating land in more than one village while a small kuhl irrigates land within one village.

[6] This is primarily due to the reluctance of power producers to allow water to flow across their diversion weir without capturing it and harnessing it to generate power and revenue. Farmers, especially subsistence farmers using traditional irrigation systems, generally do not have the political power and access to the district’s administrative machinery to force power producers to forego potential revenue in order to allow local traditions of water management to flourish. While some farmers in Sirmaur District resorted to the purchase of diesel pumpsets to lift water to irrigate cash crops (bell peppers, green beans and tomatoes), these efforts also failed due to the lack of water in the stream reach between the hydroproject’s diversion weir and tail race.

[7] Interestingly, and perhaps ironically, this same project received validation through a third party assessment under the Clean Development Mechanism of the Kyoto Protocol for producing Certified Emissions Reductions and satisfying the criteria for being a quality project (Selvaraj, S. et al. 2012).

[8] Indeed, the destructive landslides and other environmental degradation associated with this form of hydropower along the Alaknanda and Bhagirathi river basins resulted in the August 2013 Supreme Court stay on further hydropower development in neighboring Uttarakhand (Hon K S Radhakrishnan 2013).

[9] The Detailed Project Report for this project should have identified these landslide and slippage risks. In this case the report did not mention this risk. In the conclusion of the “Geological and Geotechnical Studies” chapter, the report notes that “on the basis of geological investigation carried out it is recommended that weir site, feeder channel, desilting tank, power channel, forebay, penstock and powerhouse sites are geologically suitable for construction. There is no major geological problem around the study area.” The next line notes that “there is no landslide zone.” Clearly this report, upon which approval was granted to the project developer to construct the project, contained inaccurate information about landslide risk. This raises the issue of how much review of the Detailed Project Reports Himurja officers should undertake. At least in this case, ground truthing could have avoided these severe and ongoing problems.

[10] In more than one instance, though the power developer told us that no gharats were located between the project’s diversion weir and tail race, site visits to the stream reach revealed this not to be true.

[11] Compensation rates for those gharat owners that did receive some form of compensation varied widely and seemed to depend on the relative bargaining power of gharat owners. Compensation ranged from monthly payments of Rs 3000 to lump sum payments of Rs 2 to 16.5 lakhs.

[12] The members of JJVS hypothesized that the pradhan had either been paid or coerced into authorizing the NOC, though there is no evidence to support this since there has been no investigation into this issue. Using monetary incentives to obtain the necessary no objection clearances is common practice. We heard many instances in which a No Objection Certificate was obtained from a panchayat for a payment of between Rs 30000 to 50000. As discussed above, NOCs must be obtained from a number of different government agencies, in addition to the project-affected panchayats. A general rule of thumb appears to be that obtaining NOCs from all the necessary entities usually costs approximately Rs 50 lakhs per megawatt of installed capacity.

[13] The court decision hinged on the anticipated negative effects of the projects on trout and other Tirthan River fisheries, anticipated local livelihood disruptions related to damage to gharats and kuhl irrigation, the fact that the projects would provide little local benefit (minimal local employment would be provided, electricity was not needed locally), and claims that the project documents lacked a real assessment of the burdens of the project on local communities. The proximity of the projects along the Tirthan River to the Great Himalaya National Park, with its populations of threatened Western Tragopan, Monal and other pheasants, Musk Deer and other species, also influenced the court’s judgment concerning the relative merits and demerits of these small hydropower projects (Payne 2010).

Related subsequent stories:

[14] http://www.indiawaterportal.org/articles/irrigation-systems-himachal-threatened-hydropower-projects

8th April 2014, 11 year old Radhika Gurung studying in standard fourth was accompanying her sisters Chandra and Maya along the river Teesta near Bardang, Sikkim. Suddenly, without having any time to respond, all three school girls were washed away by a forceful water released by upstream 510 MW Teesta V Hydropower project in Sikkim. While Maya and Chandra were lucky to be saved, Radhika was not so lucky. She lost her life. Residents here say that NHPC, the dam operator, does not sound any sirens or alarms while releasing water in the downstream for producing hydroelectricity and villagers live in constant fear of the river.[1] Residents demanded strict action against NHPC, but no action has been taken.

