Guest Article by Kundan Parmar & Satheesh Chothodi

(Feature image of Raneh Falls along Ken River by SANDRP)

Central India’s Upper Ken Basin, where the ancient Bundelkhand Craton meets the younger Vindhyan sedimentary rocks, appears at first glance to be a quiet and time-worn landscape. But new research reveals that the region is still being shaped by deep, hidden tectonic forces. In a recent study, geographers Kundan Parmar and Satheesh Chothodi used high-resolution elevation data and underground gravity measurements to decode the subtle fingerprints of active deformation imprinted onto the basin’s rivers and valleys. Their findings show that ancient faults, modern uplift and slow tilting continue to steer the paths of the Ken, Sonar and Bearma Rivers (all part of Ken Basin), creating steep drops, shifting channels and asymmetric basins.

To uncover this story, the researchers mapped 25 sub-basins of the Upper Ken Basin using 30-metre digital elevation data and Bouguer gravity maps (these are specialized geophysical maps that illustrate variations in the Earth’s gravity field after accounting for the gravitational effects of local topography) from the Geological Survey of India. We applied a suite of morphometric tools, essentially statistical indices that capture the shape and behaviour of river basins. These included the hypsometric integral (a quantitative topographical index used in geomorphology to summarize the shape of a drainage basin’s terrain and infer its stage of geomorphic development and susceptibility to erosion, which describes how eroded or “young” a landscape is), the stream-length gradient index (a geomorphological tool used to analyze changes in a river’s slope along its length, helping to identify areas of tectonic or landslide activity, used to pinpoint abrupt steepening or knickpoints (a sudden break in a river’s slope, such as a waterfall or series of rapids, that signifies a change in the river’s equilibrium profile) along river channels) and the Transverse Topographic Symmetry Index (a geomorphic parameter used to measure the asymmetry of a drainage basin, TTSI detects whether a basin is tilted in one direction). Together, these metrics acted like a detective kit for landscape evolution, revealing how the surface forms respond to hidden structures below.

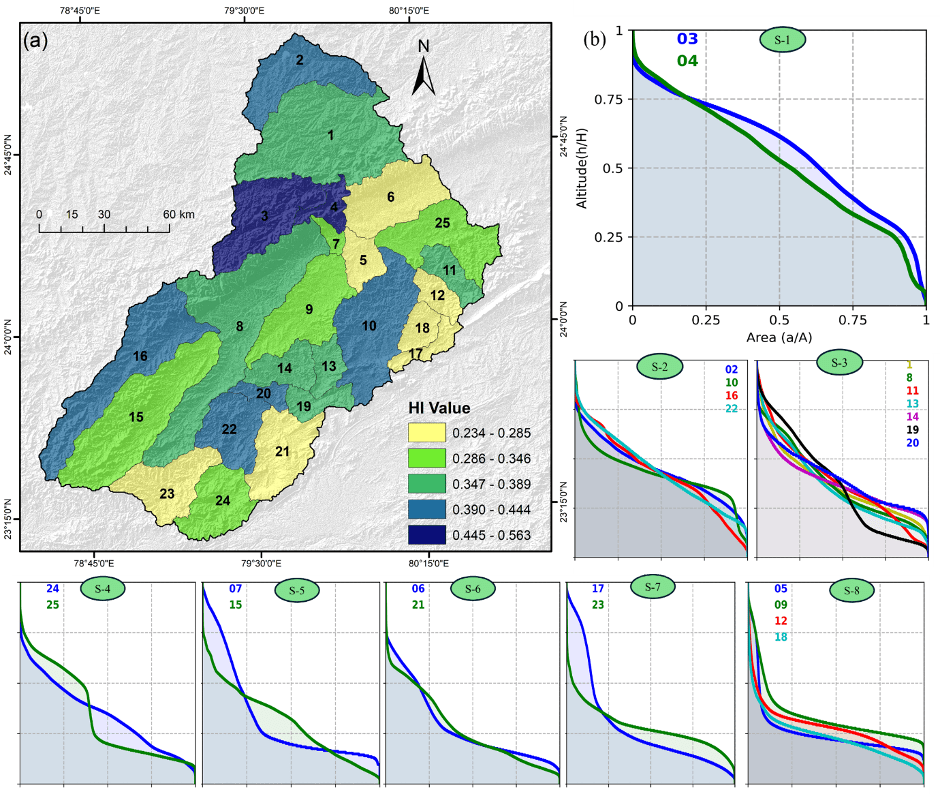

A key insight came from the hypsometric analysis, which reduces the elevation distribution of a basin to a single number between 0 and 1. High values—above about 0.6—indicate youthful terrain where uplift outpaces erosion, while low values, below 0.3, point to old, deeply incised valleys. Across the Upper Ken Basin, these values varied widely. Some catchments, labelled S-1 in the study (Figure 1), had high hypsometric integrals and convex profiles, pointing to uplifted, resistant blocks that rivers have not yet carved deeply into. Others, such as catchments S-6 to S-8 (Figure 1), had very low values and concave profiles, showing mature, eroded landscapes. These patterns were not random: when compared hypsometric values with the shapes of the elevation curves, the basins clustered by type. Uplifted blocks consistently showed youthful hypsometry, while subsiding blocks exhibited older, eroded signatures, strong evidence that tectonics, not just lithology (the study of the general physical characteristics of rocks), controls how much of the basin stands tall or sinks lower.

