Guest Article: Steve Lockett, Mahseer Trust

(Above: Teesta-Mahananda Link Canal, part of a water-use strategy that seems broken. Copyright: Adrian Pinder, Mahseer Trust)

Rivers change course, it is part of their being. A river changing course can bring unexpected or unwanted ramifications. Sometimes they can be quite devastating. But when they come as a result of deliberate actions to alter the river’s course how can we expect people, whole communities or wildlife to cope?

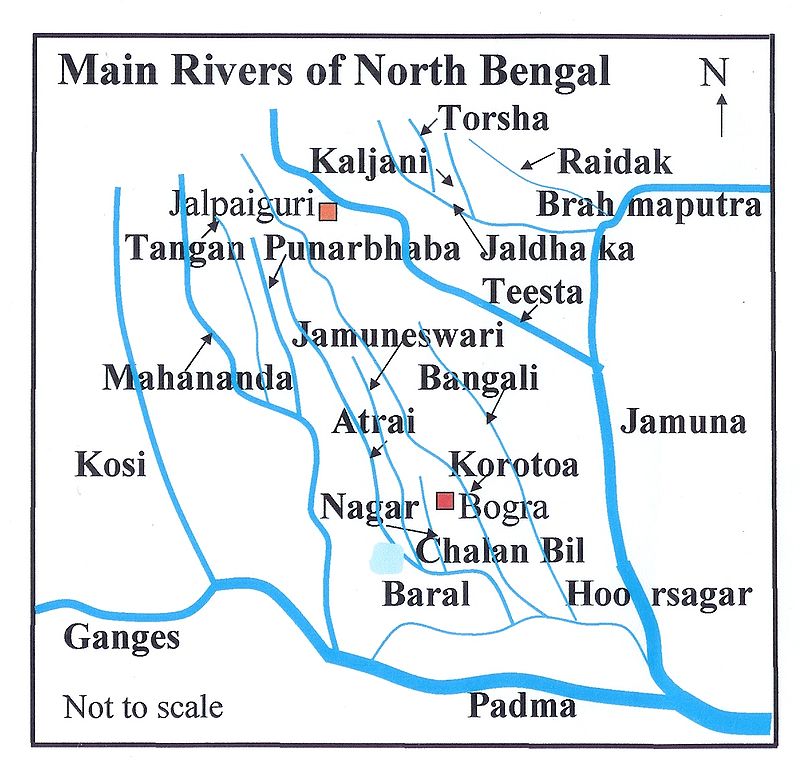

The Teesta river was previously a tributary of the Ganges then it shifted to join Brahmaputra in 1787. As with many rivers of the Ganges – Brahmaputra – Meghna basins, wholesale shifts are commonplace and to a large extent, people and wildlife have adapted to live with these hydrological movements. But when humans engineer rivers to force them to change course, expect them to bite back.

In fairly recent geological time, the rivers Teesta and Mahananda were connected through the Purnabhaba river. This patchwork of drainage has complex interactions as part of its very being. Whether they are tiny ecosystem interdependence, or larger events like the1879 Teesta floods, which even caused Brahmaputra itself to change course, these relationships give us a river as life force.

Our Mahseer Trust team were visiting a sensitive location in the sliver of land sandwiched between Nepal, Bhutan and Bangladesh. The West Bengal city of Siliguri was the site where in the 1820s Francis Buchanan-Hamilton found a new species of mahseer fish and called it Barbus tor after the local name turiya. Subsequent research has moved all of the large mahseers into their own genus, called Tor. This fish of Mahananda and Teesta rivers now gives its genus name to all of these mighty fish and this particular species is now called Tor tor.

LINK: We are doing article interlinking! For a more detailed look at the search for Tor tor, please read Adrian Pinder’s diary article here: https://www.mahseertrust.org/post/hunt-for-tor-tor

The hunt to re-describe Tor tor hinges upon finding fish from the wild in a landscape notorious for rivers changing course and humans making more intrusive changes.

“Heavy dependence on structural means to manage floods, together with the effects of such other structures as roads, highways and railroads that obstruct flow of water in some cases aggravate the flood situation.”[i]

Much is known about the history of river movements in this region, with references to scientific study from James Rennell’s surveys from 1764 to 1777[ii]. While these were quite crude studies in today’s standards, still “Their primary value lies in recording relative position or the importance of transient features like rivers and villages in respect to more permanent landmarks like hills and major towns.”[iii]

If these rivers do not flow to the sea, carrying land-forming sediment with them, natural coastal defences against the all-too-common cyclones are gradually wasted by erosion. Yet major engineering works to divert water between these two important rivers not only appears to be a net loss for river flows in the region, it may not even do the job for which it is supposed to be engineered.