8th April 2014, 11 year old Radhika Gurung studying in standard fourth was accompanying her sisters Chandra and Maya along the river Teesta near Bardang, Sikkim. Suddenly, without having any time to respond, all three school girls were washed away by a forceful water released by upstream 510 MW Teesta V Hydropower project in Sikkim. While Maya and Chandra were lucky to be saved, Radhika was not so lucky. She lost her life. Residents here say that NHPC, the dam operator, does not sound any sirens or alarms while releasing water in the downstream for producing hydroelectricity and villagers live in constant fear of the river.[1] Residents demanded strict action against NHPC, but no action has been taken. nuary 2012, a family of seven people, including a child, drowned in the Cauvery River when water was released from the 30 MW Bhavani Kattalai Barrage-II (BKBII in Tamil Nadu). The same day, two youths were also swept off and drowned in the same river due to this release.[4] There are no reports of any responsibility fixed or any action taken against the Barrage authorities or Tangedco, although it was found that there was not even a siren installed to alert people in the downstream about water releases.[5]

nuary 2012, a family of seven people, including a child, drowned in the Cauvery River when water was released from the 30 MW Bhavani Kattalai Barrage-II (BKBII in Tamil Nadu). The same day, two youths were also swept off and drowned in the same river due to this release.[4] There are no reports of any responsibility fixed or any action taken against the Barrage authorities or Tangedco, although it was found that there was not even a siren installed to alert people in the downstream about water releases.[5] s of the Chalakudy River near the Athirappilly falls in Kerala and the Kadar tribes, which traditionally stay close to the river and are skilled fisher folk too, are fearful of entering the river.

s of the Chalakudy River near the Athirappilly falls in Kerala and the Kadar tribes, which traditionally stay close to the river and are skilled fisher folk too, are fearful of entering the river.

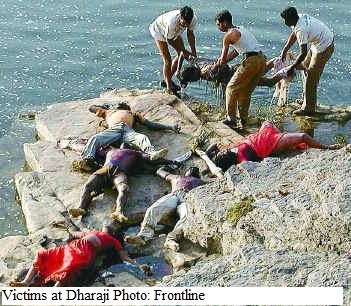

east 70 people were killed at Dharaji in Dewas district of Madhya Pradesh due to sudden release of huge quantity of water from the upstream Indira Sagar Dam on Narmada river. Principal Secretary Water Resources Madhya Pradesh inquired into the incident and found that “there was no coordination between agencies”[12]. No accountability was fixed and no one was held responsible. NHPC, who operated 1000 MW Indira Sagar Project, simply claimed that it was a case of miscommunication and that it was not aware of the religious mela in the downstream of the river. As SANDRP observed then, “ It just shows how far removed is the dam operator from the welfare of the people in Narmada as the fair annually gathers more than 100,000 people of the banks of the river. It is a scandal that no one was held responsible for the manmade flood which resulted in the mishap[13].”

east 70 people were killed at Dharaji in Dewas district of Madhya Pradesh due to sudden release of huge quantity of water from the upstream Indira Sagar Dam on Narmada river. Principal Secretary Water Resources Madhya Pradesh inquired into the incident and found that “there was no coordination between agencies”[12]. No accountability was fixed and no one was held responsible. NHPC, who operated 1000 MW Indira Sagar Project, simply claimed that it was a case of miscommunication and that it was not aware of the religious mela in the downstream of the river. As SANDRP observed then, “ It just shows how far removed is the dam operator from the welfare of the people in Narmada as the fair annually gathers more than 100,000 people of the banks of the river. It is a scandal that no one was held responsible for the manmade flood which resulted in the mishap[13].”