Fig 1: By Author, see for details: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geomorph.2025.110091

The story grew sharper through analysis of the stream-length (SL) gradient index, which flags knickpoints, sudden drops or rapids along a river profile. These features often form where the land is being pushed upward. In the Upper Ken, all three major rivers showed pronounced SL spikes, but the most dramatic appeared on the main Ken River about 141 kilometres from its source, where the SL value climbs to nearly 44,000. This unusual spike is associated with a major topographic break and corresponds with the location of well-known waterfalls such as Raneh Falls. Crucially, this steepening aligns with a strong positive Bouguer gravity anomaly, indicating a dense crustal block rising beneath the river. The finding show that the Ken River’s two major tributaries—the Sonar and Bearma—also carry strong signs of tectonic activity. This means the whole basin is being affected, not just one river. On the Sonar River, a very large spike in the Stream-Length Gradient (SL) Index appears about 180 km from its source, reaching a value of around 35,000. In simple terms, this is a place where the river suddenly becomes much steeper and cuts down rapidly into the land. What makes this important is that the steepening matches a clear rise in gravity-based measures (HG and TG), which indicate a denser block of rock pushing upward from below. This tells us that the river is responding to tectonic uplift, even though the surface rocks here are soft sandstone and quartz.

The Bearma River shows a similar story. In its lower section, after about 100 km, the SL Index jumps to values above 22,000, again marking zones where the river suddenly becomes steeper. These spots line up with sharp changes in the residual gravity anomaly, which point to buried faults or changes in deep rock layers. Even though the area here is mostly made of soft, clay-rich materials that erode easily, the steepening cannot be explained by rock type alone. The evidence clearly shows that tectonic forces—such as the movement of deep fault blocks—are controlling these sharp changes in river slope. To confirm the cause, we ran statistical tests showing that when elevation is used here as a proxy for tectonic forcing, it explains much more of the SL variability than rock type. In short, the rivers are responding to crustal uplift (the upward vertical movement of the Earth’s lithosphere, driven by tectonic forces, among others), not just cutting through harder rock.

Another indicator of active deformation came from drainage asymmetry. If one side of a basin is rising, rivers tend to shift toward the opposite direction, creating a lopsided layout. we measured this using the TTSI, which compares a stream’s position relative to the basin’s centreline. Plotting these values on polar diagrams showed consistent directional trends. Most western and south-western catchments displayed south-eastward river migration, with an average direction of around 130 degrees, suggesting the entire region is tilting toward the Vindhyan syncline (a downward fold in rock layers, forming a trough-like shape where the youngest rocks are in the center of the fold). A few eastern catchments showed south-westward drift, likely influenced by local lithology. Overall, the drainage asymmetry lines up with known fault trends, including NE-SW lineaments (a linear feature on the earth’s surface, such as a fault) and N-S grabens (a sunken block of the Earth’s crust, a long and narrow valley or trough formed by a system of parallel faults where the inner block has dropped down relative to the blocks on either side, which are called horsts), strengthening the case that these structural features are controlling how rivers shift within their valleys.

To tie the whole picture together, we used Bouguer gravity maps, which reveal density contrasts beneath the surface. Dense, uplifted blocks appear as gravity highs, while lighter sedimentary zones show lows. The alignment between steep river segments and positive gravity anomalies proved striking. The major knickpoint on the Ken River, for instance, sits directly atop a gravity high. Other SL peaks also match gravity highs. This consistent spatial pairing points to crustal blocks being uplifted by the reactivation of the Son–Narmada North Fault (SNNF), a deep ENE–WSW structure that has experienced multiple phases of movement. The study interprets the SNNF as being reactivated in an oblique-reverse manner essentially tilting the entire block so that rivers migrate, steepen, or flatten depending on whether they cross an uplifted or subsiding segment. Gravity highs reveal these buried blocks even when fault traces are not visible at the surface.

When all the evidence is combined, a coherent picture emerges: the Upper Ken Basin is the site of ongoing neo-tectonic activity, not a relic of ancient processes frozen in time. The rivers lean south-eastward because the land is being subtly tilted in that direction. Steep knickpoints form where rivers cross rising crustal blocks. Hypsometric differences map out uplifted versus eroded zones. And gravity anomalies trace the hidden architecture of dense blocks and possible blind faults. Together, these signs show that the Son–Narmada lineament remains an active player in shaping this central Indian landscape.

Beyond the scientific implications, the findings have important practical consequences. If rivers in the Upper Ken Basin are adjusting to ongoing uplift and tilting, water-resource planning must account for shifting channels, variable sediment loads and the possibility of long-term river migration. Dams or other infrastructure built along active or tilting blocks may face unanticipated stress, increased erosion, or rapid siltation. The reactivation of deep faults also raises questions about regional seismic hazards particularly in areas once assumed to be geologically stable.

Parmar and Chothodi’s study highlight how even subtle geomorphic changes can reveal the deeper forces at work beneath a landscape. By using accessible morphometric tools and pairing them with gravity data, the researchers show that the rivers of the Upper Ken Basin still carry the imprint of hidden tectonic movements. Their work adds to a growing understanding that intraplate regions, including parts of central India, remain tectonically dynamic. For planners, policymakers, and communities in the region, recognizing this evolving landscape will be key to preparing for a future shaped not only by rivers but by the deep Earth forces that guide their paths.

(Dr. Satheesh Chothodi (satheeshchothodi@gmail.com) is Assistant Professor, at Department of General and Applied Geography, School of Applied Sciences, Doctor Harisingh Gour Vishwavidyalaya (A Central University), Sagar, Madhya Pradesh)

Fascinating. Struck by how this alone should deter any consideration of nuclear power in private sector. Hard to imagine the dangers from large construction near rivers, given this. A friend ran into legal trouble recently while attempting to donate to an NGO a house his father had constructed on land purchased in 1962 in Tikamgarh — the extent of the land in the official records did not match records from satellite mapping. Ultimately, it was decided that with tectonic plate activity in the area, shifts had occurred in the intervening decades.

LikeLike