Siliguri is the second largest city of West Bengal with huge water and waste disposal needs. Within the city itself, there are fears that encroachment on Mahananda will see it change course[iv]. The Mahseer Trust team – which included a Siliguri native and our main local coordinator who is from Kalimpong – scoured fish markets in the search for the target fish. Stories from the traders not only bemoaned the loss of fish but also how the whole river network has changed markedly in recent times.

While encroachment is a problem with potential ramifications in the city, the dams, diversions and river bed mining present a different scale of impact. The search for fish moved outside the city, both upstream and downstream. Fishers who work on the rivers were the next target in the quest to understand how hydrological changes have altered fish communities.

Local fishers believe that the reason the interlinking canal was built was to ensure more water is maintained in Teesta and not ‘lost’ to Bangladesh.

Sushan Mani Shakya, Mahseer Trust Lead Officer for Nepal accompanied the programme and was surprised by the reactions from locals. Coming from an upstream riparian country to visit India for the first time, he was very interested in matters of water sharing.

“It appears to me that due to Indian geopolitics, they are not releasing water to Bangladesh.” He said, “From our conversations, it seems that the idea is to store water in wetlands. This appears to be a bonus but actually lessens the opportunity for locals to fish for high value native fish like mahseer.”

Alien fish species now feature highly among catches, with common carp and even South American armoured catfish seen more regularly. For local fishers, a handful of tiny fish may be all they expect to catch.

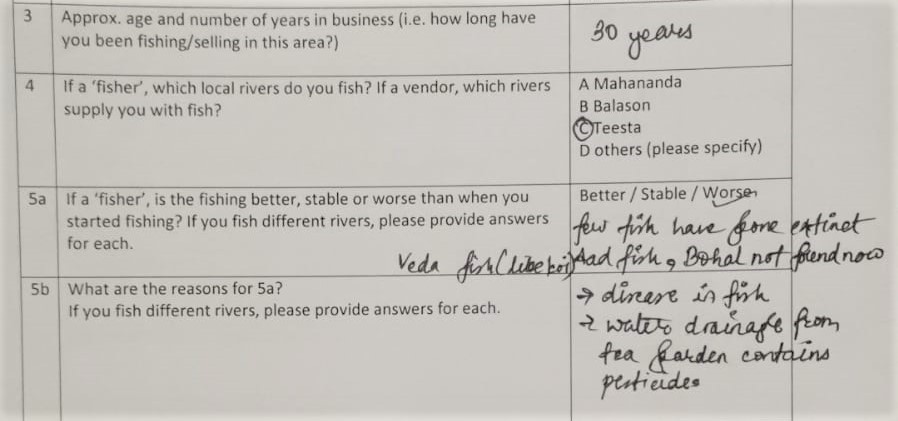

While carrying out sampling work, we instruct our teams to carry questionnaire surveys to help us understand the background to changes in local river habitat. By knowing more about how things have altered for fishing communities, we can better see what impact this will have had upon native fish species.

Among those interviewed on this trip, it was common to hear talk of falling catch rates and declining fish sizes. Often these are linked to increasing numbers being involved in fishing as a commercial activity thanks to ‘development’ drives by government departments following dam construction.

Several of the fishers who had been involved in fisheries in the days before the barrages came up said that while a reservoir appears to be an easier environment in which to fish, thus encouraging more people to try this line of work, it is much harder to catch significant quantities of fish compared to a natural river. Netting a river brings a better catch than attempting to net in a deep dam, they said.

Other commonly reported issues include the increased use of pesticides on upstream farms and tea estates; pollution impacts; introduction of exotic species; and local extinction of native species.

It has been reported for agriculture, as well, that the expected improvements in conditions for farmers from better access to irrigation water have not materialised[v]. Downstream loss of enriching sediment deposits and loss of groundwater are the main issues according to Mukherjee and Saha, with encroachment and land use change leading to general vegetation loss also a factor in local climatic changes.

The push to retain more water behind the barrages also leads to unexpected consequences like increased sedimentation in upstream areas due to lower flows. For some, this is a bonus, as there is more sand for mining even if there is less water for drinking.

Mahseer Trust local contact Shamip Chettri said: “Three sand miners died recently when the mine collapsed.” This is a common story across the country but there are suggestions that the West Bengal government seems to be cracking down[vi]. However, Sushan added: “Compared to Nepal the excavation we saw here is much more intensive, digging deeper and involves more people. We don’t see mining by hand on such a commercial scale in Nepal.”

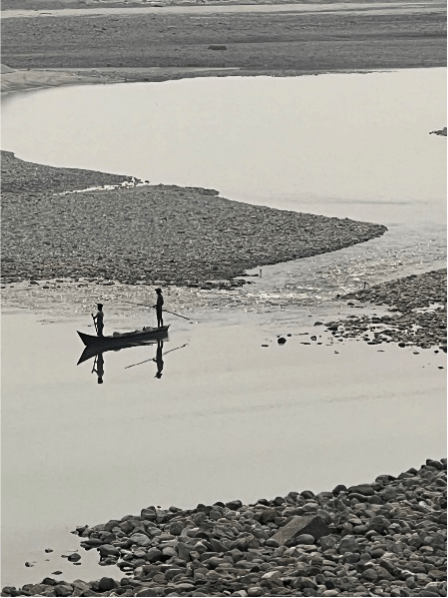

The sand “seems to be mainly used in local construction.” According to Shamip. Construction that places an even higher burden on already stretched infrastructure and removes yet more riparian and landscape vegetation cover. But for now, work has stopped by order of the state government and the Mahananda riverbed stands dry and forlorn.[vii]

“Water…has become both a political, diplomatic and environmental weapon”[viii]. This is water that is less available and should be shared between the riparian caretakers. Bandyopadhyay et al say that figures from1960 to 2011 show that overall discharge at Farakka barrage is falling. Dr. Kausik Ghosh, fluvial geographer of Vidyasagar University, interviewed in The Scroll in 2017[ix] said, with “high demand and declining supply” the “situation has gone from bad to worse.” our team also noticed areas which should be expanses of flowing water reduced to a few sparse channels. Dr Ghosh added: “one can notice vast stretch of dry land on the river just downstream of Gajaldoba barrage.”

The question remaining is: can we change course and help to support these two rivers to achieve healthier state? That these rivers are culturally important gives hope that locals will act on their behalf. Links between rivers and local legend are not hard to find[x] as is the case with many rivers in India.

Even boundaries between regions, states or countries can be affected by the movement of rivers. There are multiple issues facing these two rivers, which present multiple challenges to those who need them. Luckily there are many bodies now actively engaged in support for the ‘rights of rivers’ as well as pushing transboundary initiatives.

For our research programme, access to wild, natural fish populations are required. Just as with people, those fish and the array of associated freshwater wildlife that supports them need us to change course and allow rivers to continue on their courses.

Steve Lockett (steve@mahseertrust.org)

References:

[i] https://en.banglapedia.org/index.php/Flood

[ii] University of Michigan, 2023. Rennell’s Maps https://apps.lib.umich.edu/online-exhibits/exhibits/show/india-maps/rennell

[iii] Discussion: ʻChanging river courses in the western part of the Ganga–Brahmaputra delta’ by Kalyan Rudra (2014), Geomorphology, 227, 87–100. Sunando Bandyopadhyay, Sayantan Das, Nabendu Sekhar Kar. 2015.

[iv] https://www.thestatesman.com/bengal/tribunal-seeks-mahananda-status-report-1502983459.html

[v] Teesta Barrage Project – A Brief Review of Unattained Goals and Associated Changes, International Journal of Science and Research (IJSR) Volume 5, Issue 5, May 2016. Baishali Mukherjee and Ujwal Deep Saha. 2016.

[vi] https://siliguritimes.com/sand-mafia-spotted-illegally-quarrying-on-mahananda-river-in-broad-daylight-flees-away-after-seeing-the-cops/?__cf_chl_tk=cs.CBLfMBBUq3rinLch0zm9Cb7dE350ohEB4kjb8Ejs-1682505878-0-gaNycGzNDFA

[vii] https://www.telegraphindia.com/west-bengal/siliguri-cops-crack-down-on-illegal-mining/cid/1863039

[viii] https://www.orfonline.org/research/teesta-water-dispute/?amp

[ix] https://scroll.in/article/841244/why-teesta-runs-dry-incomplete-canal-network-and-climate-change-also-to-blame

[x] https://www.sikkimproject.org/the-story-of-teesta-and-rangeet/